My First Downtime

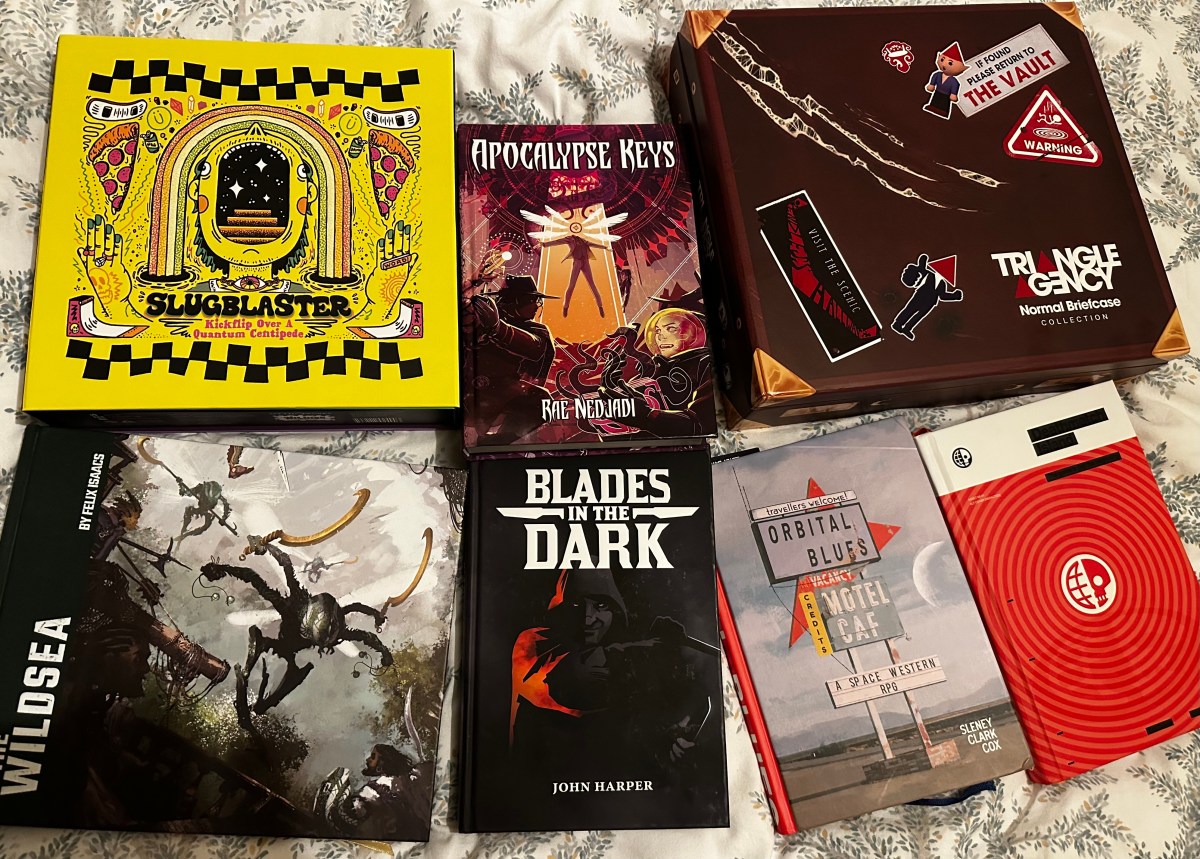

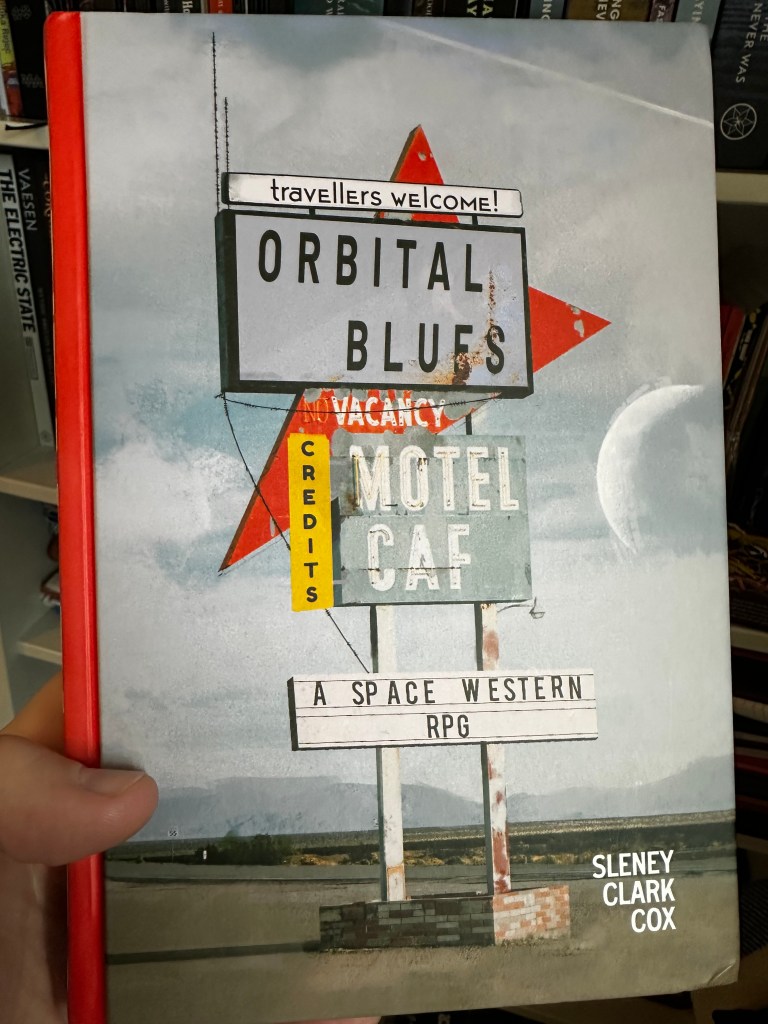

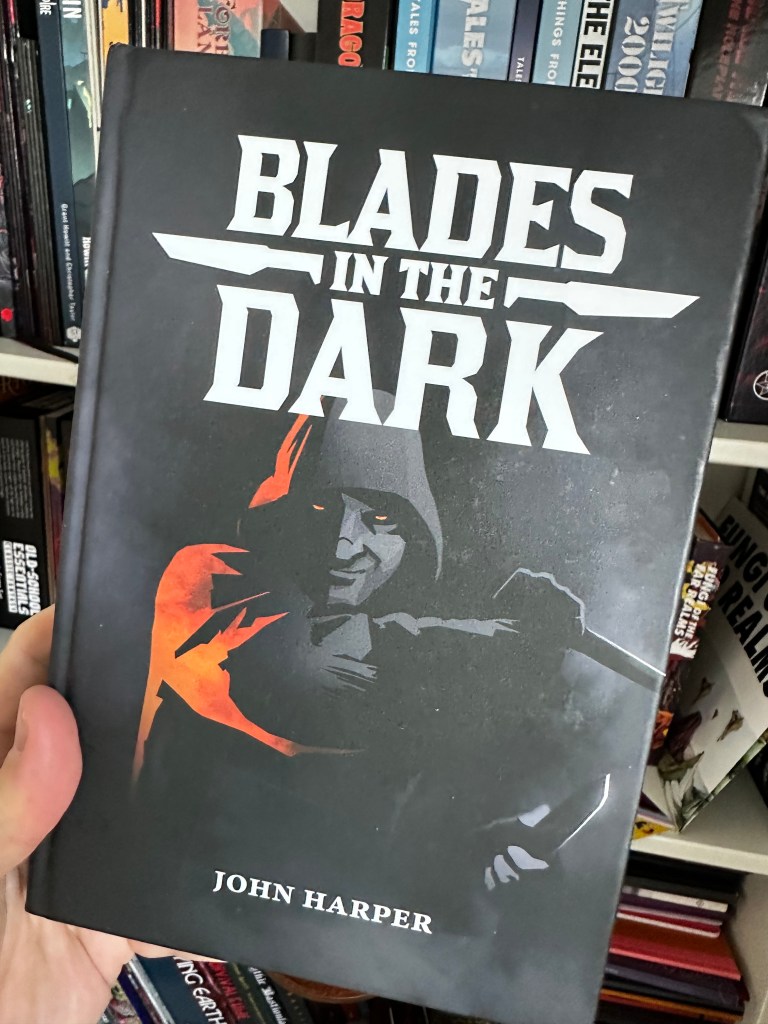

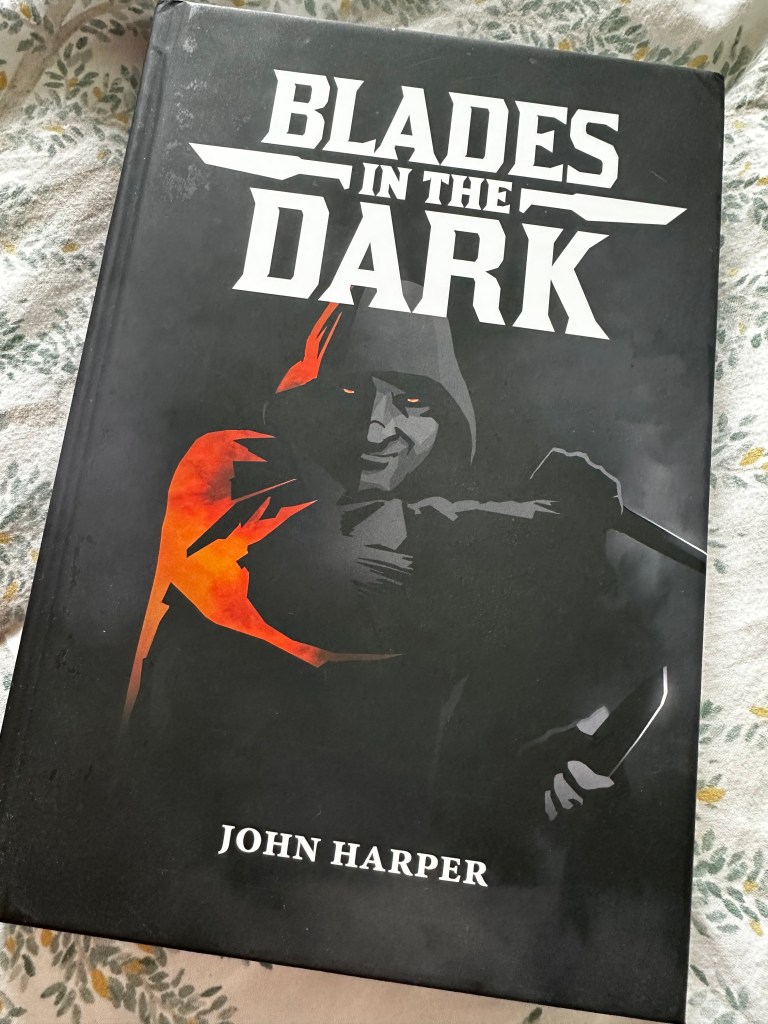

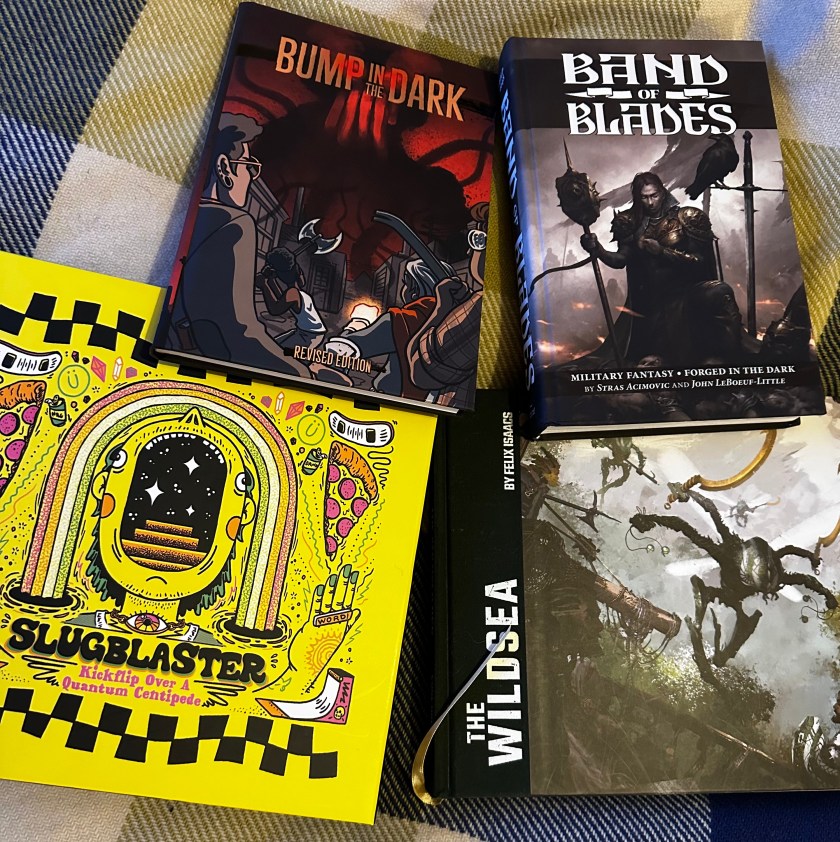

I’m taking a break from taking a break from Wednesday posts for this one. We had Session 2 of our Blades in the Dark campaign last week, and our first downtime. I also decided to start introducing a few elements from the latest Blades sourcebook, Deep Cuts, which came out earlier this year. So, I wanted to write about our experiences.

Deep Cuts Character Options

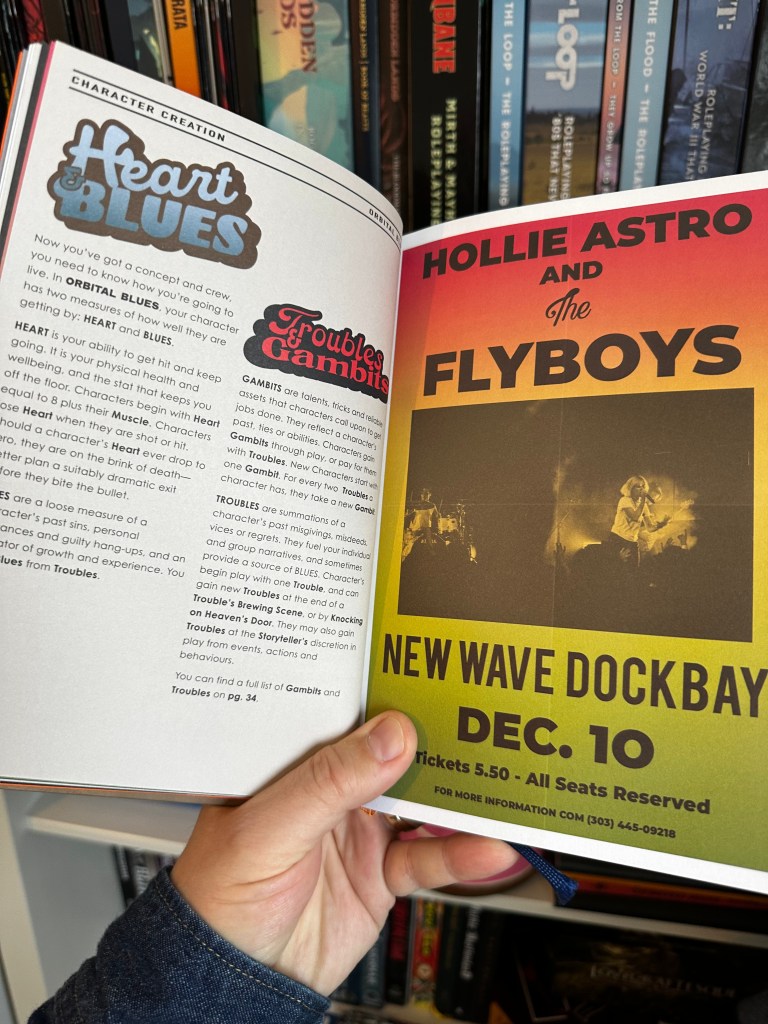

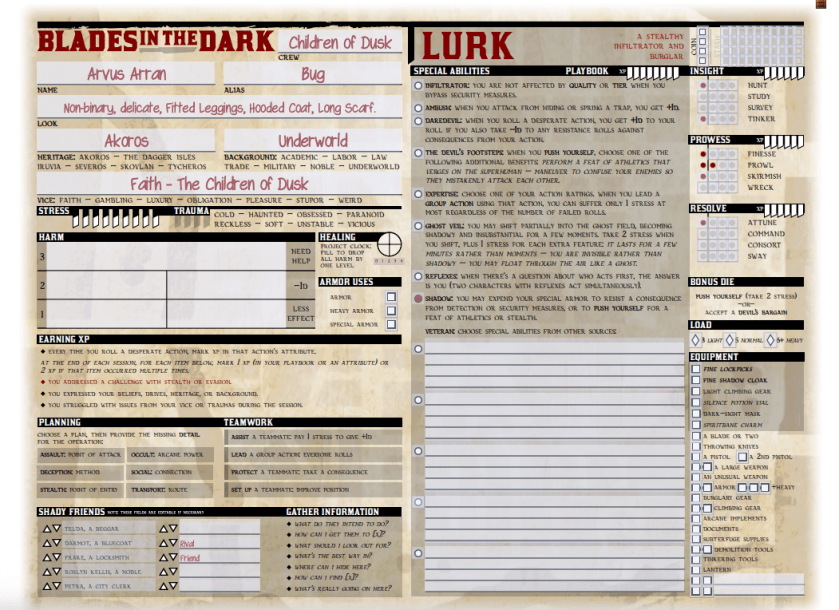

Deep Cuts really expands on the options for your new scoundrels. It doesn’t replace what’s available in Blades, it just adds depth. For instance, if your PC is Akorosi, maybe your family served among the clergy for the Church of Ecstasy. If your scoundrel had a military background, maybe they were a Rifle Scout, serving in the Deathlands and harassing “enemies with sniper attacks.” Before we got into the session proper, I offered all of the players to not only select from these new options, but also to reassign any of the Action dots they had assigned to reflect their Heritages or Backgrounds. What I discovered was most of them had already formed a pretty solid image of their characters in their heads. Even the one player who did take me up on my offer, only took the two examples I laid out above for their Hound because they fit the picture they had imagined so well.

I’m still quite fond of a lot of these new Heritage and Background options. They might have been a lot more useful if I had offered them from the start.

Downtime by the Book

In Blades in the Dark, John Harper tells us there are two main purposes to having a separate downtime phase:

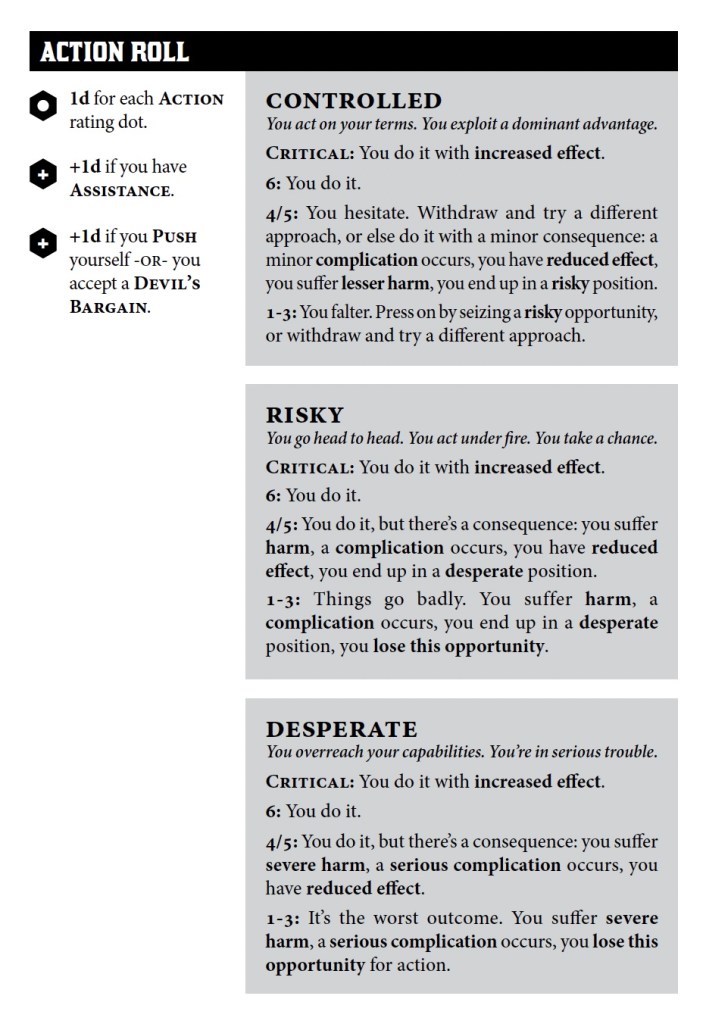

- The first is that the players could do with a little break after the action of the score that just went down. To be honest, this one doesn’t ring very true for me, but that’s probably because it’s been six IRL weeks since the last session and the crew’s first score. I also get the impression that, once you get the hang of this game, you’re sometimes running a score and downtime in the one session, rather than a score session followed by a downtime session. If that were the case, I can see the advantage of breaking the action up.

- Second, moving into downtime is a sign to all that we are changing the mechanics that will be needed in the game. To me, this seems like the more concrete of the two purposes. Blades in the Dark has tools for you to use during a score, and only during a score, and it has tools you only pull out during downtime. We don’t need to worry about divvying up the proceeds, dealing with the heat you’ve brought down on yourself or figuring out your long-term crew goals while you’re beating in some poor Red Sash’s head. Let that wait until you’ve got time and space for it.

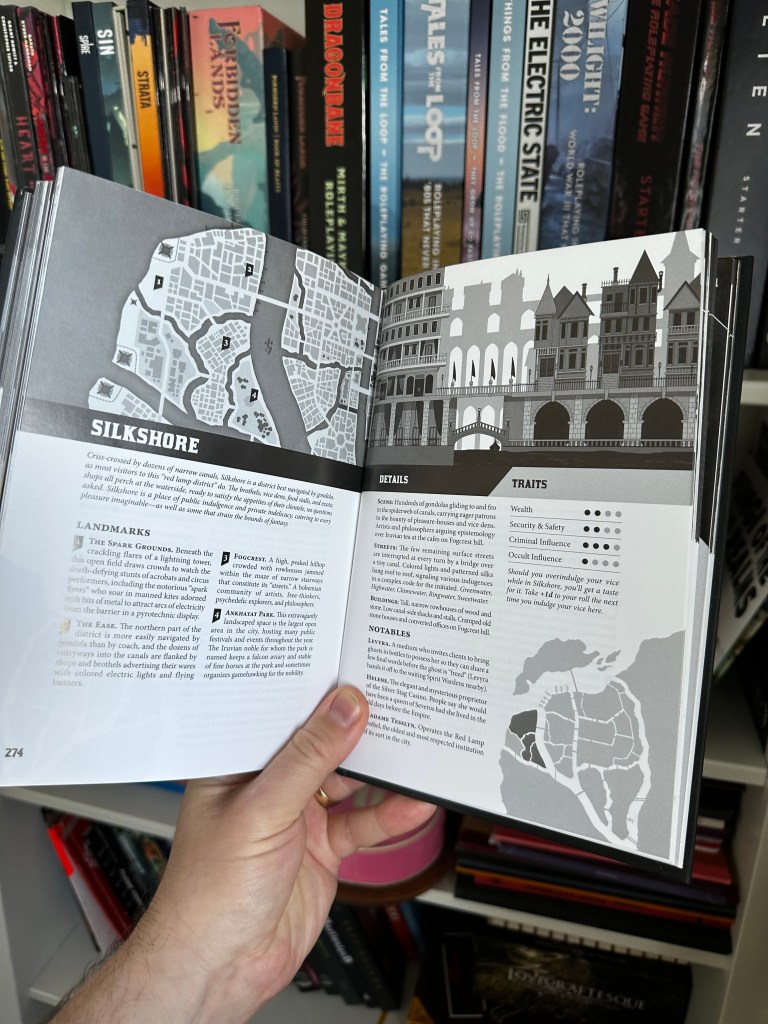

Luckily for me, it’s easy to follow along with the Downtime chapter of BitD. Once again, I have to praise the usefulness and usability of the book. The layout of the chapter leads you by the hand through the phase, from one step to the next. Three of my players have taken responsibility for maintaining the various crew/campaign tracker/factions sheets without my even suggesting it so that made the job even easier.

Payoff was easy enough, just a simple matter of recording the Rep the Death Knells got and dividing up the 6 Coin they garnered from the last score. They took one each, popped one in the crew stash and paid their tithe to Lyssa, the new leader of the Crows, as their patron. I ran this moment as a scene. I don’t think I would have if it wasn’t for the fact that she was pissed off with them for raiding the Red Sashes’ drug dens on the Docks, and I wanted them to know. She also gave them the option to take a job to redeem themselves. The Hive have been a bit too active in Crow’s Foot for her liking. She wanted the Death Knells to do something about it.

I mentioned Deep Cuts earlier. New mechanics appear in the sourcebook for downtime. They make it diceless, and they would also definitely up the Coin our crew made from that score if we had been using them. In BitD, you are given a range from 2 Coin for a minor job to 10+ Coin for a major score. In Deep Cuts, the Coin the crew accrues is determined like this:

- Score – 1 Coin per PC, plus Coin equal to the target’s Tier x3.

- Seized Assets – 4-8 Coin for a vault of cash. Stolen items can be fenced for 1-8+ Coin, but you take Heat (see next page).

- Claims – Collect payment from crew claims like a Vice Den.

Like I indicated above, we used the standard downtime rules from Blade in the Dark in this session. Now that we’ve experienced that, I’ll put it to the players to see if we want to make the switch. If and when we do that, I’ll come back and examine the other downtime changes then.

It was fun calculating Heat for that score. I’ll admit, I didn’t warn them that killing people on scores really hikes up the Heat. They started off the whole thing by murdering a bouncer, of course. In fact, I didn’t really explain the concept of Heat to them beforehand at all. This meant that they went in hard, loud and chaotic. I actually think this was for the best. The game is built on building up consequences, after all, as well as narrating big, exciting action sequences. Anyway, they ended up with 6 Heat, which was fast approaching a Wanted level. That put the shits up them.

In the book, the Heat section also includes the Incarceration section, which seems logical to me, but I didn’t need to refer to it, so I’m skipping it here.

Of course, due to all that Heat, they had to roll on the worst of the three Entanglements tables. These represent all the potential impacts of contacts, acquaintances, enemies and authorities getting wind of what the crew have been up to. Entanglements range from Gang Trouble, which can be dealt with internally, to Arrest! If you get that, it’s going to cost you Coin, a crew member or the effort to escape capture. The Death Knells rolled up Interrogation so our Hound was caught on her own and dragged down to the station for some “enhanced” questioning. We played this out in a fun scene where she went out to get beer to celebrate their big score and got ambushed out behind the pub by Sergeant Klellan and his boys. She wisely Resisted the level 2 Harm and the additional Heat, without incurring a single point of stress! All the others could do when she finally turned up was wonder where their beer was…

So then, we spent a bit of time going through what’s possible during the downtime phase in our last session. This can all be a little overwhelming the first time you do it. It can also take quite a while to get through each player’s turn as you talk through the possibilities and they negotiate amongst themselves to see who will spend their activities on reducing Heat for the whole crew. Sometimes it’s obvious who should do what. If a character has some Harm, it’s probably a good idea for them to get some treatment and Recover. If another scoundrel is a bit stressed out, they should go and Indulge their Vices to help them relax, but training, long term projects and acquiring assets are all more subjective. The chances are, they’ll turn out to be useful to the whole crew in the future, but they don’t feel quite as immediate in their effect as clearing Heat.

Anyway, I was gratified to see the PCs did all of the six possible downtime activities at least once. They managed to clear practically all their Heat. The Leech did this by studying the movements of the Bluecoats around the district so they could avoid them. The Whisper took an inventive approach, by losing a bar-room brawl in the King’s Salty Knuckles tavern, thus proving that he couldn’t be part of a crew of Bravos!

Our Cutter decided to acquire an asset, an old and worn-out little boat for use on a future score, perhaps. The players ad-libbed a scene in which they ribbed him about the state of the thing. But, of course, it only needs to be used once.

We had another scene when the Whisper’s strange friend Flint turned up on his canal boat with some electroplasm. Our Whisper needed it to build himself a lightning hammer as a Long Term Project. From Flint he also learned about the Sparkrunners, a gang of rogue scientists who are out there boosting government tech. This is one of the new factions from Deep Cuts, which “sparked” my imagination.

Just before we wrapped up for the evening, our Hound decided to deal with all her stress by visiting her local Temple of the Church of Ecstasy. She prayed and prayed, she prayed to hard and too much. She over-indulged in her vice and something bad happened. The bouncer she killed on the last score decided to haunt her!

Other Actions

Of course other actions are possible during downtime too. They decided to visit the ghost who had given them such good info during their Information Gathering phase in the previous session, because he said he would help them more if they really fucked those Sashes up good. From him, they discovered that Lyssa was responsible for the death of Roric, whose leadership of the Crows she then usurped. She had been backed up by the Red Sashes who had killed out ghost friend. He told them to go to Mardin Gull in Tangletown for the skinny on what all that was about. This wasn’t a downtime activity or an entanglement or anything. It was just something they wanted to do.

I also introduced a few more Deep Cuts factions in a little news segment. They learned about the Sailors being press-ganged on the Docks, The Ironworks Labour-force pushing for unionisation, the arrival of the Imperial Airship, Covenant without her sister ship and the recent adoption of the new Unity calendar and maps. Any one of these could potentially lead the crew to their next score. Except, maybe for the calendar one, I suppose.

Conclusion

I was very happy to have left a full session aside for our first downtime. It needed it. In fact, I would say, we could have used even longer. They still haven’t decided on their next score. I will say, I am quite happy with how many potential score options I managed to sneak into the various scenes in the session. I was worried that I wouldn’t give them enough opportunities, but, in the end, they came up quite organically, much like the scenes themselves. These all proved to be fun and freeform, allowing us to dow some world-building and to introduce some fun new NPCs.

I’m now looking forward to the next session, and, hopefully, the Death Knells next score, the Big One.