Where shall we start?

This is always the first question I ask myself when starting a new game. It doesn’t really matter if it’s a one-shot, a short series of sessions or an open-ended campaign; the beginning sets the tone for the whole thing. If you start your PCs off trapped in a haunted house with no prospect of escape and a murderous ghost hunting them, you have made a pretty firm statement about the kind of game you are all there to play (or your players will see it that way at least.) Equally, if you start with a scene from each character’s home life, interacting with their family members and discussing their everyday problems, you are establishing a sense that this is the type of game where that kind of thing will happen again (or you should be.)

You can use the start of your game to establish a theme too. Maybe its a horror game involving frog mutants who want to feed your players souls to their unholy tadpoles, you could start in their camp at night, describing a croaking, ribbiting chorus that grows in intensity and volume through the night, ensuring that none of the party get any rest. Embed in the cacophony the true name of a PC and you have the potential for fear and suspicion if not outright horror.

Control

Three sessions in, there’s one PC who has decided to attempt a bloodless coup on the streets of the town at the centre of your adventure, another who has set their heart on wooing one of your NPCs of lesser importance and a third who just wants to sit in the tavern and spread rumours about the sheriff being a cannibal. It can feel like you are out of the picture sometimes (and that’s not necessarily a bad thing, dear reader. The best sessions happen at the whims of the players.) At the start, though, you, as the GM, have control. It relates a little bit to the world building work you’ve been doing, or not doing. After all, you made up the place they start in, or at least, you read about it in a published sourcebook or module and interpreted it as you saw fit. You know the places involved, you know the relevant NPCs, you know the setup, even if you have no preconceived notions about how it’s all going to go down in the sessions to come. With that knowledge, you start with an advantage, for the time being, at least. Before long, you have to hand things over to your clever and inventive players and they’ll have burnt down half the Silver Quarter while introducing the roller skate to Spire.

But, more important than your behind the scenes knowledge, is the situation they start in. I’ve mentioned in medias res beginnings in the past. Frame the scene they find themselves in and make it tense or truly fantastical or horrific or action-packed or just evocative. Start in the middle! It is the one opportunity you have to do this. You set it all up and see how they react to it.

In the Death in Space one-shot I ran a few months ago, I started them off being ejected from cryo-sleep as they approached the main adventure location, a mysterious space-station. They each got to have a moment to describe their characters and I explained they were seeing the debris field surrounding the remains of a planet that was destroyed in the recently ended wars and that they had to guide the ship through it! But then I used a series of flash-back scenes to explain what they were even doing there. I don’t think that’s even the first time I have used the in-medias-res/flashback combo to get into the action as quickly as possible while also providing some much-needed context. It worked pretty well as I recall…

It’s a fun way to get them all rolling dice quickly and failing quickly too, which is usually pretty important in a one-shot horror game.

Intros

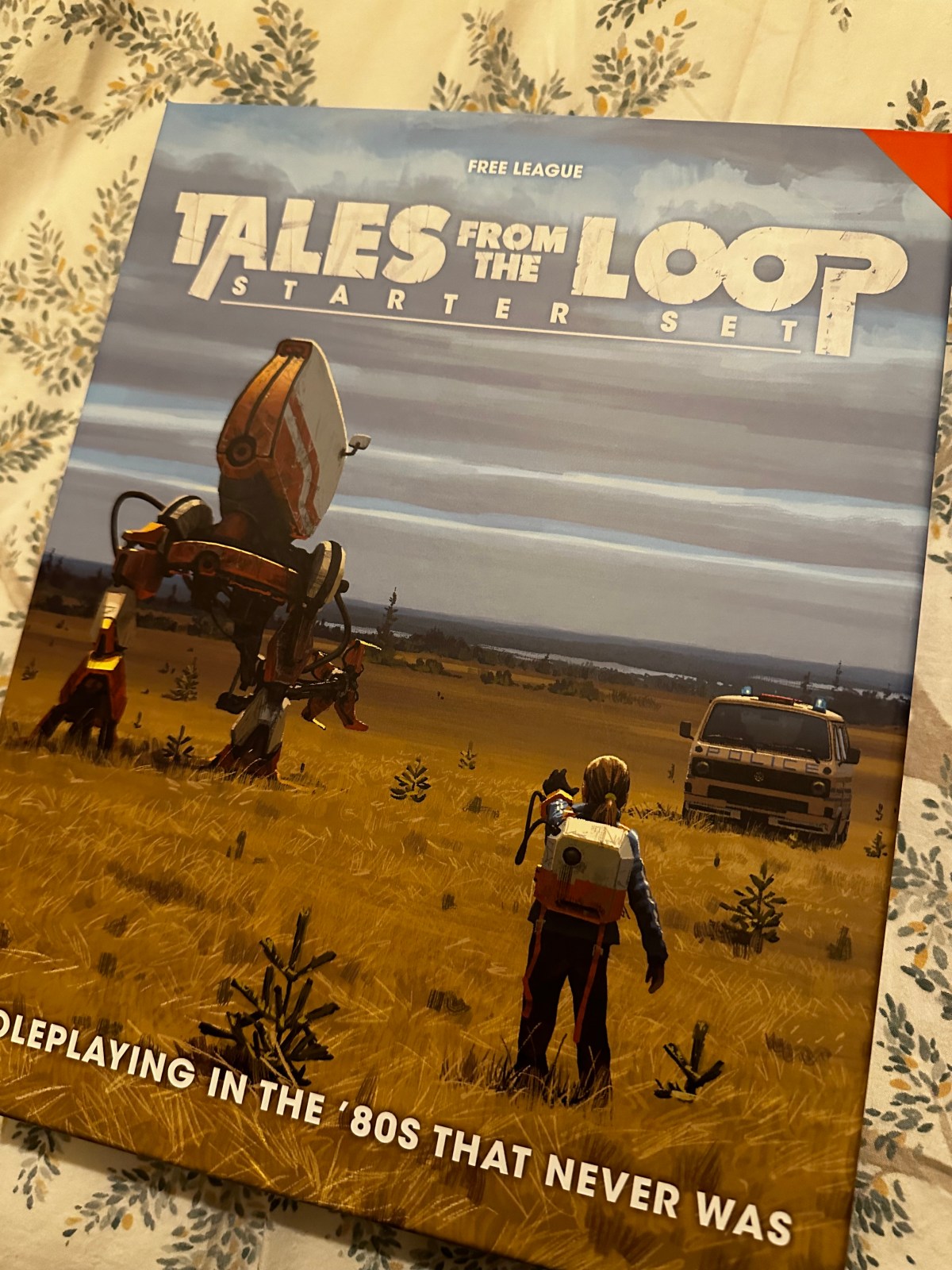

Tales from the Loop wants you to put the kids, the players’ characters, at the fore from the get-go. And deservedly so. These kids are created to have people who are important to them, problems that consume them in their regular lives, drives that motivate them and things they’re proud of. They’re rich and three dimensional characters before they ever get to the table. So, the game insists that you start a mystery (what TftL calls adventures) with a scene belonging to each and every kid in their home life or at school, with NPCs that are important to them, family, friends, mentors, that sort of thing. This is where the players get really invested in their characters. They have genuine and heartfelt interactions with the people of significance to them and they begin, immediately, to find their voice and their personality. It’s probably the best thing about a game that has a lot of good things going for it.

I stole the technique for the second campaign I ran in my Scatterhome world. It took place on the northern island of Erlendheim. The PCs all knew each other at the start since they began at 8th level and, in the fiction, had an adventuring party for many years, long ago. The adventuring life long behind them, I asked them to describe their mundane lives as a farmer, an advisor to the Jarl, a guard sergeant and a village priest and made sure to include people and places that were important to them. I focused on who and what they loved because I knew I was about to fuck with all that.

I had learned a lesson, you see, dear reader. Oh yes. For those of you keeping studious notes, you will recall I described the start to the first campaign in Scatterhome, when I drowned the island nation and erstwhile homeland of the PCs, Galliver, off-screen, before the start of the game. They didn’t care about it, and I can’t blame them. I had never given them a reason to.

In Erlendheim, they were more focused on saving the druid’s kids, ensuring the safety of their families and homes, protecting their futures.

Tug on those heart-strings, GMs.

Scenic

There is a subtle art to the transition from the start of an adventure to the meat of it. Or there is if you don’t subscribe to the philosophy that adventures should happen in scenes.

Usually, the end of a scene is obvious in a movie or tv show. It normally shifts perspective or location or time. So, if you want to do something similar in a game, someone needs to just say it’s over and move to a new scene. Sometimes that’s the palyer who wanted the scene but usually its the GM. I would rarely have done something so bold as to declare the end of a scene in a game of D&D as a more trad DM but it’s so freeing to do it! Just like you framed that first scene at the beginning of your game, you soon realise that you can frame and end any scene at any time (within reason.)

Looking back at the Tales from the Loop example from earlier, I noted that each kid gets a scene about their home life. Together with the player, you describe the kind of scene it is going to be, improvise it and end it when it feels right. When you move on to the investigation part, you can cut to a scene with all the kids in it, where they are staking out the suspicious machine that appeared in the nearby field overnight to see who is responsible for it and end that scene when they have gotten everything from it they can. Easy.

Using scene structure is even built into some games. Spire and Heart use scenes, situations and sessions like other games use rounds, days and long-rests. They are left deliberately vague but some powers and abilities work only within the current scene or situation. I have embraced the vagueness and it didn’t even take any adjustment. It was instinctive.

In the next post I am going to write a bit about endings, which, in my experience, are so much more difficult.

How do you like to start your games, dear reader? Let me know in the comments.

Discover more from The Dice Pool

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Did a few sessions or rp/dicing back at the old uni with some members of SCA. I usually

just tagged along with group, meandering in the back. Lots of fun. Overall, I found myself more

attracted to the game art than anything. Gamma World always had interesting art.

Yadda, yadda, yadda, I liked your post. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I assume you mean the Society for Creative Anachronism and not the Specialty Coffee Association!

You know, I always loved the Gamma World artwork too. It’s got this very specific style of retro-futurist-postapocalyptic-dungeons-and-dragons feel to it that tickles the right part of my brain.

Even just your mention of it here made me want to pluck the book off my shelf and have a flip through it. Love that picture of the mounted gamma-knight fighting a cyber-mutant with a laser bazooka…

LikeLiked by 1 person