The Match-maker

What a good brother and friend! Maryk just wants his friend and his sister to be happy together forever. A laudable and romantic ambition, I think we can all agree. He wants to use his skills and abilities to allow love to flourish and happiness to reign! Perhaps he can even do enough good to wipe out the curse his short life has laboured beneath since his very birth. I’m sure it will all work out perfectly.

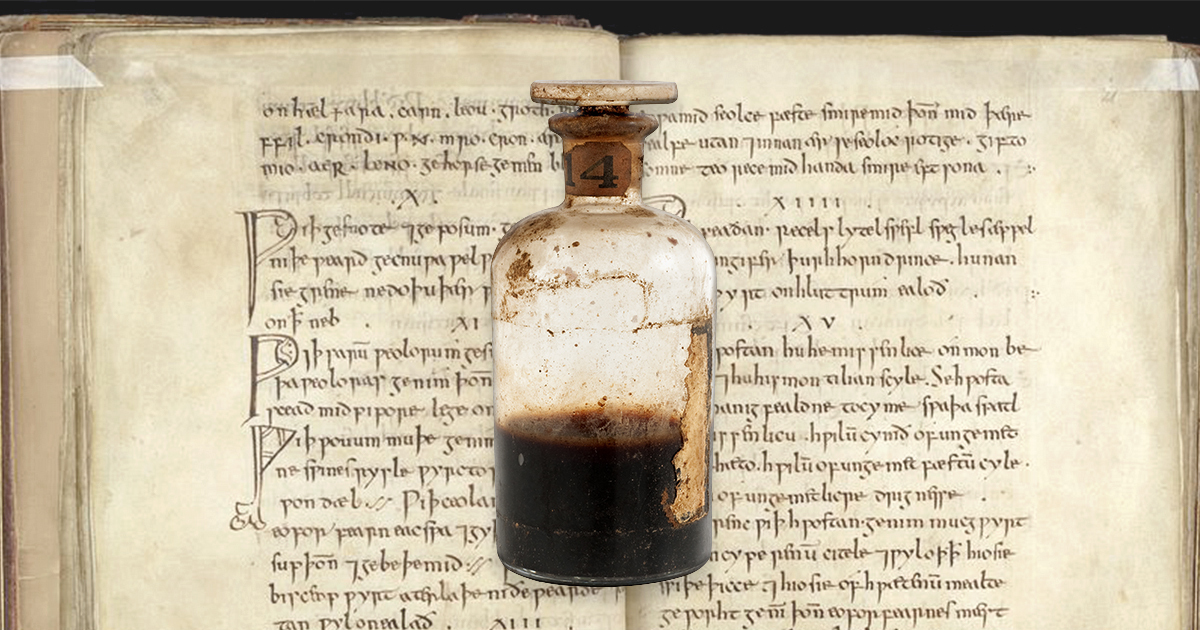

Chapter 9: The Consequences of Magic Potions

Our water had monster’s blood in it, although this was never verified by a visual inspection of the site, it is the general consensus, or, at least, the belief. No-one drank from it or fished from it; certainly no-one swam in it. A few brave boatmen fared the black waters but most people got no closer to it than the crumbling wooden bridge over it. It did not smell bad or feel strange to the touch and it even looked quite beautiful sometimes when the sunlight or moonlight struck it just so but everyone knew it could kill you.

I knew that but, also, I knew I could make it not kill you. I could do it, at least, I could now…not then, though.

Inevitably, Cobbles knew a man who ran a boat. He brought trade goods from Pitch Springs to Priest’s Point on the coast. In exchange for a day’s work, this man was willing to look the other way when Cobbles filled his canteen with poison water. This was the final ingredient. His love was only days away from embracing him now.

We met by the fountain in Saint Frackas’ Square and he handed me the canteen. “I’d like that back when you’re finished with its contents. I’ve had it since I was wee,” he said to me, as if he were not performing the single most important act in his life. “Of course, of course. It’s yours after all,” I replied as if I was not about to seal my fate. “So, how long?” he asked. “Perhaps two days; you shouldn’t rush these things, you know,” but I should have said three days or four, not two. “Fine, fine!” he said, “I can’t wait, eh? Primmy will be mine just like I’ve wanted all these months.” I nodded and shook his hand. “Oh!” he said as an afterthought and yanked a single hair from his curly head, “You need this too, right?” “It wouldn’t work at all without it, Cobb,” said I, taking the hair. We said our goodbyes and I went to stash the pitch water in my laboratory.

Later, I sat at the dinner table and discussed the events of the day with Mrs Blanintzi and Primmy, who beamed her happy smile at us both and spoke of her friend, Olka. Olka was in love with the baker’s lad but had a boil the size of a grape on the back of her neck. So, obviously, she couldn’t show an interest in the boy in case he should fumble across it when they were courting. “Courting!” said our governess, “There was no courting in my day. You young people have no morals. I should stay away from that Olka girl; she sounds like a tart. Courting! In my day you married the man your parents arranged for you and that was that. Courting didn’t come into it.”

I sat and smiled and enjoyed the company of my family. I wondered what it would be like in the house when Primula left to marry Hindryk (that’s Cobbles’ real name incase you’ve forgotten. I know I often did.) It would be odd but I thought I’d like to have the old place mostly to myself. Mrs Blanintzi, after all, wasn’t so bad. She had strict rules but was less strict in their enforcement.

That night I prepared the equipment to distill the poison out of the black water and began the process. It would take 36 hours by my calculation. I was off. I should have experimented on a small volume of the liquid first to be certain of my calculations. I should have given some to one of the many rats that were so easily caught in the cellars and gutters of the town to see it’s effect. I should, perhaps, have thought twice about the entire damned undertaking. Refusing to craft the potion for Cobbles at this point would have been cruel to him, certainly. I might have lost a friend over it. But looking back at it, I can see how much I might have, not just retained, but also gained. A whole life of learning and maybe even teaching, of respect from my peers and maybe even of those far above my own station. Master Gedholdt had met His Majesty, the King. He displayed a medal on his mantle. I could have been ten times the sorcerer that my master was. Instead, I made a love potion for my friend.

Two nights later, I took the ruby liquid which had resulted from the distillation of the Pitch Springs Water and mixed it with the other ingredients in a small cauldron I had for just such purposes. It should have been the colour of beets when it was finished, instead it was the colour of stout. I paid the colour no mind, trusting instead in my own expertise. I had never made a potion that did not work as it should. This was an indisputable fact of which I was very proud. So I bottled the stout-coloured elixir and went downstairs with it. My sister had just arrived home for dinner and was at the door shaking herself dry like a dog. The weather had been miserable all day. Sheets of rain and hail had been sweeping over the town since early morning. I had not been out in it as I had been busy with the potion and Master Gedholdt had not needed my services. I helped her off with her coat and hung it to dry by the fire. Surprised, she smiled at me and said, “What’s all this about, turnip-head?” she said with suspicion. “Why, Primmy! I don’t know what you mean!” I answered, all innocence. “You want something…” she was right of course. “Well, there was something small. I made something, a concoction I’m thinking of bottling and taking to the market next month…” I started. “And? What has that got to do with me?” “You’re too clever, sister of mine. I thought, since it might bring in some extra silver it would allow you to, perhaps, cut the number of hours you have to toil for that old bat if it works out. But I need someone to test it first. Just to taste a bottle of it to see if folks would want to drink it.” Smile slackening, Primula asked, “what does it do?” Little did she know…”Do? Why, nothing, not really. It’s more of a savoury fancy. A beverage for those who would rather not become inebriated.” “Oh. Why would someone want that?” She asked “My good sister. Our family has been lucky enough not to have endured a religious education or upbringing but many are those worshippers who are forbidden the taste of liquor. Followers of Saint Kannock, for example, though not completely abstinent, are not permitted alcohol at the weekends. That is when I intend to sell my beverage outside their temple.”

“Smart,” said she, and took the bottle. The lot was gone in a nonce. She smacked her lips said, “Not terrible, brother,” swayed in place, groaned, “something, something’s wrong,” stumbled two paces through a little side table and towards the fireplace. I caught her just in time, preventing her immolation by only a fraction of an inch. We fell in a heap on the parlour floor and I was laughing, what a jolly joke she was playing on me! When I took a breath I realised… Primmy was not laughing, she lay on top of me not even moving, not even breathing. She had fallen face down and I could see her pretty hair all in a mess, duller than normal. I struggled out from under her and saw her right arm trapped uncomfortably beneath her and her legs stuck out at odd angles. I had to be sure. Of course, I knew what this was, but I had to be sure. Turning her was not easy. As I said, I was wasting away and my muscles were weaker, then, than when I was a six year old boy. But turn her, I did. The deep blue veins in her face and neck stood out as if the blood had tried to force itself out through her skin. The eyes in her pretty face were like great black pearls, glistening with a liquid light but the worst was her mouth. Her teeth had all become like shards of coal and her tongue, also black, protruded rudely from between them. She was dead and I had done it. I did weep, if I remember clearly, I did, but I do not recall wailing or crying. Silently, I took up the empty bottle of Love Potion and pocketed it, then I went downstairs to the kitchen and informed Mrs Blanintzi that something had happened to Primula. I thought only of Cobbles then, oddly. What would he do now that his love was dead and gone? Would he be alright? I followed the old woman upstairs, thoughts occupied by the plight of Cobbles all the while. The governess stopped and stooped and wailed over my sister’s still-warm corpse and I thought that Hindryk’s life would be ruined now. Mts Blanintzi ran into the square and I followed as if attached to her by a string. I looked around and saw him there, Cobbles looked at me and I knew that it was even worse than I had thought. He knew. Cobbles knew I had killed her.

No-one else knew what killed poor Primula. The town doctor looked at her but the best he could come up with was, “she was poisoned.” He was not incorrect of course, but he could not be any more specific. A letter was sent for my father to return immediately but he was far away on the borders of our country defending a fortress against an infidel foe. He might not have been able to return for weeks and essentially, it would have been too late for him to do anything. Perhaps if he had been there I might not have continued down the pitch black path I had laid in tomb-stones before me. Perhaps, but then again, perhaps not. What is the point in considering such might-have-beens when the past is immutable and the future, for me, at least, forever ruined? At the time, I had only one thought for the future. I had the thought that if I was going to be a sorcerer then I should be able to gain from it, and so should Primula. You have guessed by now, of course, what was on my mind. I did not have the knowledge. I could not perform the spell, if it even existed, because I did not know it. I knew where it could be found, though, and I knew how to get it. I just hoped that Master Gedholdt had not heard of Primula’s death because, if he had, he would certainly prevent me from even entering his house. I had to go that very night. I was just lying awake in my bed, considering the problem, as I saw it, of my sister’s death and how to fix it. So, once I had hit upon the answer it made sense to go immediately.

I skulked for an hour beneath the tree in front of my Master’s house before the lamp light went out in the front window. He was finally off to bed. I saw the lamp snuffed out from my vantage point and wondered why Gedholdt did not simply use a light spell all the time. I waited another thirty minutes and then crept, black-clothed, to the window. It was an old one with a latch, which would come loose with a jiggle or by the simple manipulation of a magic hand. I cast the spell, whispering the words and performing the actions as untheatrically as possible (this is a difficult thing to achieve when performing magic. It is always a performance and so, usually requires grand movements and projected voice.) Once it was open, I climbed awkwardly through and into the front room. The book I was looking for was not where I expected it to be. I could not have foreseen this as I had never been in the Master’s house so late before. The Master’s current work was the study and translation of the “The Emperor’s Libram, Royal Magic” and whenever I had previously been to his house it was placed, open to a particular page or closed against prying eyes on a stand on his desk. He often spent eight or ten hours a day at the libram, whispering and memorising and making notes. I did not know that he moved it at night. I went to the strongbox in the kitchen. I was certain that’s where he would secure it. Gedholdt kept all his valuables in the strongbox, thinking, incorrectly, as it turned out, that if a thief came to rob a magician, he would not expect the valuables to be there. It was an unassuming but large box with a sturdy, but not magical, lock. I had taken great care in creeping through the house and slowly shifting open the door but I knew the box creaked unnaturally when it was opened or closed. I had no choice, of course, but I steeled myself for the possible repercussions of my next action. Everything up until this point, my master might have forgiven. Breaking into his house was one thing but the Emperor’s Libram was not only his most prized possession, it was also the most dangerous by an extremely wide margin. I did not hesitate long before casting the “Open” spell. The sturdy lock was helpless against the magical spell; I heard the click and then I pushed up the lid. Wood groaned, iron scraped and I gasped. I cast another spell, “Levitate” this time, and took the glittering gold book from its ineffectual hiding place beneath a pile of tea cloths. As I did so, I heard a disturbance upstairs. The groans which had woken my master were echoed by the groans he made in the floorboards. He yawned and said something to himself. I could hear him coming downstairs. I pushed the floating book before me and ran for the front door, heedless, now, of the noises I made. The footsteps on the stairs quickened but by the time I heard him reach the bottom I was gone.

Home again, I had to find the spell. I floated the book up to my lab where it occupied most of the free space. I sat cross-legged on the attic floor and studied. Knowing that Gedholdt would figure out soon enough who had performed the daring robbery, I worked as fast as I could. The wonders writhing restlessly on every page made it difficult to skip anything and I could finally see why my master seemed so obsessed with it. But there was just one spell that I needed. Just one. I was confident, once again, in my ability to accurately translate such ancient writings. The spell I was searching for would be called “Revive.” It took two hours but I discovered it near the back of the book in ink of red and black. The sun would soon be up, I had to move fast or no-one would ever believe that she had simply recovered from her injuries.

I had devised the story that I would tell to explain her revival, if, for some reason, I was questioned. She had not died, no, she had but fallen into a semblance of death, a coma-paralysis caused by whatever poison she had consumed. When I went to visit her body in the temple, that night, it had worn off. She awoke, groggy and ill, right enough, but alive!

I hurried to the Grand Temple of Mictus, Saint of Souls, where the dead were laid before burial, armed now with the knowledge that would make things alright. If only I had managed to do this before word had been sent to my father, I remember thinking, I might have saved him some heartache. He would be happy, still, to find her alive when he arrived and she and he would enjoy a pleasant family visit, instead. Ha!

The door to the temple was unlocked, as always, but there did not seem to be anyone around other than the dead. It was a long, high-ceilinged, marble and granite, grey and white space. The tiles beneath my feet caused my footsteps to echo maddeningly as I walked the aisle, guided by dim torchlight. My sister was not the only occupier of the altar that evening. Two more corpses flanked her, all three draped in red cotton sheets as tradition demanded. I looked at her and thought, how dead she looked. She did not look like my sister anymore, she looked like a thing, an object, no desires or worries or likes or dislikes or emotions or…well…life. A second-guess stayed my lips as I approached the corpse and set my body in the opening pose of the spell. Maybe she’s the lucky one, I thought, maybe she is the one to have escaped this world of pain and disappointment and suffering and toil. Then I thought again of Cobbles and his misery and his knowledge of my murder and I proceeded. It was a long spell, and I performed it for close to an hour. As I reached its final syllable and flicked my wrist with the last movement I heard a cock crow and then I heard the temple door creak open.

“What are you doing? What are you doing here? What are you doing to her, you little wraith? Haven’t you done enough, already? Haven’t we done enough!?” It was Cobbles, come to pay his respects and beg her forgiveness as well, of course. I lowered my arms and turned to face my friend as he ran towards me up the aisle. I shifted a step backwards and almost tripped over a rug. “Its alright!” I cried, “She, she’s not dead after all, she’s not, look!” I could hear her move behind me on the cold stone altar and I knew then that it had worked and that I had performed a miracle, that I was blessed, even. I watched my friend slow a little and, just before he had reached me, stop, looking, gaping at the miracle behind me. “What did you do, you little monster?” he breathed. Finally, I looked and realised that it had been no miracle, it was yet another curse I had lumbered myself with. Primula, still wearing her red cotton sheet had slipped off the slab she had occupied and begun to shamble towards Cobbles, arms bent at the elbow, hands pointing in his general direction, eyes, still black as coal, rolled back in her head and mouth hanging open limply. There was that slug-like tongue sticking straight out and around it came the sound, a groan and a scream in one, high pitched and low at the same time, echoing out through a jagged cave of a blackened mouth. Her pallor had not changed from the time I entered the temple, she was grey and blue and black in splotches and her veins still protruded startlingly from the skin of her face and neck and now her hands and her feet too. Nor was she alone. Her two altar mates had risen now also, one a burly corpse of a man who seemed to have encountered some sort of agricultural accident as he was missing his left arm from the shoulder down. His colouring was more red and pink with blue spots but he, too, was black around the stump of his lost arm. The other one was a child no more than six years of age. A girl I think, though it was difficult to tell. The corpse presented nothing more than a burnt and ruined face, lipless, lidless and hairless, its unsheathed teeth chattered horribly as it worked its charred jaw.

I stumbled away from them, Cobbles and his opinions and his troubles vanished from my mind but my feet had lost all sense and I fell backwards onto the tiled floor, I hit it hard, jarring my shoulder and knocking my head to momentarily stun myself. Despite this, I saw what happened when they got to Cobbles. He had, perhaps, been paralysed by fear and disgust at my actions. Finally, my friend felt the embrace of my sister, not-so-pretty Primmy now. She kissed him and he screamed as she came away from his face with a sliver of it in her teeth. The others surrounded him then and I looked away as he screamed horribly for another ten seconds or ten minutes, I don’t know. When it was over, I was left, still on the floor with the blood of my friend, Hindryk, pooling about me. My walking corpses had gone, they had left me alone and gone out into the town. I took off my gore-soaked jacket and threw it over Cobbles’ grisly remains, then I ran out into the Pitch Springs dawn to follow the trail of blood. Unfortunately, they had split up. What could I do anyway? I was just a boy still and all of my skills were failing me. I had killed my sister with a magic potion and then revived her to a vile state of undeath along with two others. They were all, no doubt, decent people who did not deserve this treatment. Everything I did to try to fix things only exacerbated my problems or created brand new ones. It was time I stopped. It was time I left.

Decision made, I ran to our narrow house on Saint Frackas’ Square, retrieved the Libram and ran to the bridge over the accursed pitch water and left Pitch Springs behind for good, or so I thought.