Break Time

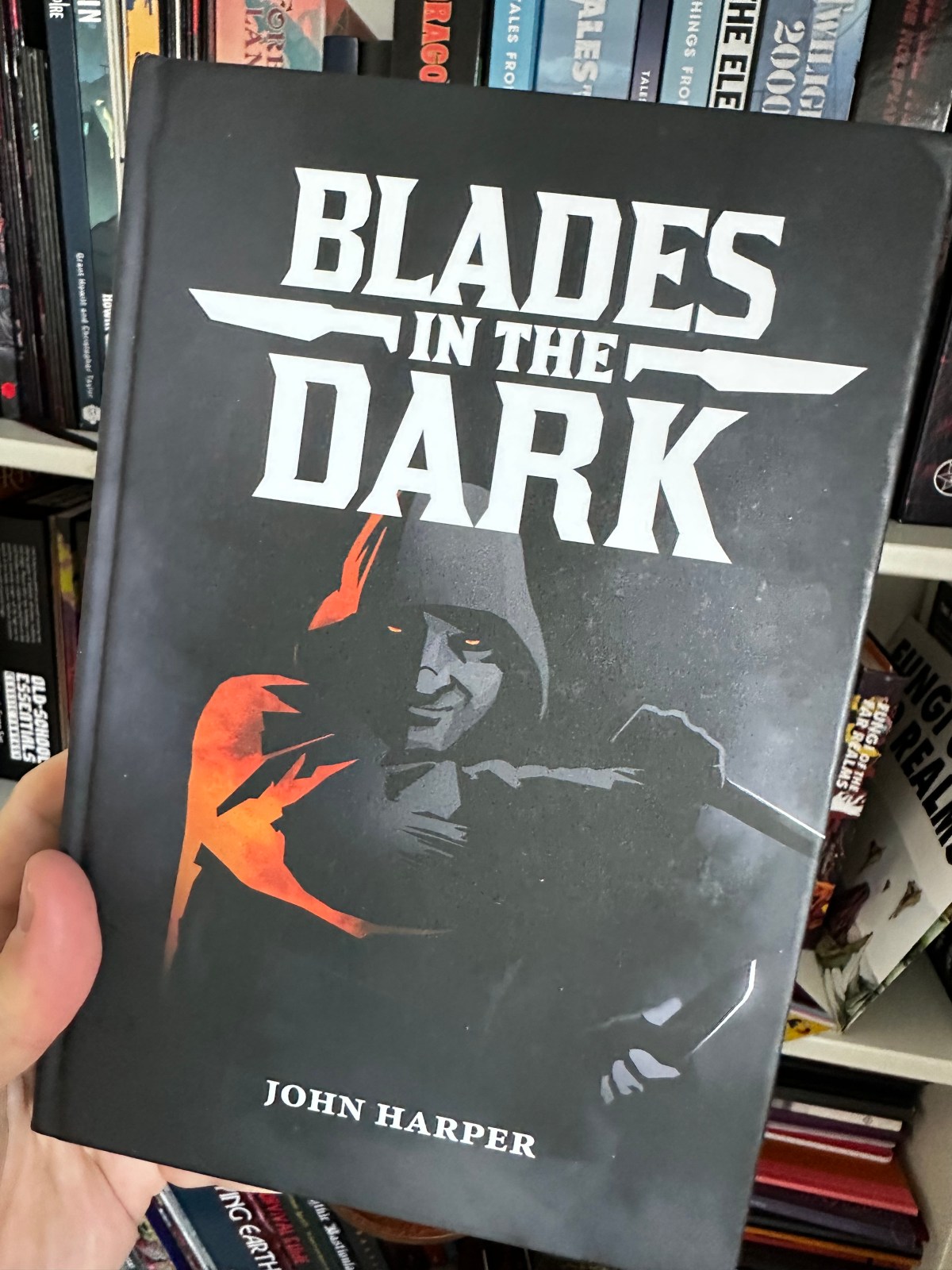

Our Blades in the Dark campaign is going well. We’ve only had three sessions but the players are moving the plot forward all on their own and are developing their characters in unusual and gratifying ways. But, for reasons, we’ve had to move our recent sessions to the weekend. So that has left us with a Wednesday gap. I grew bored of wasting my Wednesday evenings on housework, dog-walking and reading so I cooked up a plan to go back to Spire. But, since the change to our Blades schedule is only temporary, I wanted to make this a short one. To be certain we could wrap up our game, I decided to make it a one-shot. A city-break, if you will.

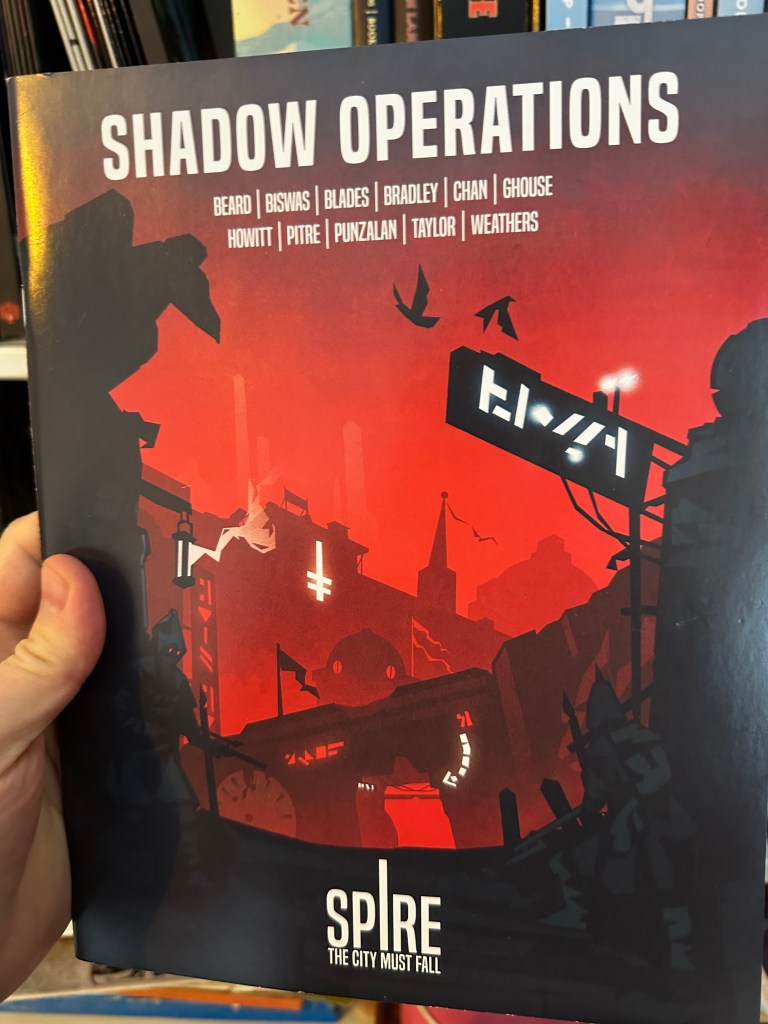

Shadow Operations

A few years ago, Rowan Rook and Decard published a book called Shadow Operations. It’s a collection of eleven scenarios meant to be played in a single sitting, and it’s great.

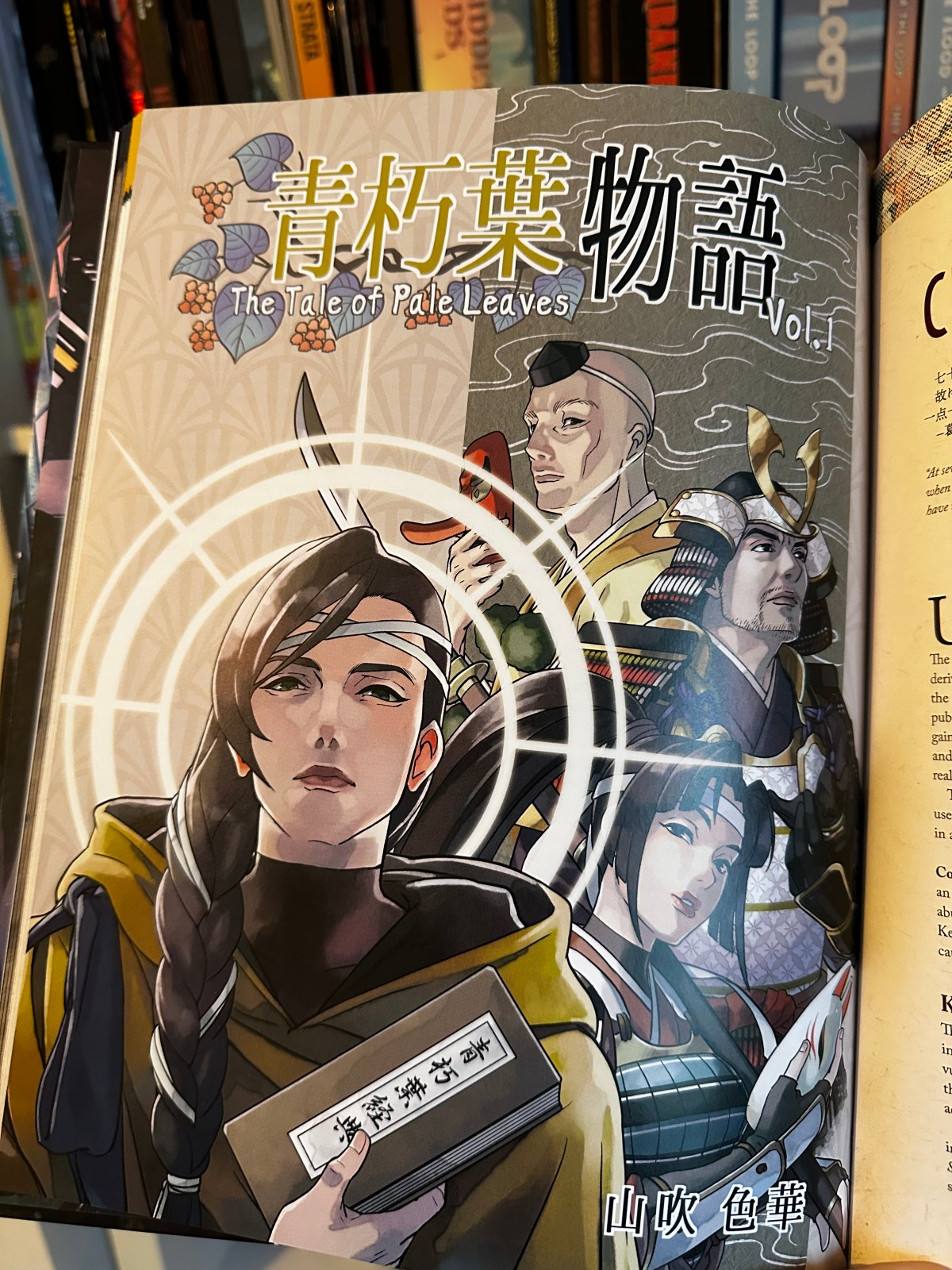

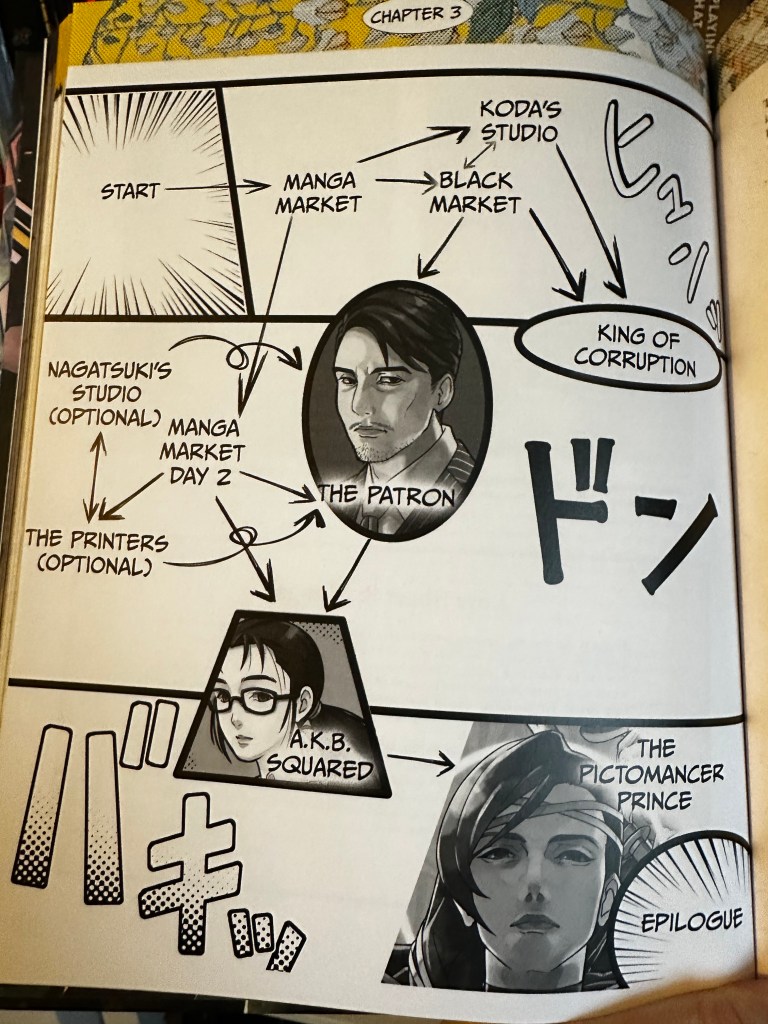

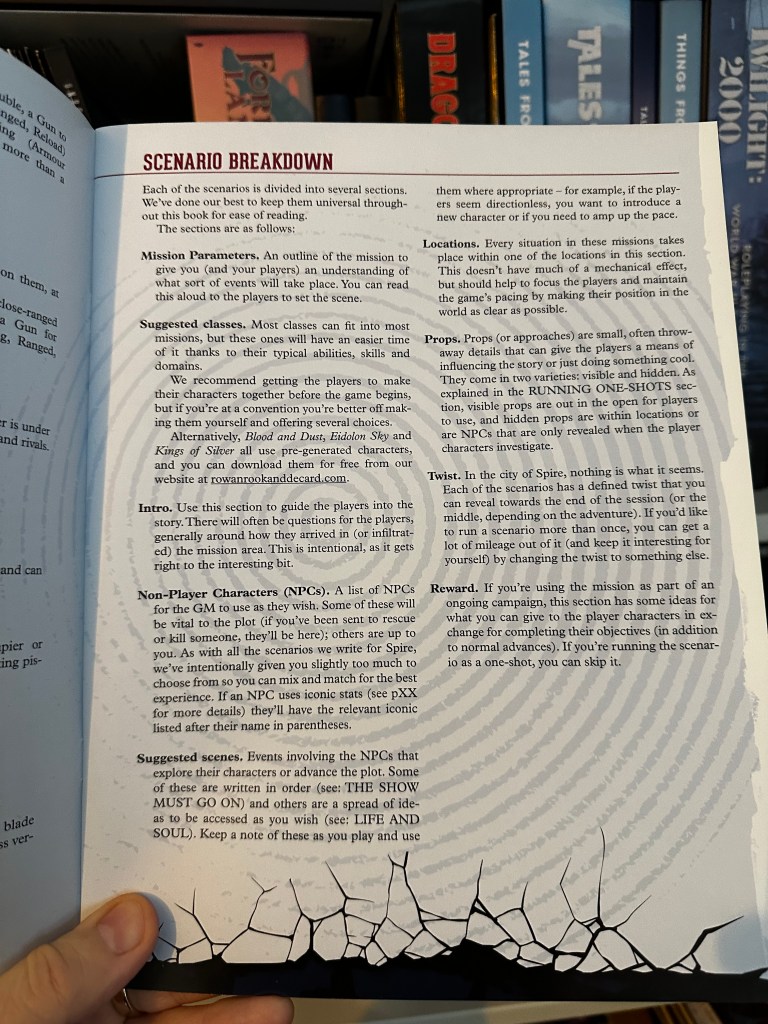

It does a couple of things cleverly and well. The first thing is that it presents a template for a Spire one-shot and then has every scenario in the book stick to it. Not only does this make the reading and digestion of the scenarios easy for the GM, it also provides them with the basis for creating their own one-shots. You can see this Scenario Breakdown in the image below.

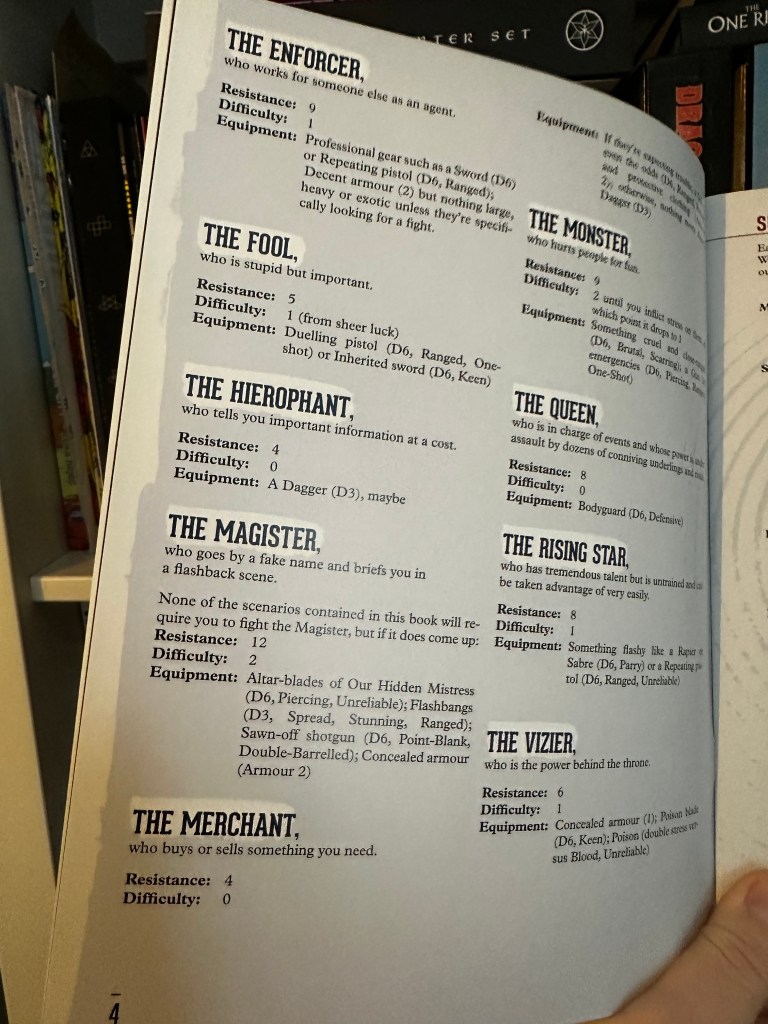

The other thing I really like about this book is the Iconic NPCs it provides. These are a list of statted out archetypes. They have titles such as “the Enforcer,” “the Queen,” and “the Vizier.” Then, throughout the book, each of the major NPCs presented in the scenarios fit into one of these archetypes. You don’t need stats for each NPC that way, you just use those iconic cookie cutters and refer to the handy reference page in the front if you need some stats for them. For a game like Spire, where there really isn’t anything like a bestiary or monster manual, and the enemies are just different types of people, this is a game changer. You can see the Iconic NPC stats in the image below.

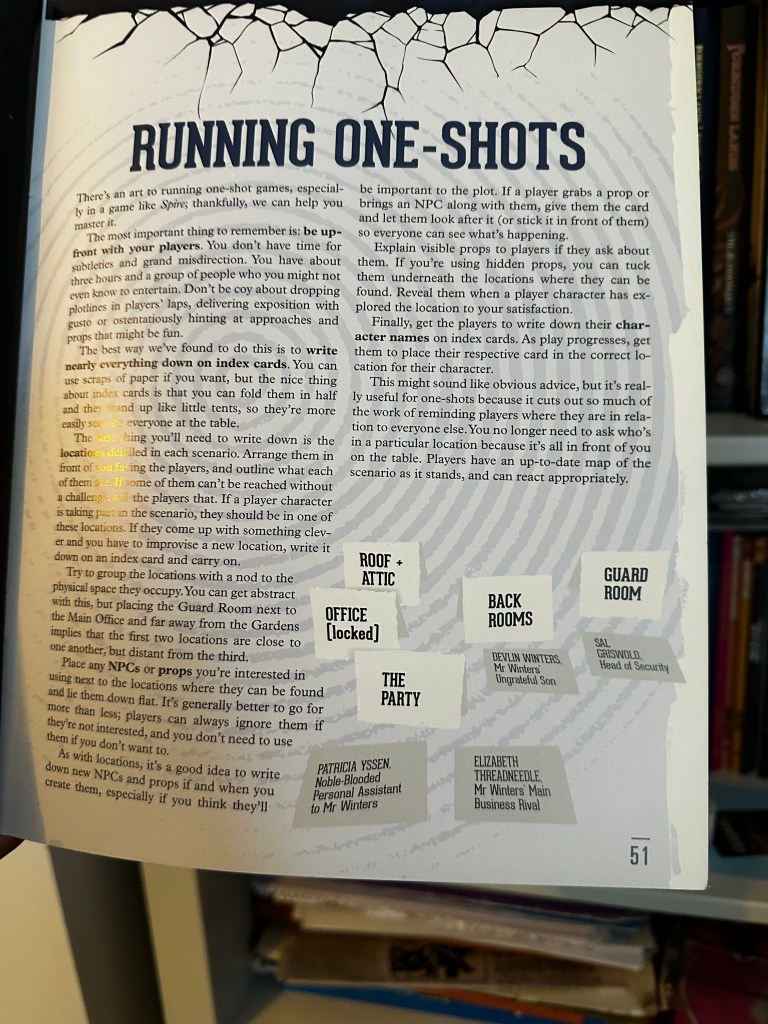

Other than these introductory sections, there is a page of advice on Running One-shots in the back. This is pretty bare-bones, to be honest. It does tell you its best to “be up-front with your players.” Which is a great advice. You won’t have time for hidden agendas, secrets and mysteries that require deep investigations to reveal. Just lay it all out for them or you will leave them frustrated and the scenario unfinished. I couldn’t agree with this more. But the main piece of advice is to use index cards to write down the various locations, NPCs, PCs and props on. Once you have done that, you can group them appropriately, kind of like a game of Cluedo (or Clue for my dear readers from across the Pond.) There is nothing wrong with this advice. As much as I could, I went with it, insofar as I could playing on Roll20. But, as it turned out, we never really used my virtual index cards. The players had no real problem remembering where their characters or any other NPCs were at any given time or where any particular location was in relation to any other. So, I can’t help but feel that this advice only scrapes the surface of what the prospective one-shot GM needs to know. So much better is the advice in Heart. In Heart we are told to pay particular attention to pacing, to start fast and keep the pace up as much as possible. A one-shot is a sprint, not a marathon. Provide necessary information in flashback or in summary and get the PCs started right in the middle of the action. Give them an achievable goal. I wrote a whole blogpost on this a while ago. You can check it out here. One thing I’ll say, however, is that much of the need for this advice is obviated by the structure of the scenarios in the book and the directions within each one on how, where and when to start, and what the PCs’ aim is.

Speaking of the individual scenarios, I found it quite tough to choose the one I wanted to run, especially as I only left myself about three days to decide on it and prepare it.

Here are a few that I considered:

- Life and Soul – Go kill Mr Winters, one of Spire’s most prominent gangsters, at his own birthday party

- The Last Train – Get aboard the Last Train travelling the Vermissian and steal it or the tech that powers it

- These Feral Saints – Find and recruit a newly reincarnated Hallow (drow saint) in Pilgrim’s Walk before some other cult does

But the one I went with was Jailbreak, a mission to infiltrate the Hive, Spire’s most notorious and terrifying prison, and, once there, ensure the aelfir can’t execute their prize prisoner, the Gnoll Warlord, Brakesh Gold-Tongue.

Jailbreak

There will be SPOILERS ahead, so, if you care about that sort of thing, look away now.

If you’re still here, welcome to the Hive. I’m going to discuss, briefly, my experience with Jailbreak as a scenario, playing Spire as a one-shot and whether or not I would recommend it.

I had four players for this one-shot and exactly three hours to complete it in. I like having time-constraints like this in some ways, as it gives me a very clear idea of how long I can spend in the various sections of the session. I was able to wrap it up within the time, although it was tight. We played online for convenience and because there was a gale-force wind and torrential rain that evening. We used Roll20, as I alluded to above. We found the Spire character sheets on that platform to be quite user-friendly and easy to navigate once you got used to them. It helps that Spire is a relatively rules-light game, certainly. There is a button you use to make rolls when necessary, which is handy as it combines your dice pool automatically. However, I will say that in instances where you have to apply a Difficulty to a roll you are forced to roll each d10 individually, because you can only see the highest die roll if you use the button. If an opponent has a Difficulty of 2, it means you have to take away your top two die rolls from the dice pool and go with the third highest. It’s a small thing but it did come a up a couple of times during play.

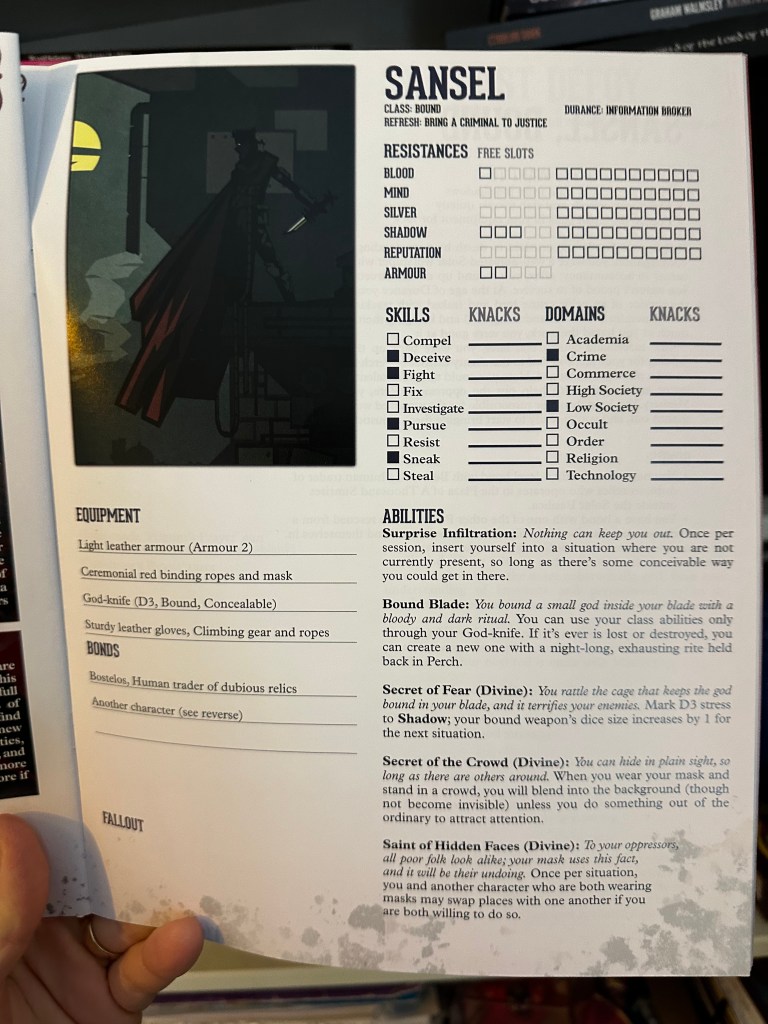

Suggested Classes

Another piece of advice that I feel should be central to running a one-shot of Spire, much like my advice for a Heart one-shot, is to make sure you have pregenerated PCs. When time is of the essence, you can’t be spending an hour creating a set of custom characters. One of the most useful parts of the scenario structure provided is the Suggested Classes. For Jailbreak, these were Bound, Carrion Priest, Lajhan, Midwife and Shadow Agent. So I stole and tweaked a number of pregens from other Spire products such as the Quickstart and the campaign frame, Eidolon Sky. The only one I had to create from scratch was the Shadow Agent as I couldn’t find one already made in any of the Spire books I own. The most time-consuming element of this was just copying and pasting a bunch of stuff into the Roll20 character sheets. But there is no doubt about how much time it saved on the night. I could have done a better job with some of the characters to be honest, but when they are only in the spotlight for such a short period of time, a long and complicated backstory can be a hindrance, actually.

Finally we get down to the scenario itself. As I mentioned above, the central goal is to infiltrate the Hive and get Brackesh Gold-Tongue out. But, the Intro actually asks you to start the PCs already inside the prison. You then just ask them how they managed it! I loved this as it got them started right in the action and removed all the time-consuming planning that such an undertaking would usually require. My players went straight in the front door in disguise, in a meat cart or as a sort of chaplain for the drow guards and prisoners.

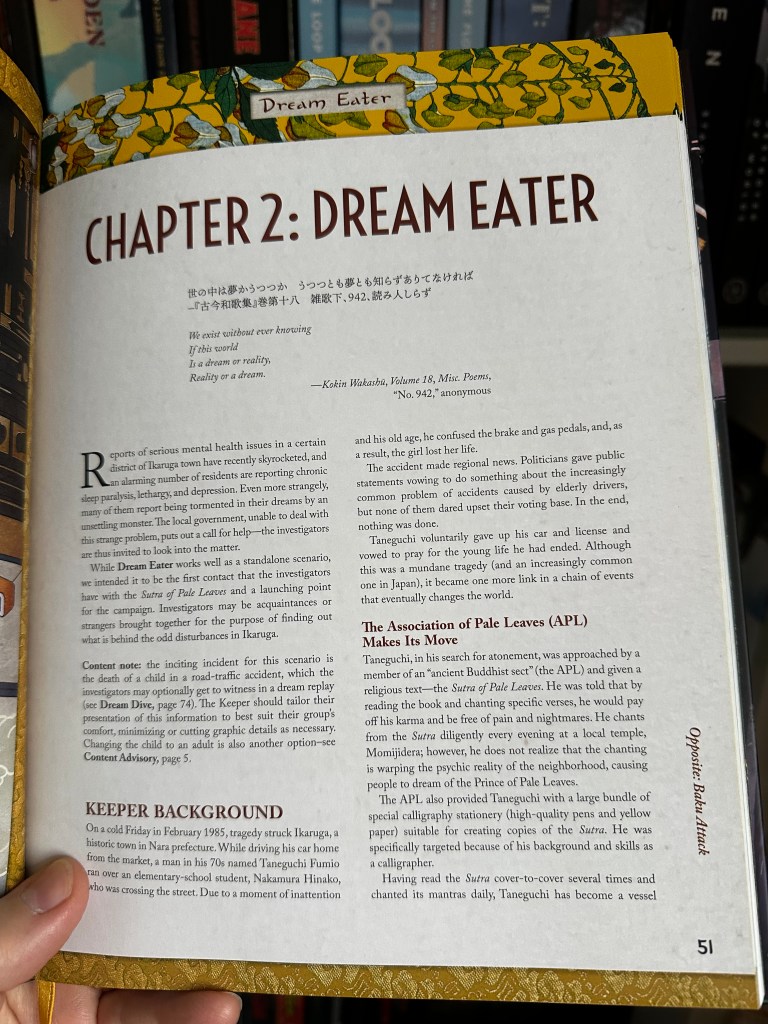

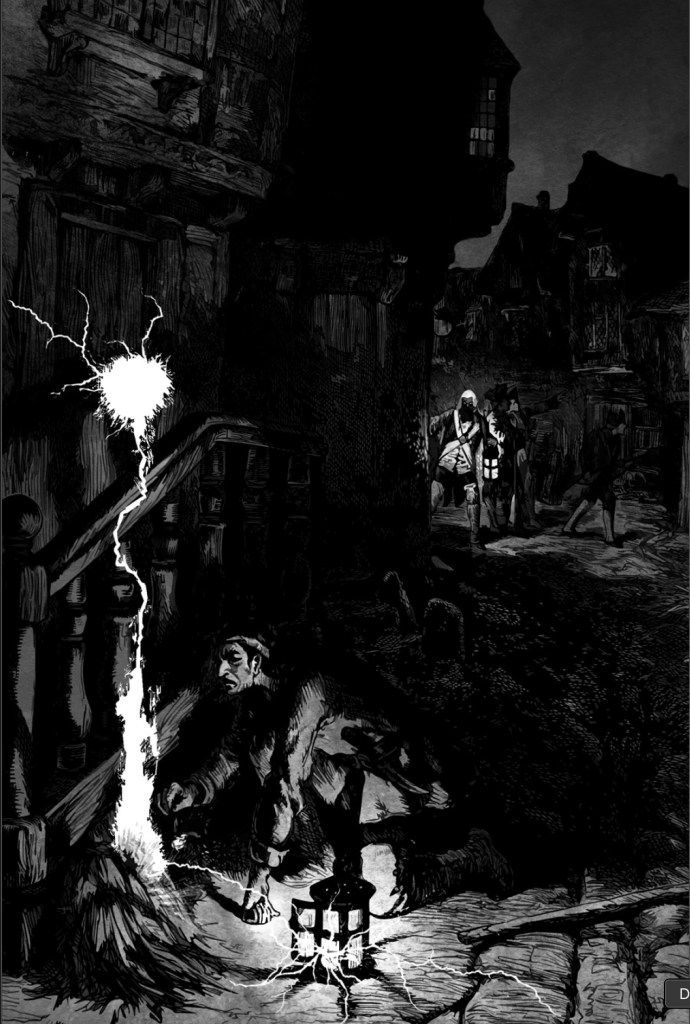

Intro

You are then asked to describe the Hive. Now, there is minimal description of the prison in the main Spire book. It introduces it as a jail built into the living walls of Spire itself. It has rows of hexagonal cells which can be dropped individually from the wall in the event of an escape attempt. The unfortunate inmate would fall inside their cell all the way through the central abyss of the city, possibly all the way down to the Heart beneath. This is a terrifying prospect but, as I said, the description of the building, its inmates and staff etc, is brief. I was happy I had a copy of Sin. That book contains a much more evocative section on the Hive that was written, as it so happens, by Basheer Ghouse, the author of Jailbreak. It provides juicy tidbits like the way there are lots of walkways spanning the chasm below the prison, but they don’t have any handholds. Gulp. It also provides some great examples of the types of poor mutated experiments of creatures that are resident in the Menagerie. The Menagerie a part of the Hive where the aelfir send their old pets, experiments and art projects when they’re done with them. One of the main NPCs in Jailbreak is Dawn-Upon-Ice, a hobbling former aelfir who now acts as an information broker of sorts and can produce all sorts of nasty poisons in her guts for a price.

NPCs

Speaking of NPCs, Jailbreak has five, which is an easily manageable number. I will say, we didn’t interact with all of them, we skipped Qadiv Love-Fool, a sort of gnoll collaborator, purely due to the fact that the PCs did not pursue the information they gained about him. Brakesh Gold-Tongue, himself and Dew-In-Shattered-Mountains, the aelfir poet-interrogator, were my favourite to play. Neither lasted long against the PCs.

Suggested Scenes

After the NPCs section, there’s the suggested scenes. With the sort of structure you’ve got in these scenarios, this is really useful. Essentially, all you’re given to work with is a starting situation. The PCs are expected to push everything on from there. The suggested scenes allow the GM to pepper their descriptions of the infiltrators’ journey through the prison with interesting moments and opportunities to introduce the major NPCs. Here’s an example of one that I found particularly useful:

Smiling Kas spots the characters as she escorts Dew about the Deep Cells. She asks precisely no questions and accepts any excuse or alibi, no matter how ridiculous. If the characters have not threatened her and seem new to the Hive, she warns them not to stay in the Deep Cells too long.

I made liberal use of these suggested scenes.

Locations and Props

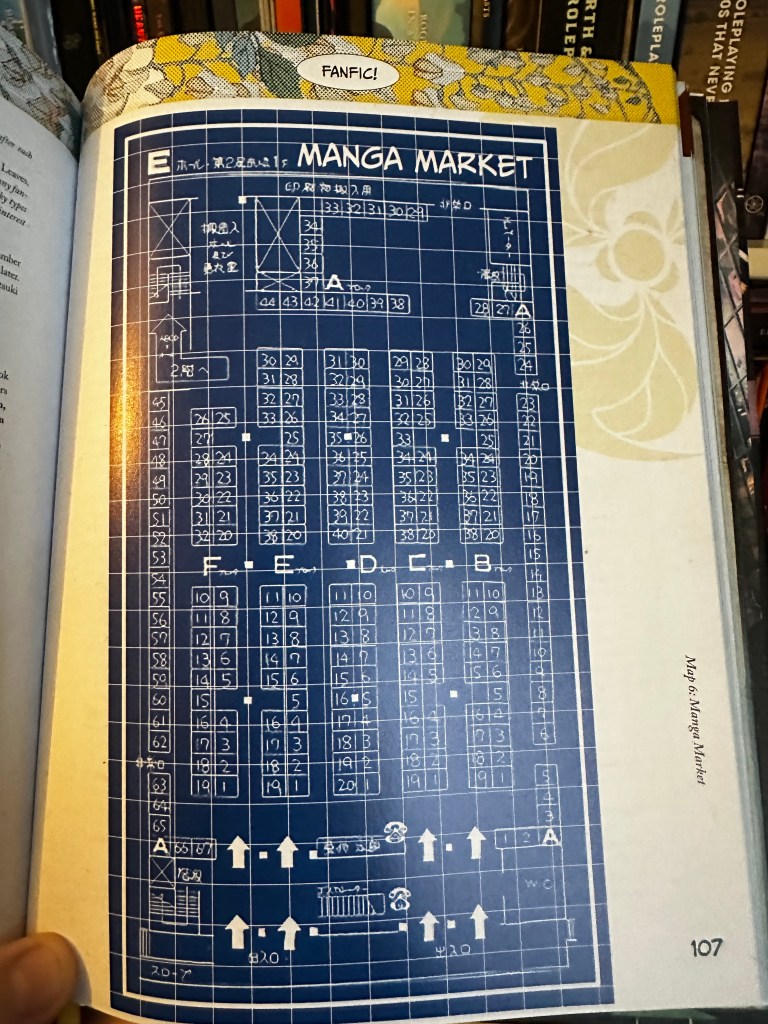

The next section describes the major Locations. I gave each one of these a little box drawn on the map on Roll20, thinking I would move the players’ tokens around from one to the next as their PCs moved. But, in practice, I didn’t really use them at all. Each of the Locations, which included the Menagerie, the Offices, the Guard Quarters, Watch Posts and The Deep Cells contain a brief description of the place, where it is in relation to at least one other place and the sorts of people and props that might be there. They are all short and to the point. Very easy to use on the fly. This section is supported by the prop section, which comes next. Props include unnamed NPCs like patrolling guards and menagerie experiments, by the way.

Twist

Each scenario has a Twist. Jailbreak’s twist is that Brakesh is a real asshole and has been going around the Hive murdering people, guards and prisoners alike. He was betrayed by his own side and left for dead before he was captured because he was kind of a psycho. He won’t leave with the PCs unless they either help him to kill each of the other named NPCs or offer him a shot at Snow-On-Stone, the aelfir commander who captured him. My players only encountered him about ten minutes before the end of the session. This worked out fine because their attempts to convince him to come with them failed so miserably that he attacked them and they were forced to kill him before escaping through an exploded front door to the prison. This worked out fine for them, as it happened. The Ministry wanted things to get messy to gain the attention of the papers and they were happy as long as the aelfir no longer had Brakesh as a source of information and didn’t get the opportunity to execute him publicly.

Conclusion

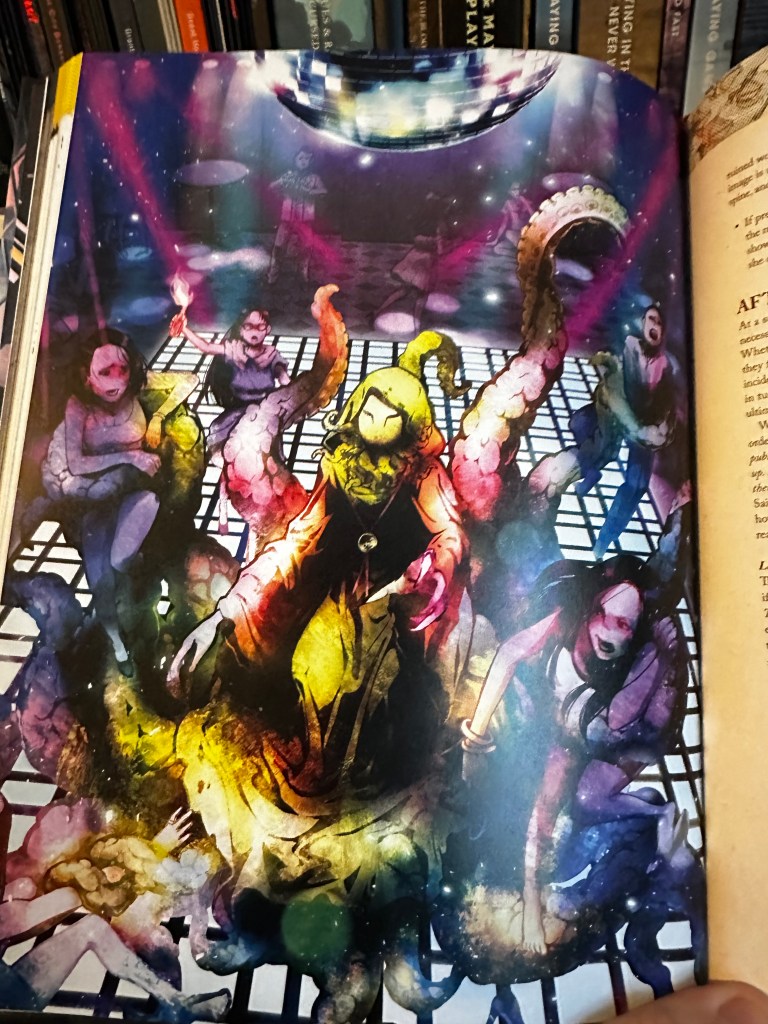

I love the way Shadow Operations is presented and it has a great variety of one-shot scenarios with an eclectic variety of settings and characters. Each of the scenarios is presented in only four pages, including one full page illustration. They are tight and easy to use because of the format. I do think it could do with some better advice on running a one-shot but, as I said above, if you follow the scenario structure, you’ll be alright.

Jailbreak was fun. It had a great setting. I loved describing a scene where the guards dropped one of the cells out of the wall and the PCs watched it plummet and the moment when they discovered one of Brakesh’s murder victims stuffed under the stairs was good too. But I found we had not enough time for the characters to shine as much as I would like. Maybe this is just one-shots in general, or maybe it’s how I handled it, but I would have liked a bit more room for the PCs’ characters to breathe.

I will definitely be going back to mine that rich seam of Shadow Operations in the future. It was so easy to pick up Jailbreak and run it with minimal prep. I would recommend it!