12 Months

It’s all over except the Stars and Wishes, dear reader, so I thought I’d look back at 2025 for my last post of the year. To help me achieve this, I’m going to utilise the twin wonders, data and spreadsheets. You can read other year end reviews from the RPG blogosphere by checking out the hashtag #Endies2025 on socials.

The Dice Pool

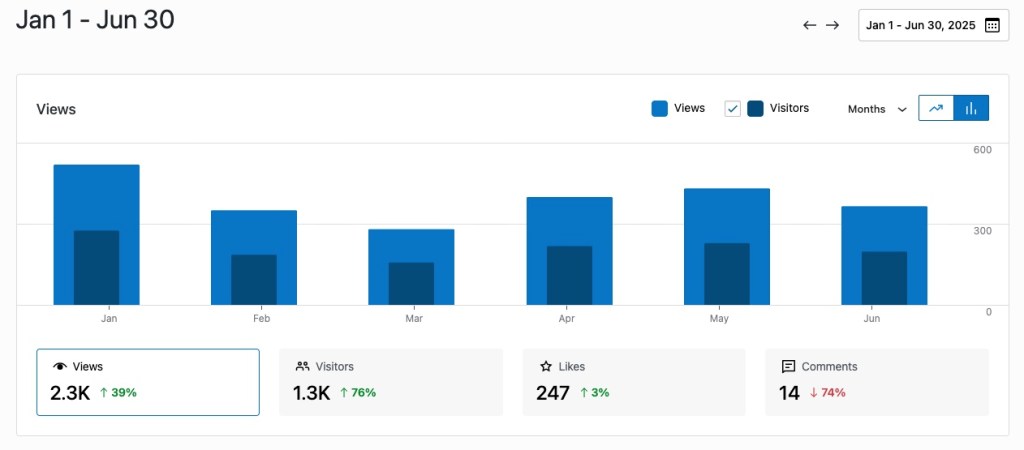

How has the blog gone in 2025? In short, it’s grown, at least in terms of views and visitors. In the first six month of this year, I got a little over 2,300 views. In the last six months, there have been over 5,200, bringing the total to over 7,500. That sort of increase is always nice to see, of course, even if it doesn’t seem huge compared to other sites. What I feel is feeding that growth is largely the sheer number of posts I’ve published. Including this post, I’ve published 96 this year, bringing the total on the site to 184. I get hits on a lot of them quite regularly.

Here are the top ten pages/posts:

- Homepage (Latest posts) – 674 – The rest of the numbers below are skewed because of this one. My homepage has that infinite scroll sort of thing going on, so it’s hard to see what visitors to this page are actually stopping to read. Although, I generally assume that it’s the latest post.

- Triangle Agency: Character Creation – 306 – I was fortunate that I published this one around the same time that Quinns released his review of Triangle Agency.

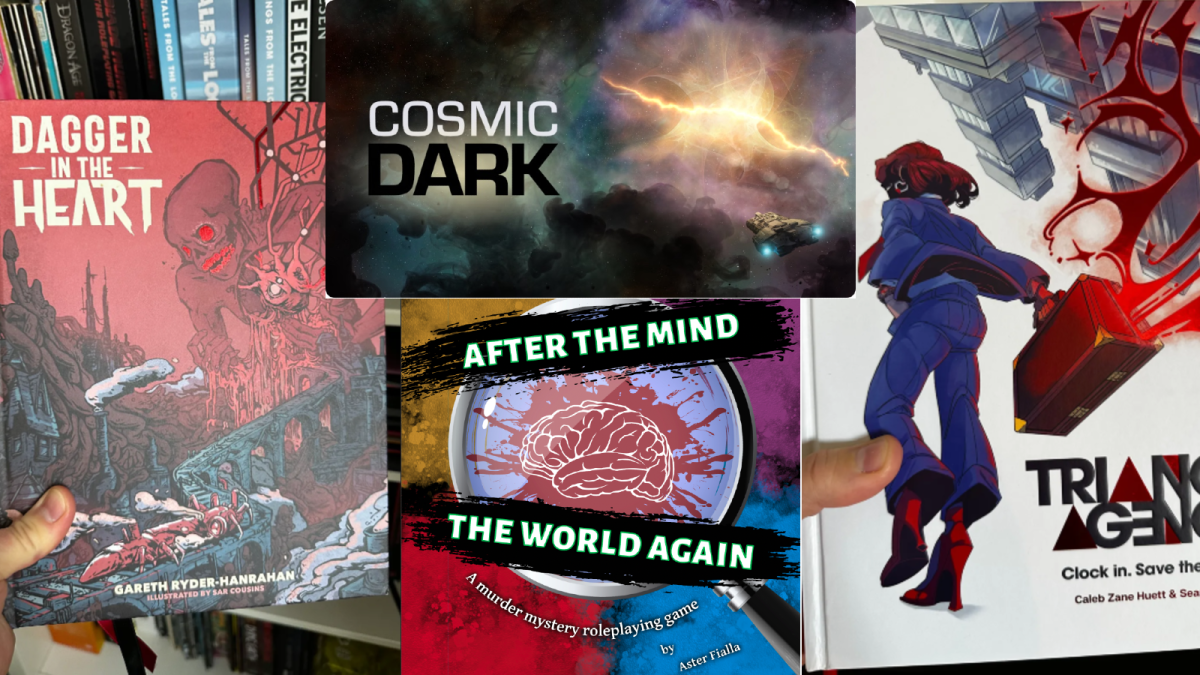

- Dagger in the Heart – 287 – I’d like to think that all of these views come from people interested in my review of the Heart campaign by Gareth Ryder-Hanrahan, but I suspect a lot of these clicks come from people looking for Daggerheart stuff

- After the Mind the World Again – 270 – This is the highest ranked post that was kindly linked by Thomas Manuel of the indie RPG Newsletter. He has driven a lot of traffic my way over the last year so I would like to thank him for that!

- Cosmic Dark: Assignment Report – 204 – This post was also linked by the Indie RPG Newsletter, as well as Graham Walsley himself on Bluesky. This is the sort of thing that makes me love the Indie TTRPG space so much!

- Alien RPG’s Hope’s Last Day: A Review 185 – Yet another post shared by Thomas Manuel. This one has gotten a few hits recently, I think due to the release of the Alien RPG Evolved Edition Starter Set, which has this adventure in the box.

- Inspiration – 175 – I re-shared the piece I wrote as a tribute to my brother last year. I think the traffic mainly came from family and friends, many of whom would previously never have known I even had a blog.

- Blades in the Dark Best Practices and Bad Habits – 164 – The generous and supportive John Harper himself, re-skeeted this one on Bluesky. Along with several other Blades-related posts. This has contributed to Bluesky becoming my second highest referrer.

- Ultraviolet Grasslands Character Creation – 146 – No idea why this one is in the top ten. I suspect its because players are desperate for UVG content and assistance in running it.

- Blades in the Dark GM Tools – 134 – Once again, John Harper shared this one on Bluesky.

What does it mean?

Not really sure, to be honest. I can see the line on the graph going up for views and visitors generally. Like I said, that’s nice. And I get a little thrill when someone shares a post, talks about it or recommends it. But I get very few subscribers; only 31 in the last year and a half. I understand that, to be fair. I don’t claim to be a news site. I’m not reporting on the latest releases or current events in the industry most of the time. I’m writing what I want, when I want, and I’m generally happy with that. I also have no frame of reference; I don’t know what sort of numbers other similar sites might expect to get, so all I can do is compare against my own past performance. What all this means for the site is that I’m going to keep going and hoping that you are getting something out of it, dear reader.

Tables and Tales

This has been a banner year for games in our little, local TTRPG community, Tables and Tales. 2025 was our first full year in operation, having started only the previous summer. But, if things continued this way, I’m sure we’d all be very happy indeed.

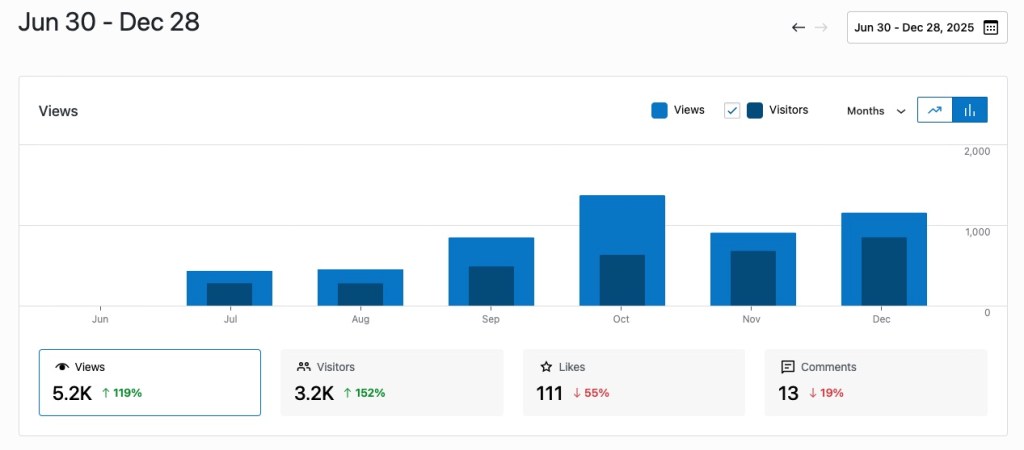

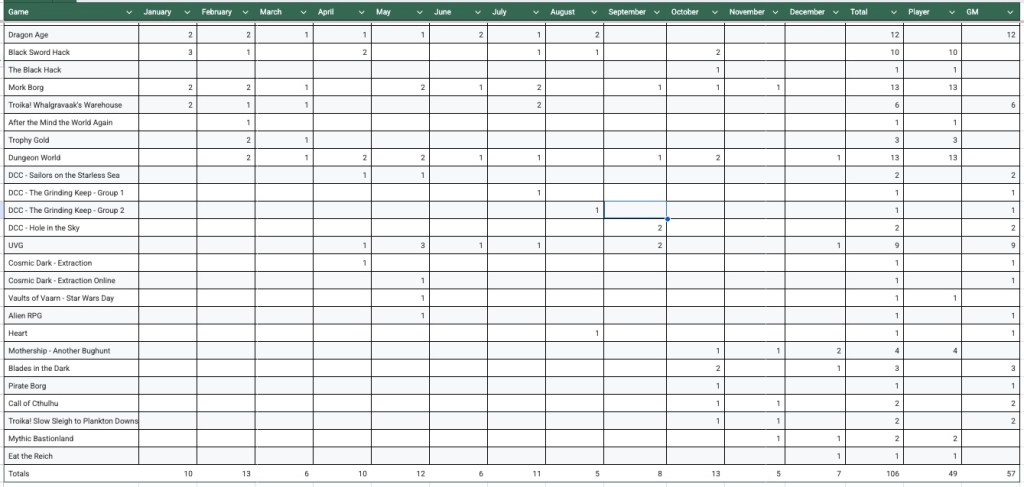

I put together a spreadsheet to measure the exact number of games and sessions I was involved in over the year. Here’s a link to it, in case you’re interested. Otherwise, here’s a screenshot.

As you can see I played in or ran a total of 106 sessions of 26 games this year. This is a lot. I don’t have any numbers for previous years, but I would go so far as to say this is far more than I have ever played any previous year of my life. And, not only that, but I’ve played with more different people than ever before, 17, in all! Our community continues to grow slowly but manageably. We’ve even welcomed a couple more members from a little further afield. We now have folks in the Ireland, North and South, Scotland and England! As such, we have begun to run a few more online sessions, though the vast majority are still in person.

If you’re interested in learning more about the games in the spreadsheet, I’ve written about most of them on this very blog! You can use my handy-dandy search bar or the tag cloud in the side bar (you might have to scroll to the bottom of a post to see these things if you’re on mobile.)

I don’t have the full numbers for all of the community’s games, but I can confidently say I have been involved in about 85% of all sessions played this year so you could work it out from that. Is this sustainable for me? Just about! You can see that there were months where I played far fewer sessions than others, August and November stick out there. This was usually due to illness, work, holidays and other scheduling issues. We also mix it up quite a bit, as you can tell. We run lots of one-shots and short campaigns and these serve to keep things interesting. We also tend to take breaks from longer campaigns to try to avoid burnout or boredom. Our October Halloween Event was brilliant for this. Tables and Tales played 5 or 6 games that month that we had little or no previous experience with. These strategies are generally quite successful in achieving those goals.

I would never be able to pick out a favourite from the list but I want to give a particular shout-out to two campaigns. The Mörk Borg campaign, the Great Borgin’ Campaign, as it was named by our GM, Isaac, had the joint highest number of sessions in 2025. Thirteen sessions! It was a stonking good run, which combined Isaac’s own home-brew adventures, dungeons published specifically for use with Mörk Borg, some system-agnostic stuff and even one adventure for Warhammer Fantasy Role Play! Every session was a delight and every PC was a filthy, murderous nutcase in the very best way (another shoutout to Jude, Tom and Shannen, you absolute weirdos.) And almost all of us (RIP Torvul) made it to the very end of the world itself. Or was it just the end of a virtual reality video game that was being enjoyed by potential future characters in Cy-borg, Mörk Borg’s cyber-punk sister? Hopefully!

The joint highest number of sessions was in the fantasic Dungeon World campaign run by Tom! This is fully homebrew, from the world and the species to the dungeons and the NPCs. It has been quite collaborative at the table and it has had an intimate feeling with just three players, me, Jude and Isaac. You can check out the post I wrote on the game earlier this year, here, where I talk about how good and unexpected it was to get such an old school feel from a PBTA game.

HNY

Dear reader, as you can see, I’ve had a good year on the blog and in Tables and Tales. Here’s hoping 2026 will be even better. Happy New Year to you and yours!