Waku Waku

Dear reader, my excitement is threatening to overwhelm me. As some of you may know, I studied Japanese in university and lived and worked in Japan for about three years in total. It’s hard to put into words exactly how I feel knowing that, this weekend (probably yesterday by the time I publish this post), I’ll be going to see the Ireland vs Japan rugby match in Dublin and next weekend I’ll be finally going back to Japan for the first time in eight years! I think the right word is probably わくわく (waku waku, loosely translated as excited.)

Anyway, as a build up to that, I thought I would look at an RPG based on a Japanese historical period.

Kanabo: Fantasy Role-Playing Adventure in Tokugawa-Era Japan

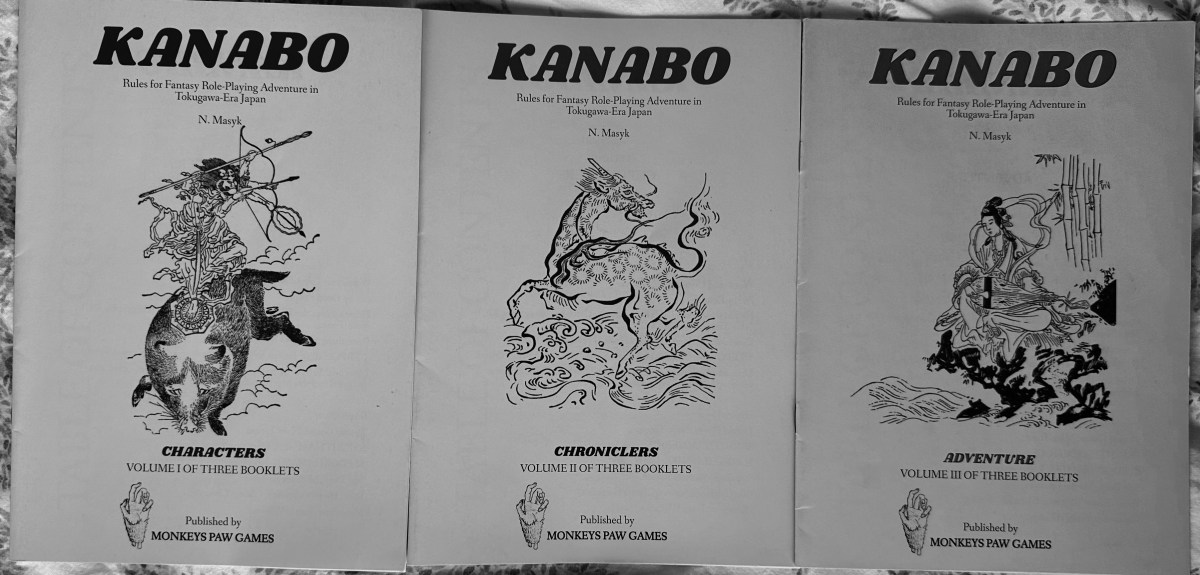

A Kanabo is a Japanese weapon, a long metal club, adorned with spikes or studs. The game, Kanabo by N Masyk, is an RPG published by Monkey’s Paw Games. It comes in the form of three neat booklets, Volume 1, Characters, Volume 2, Chroniclers and Volume 3, Adventure. It was gifted to me by friends and all round good eggs, Tom and Isaac several years ago. I can’t remember which year exactly and I don’t see a publication date on any of the booklets so I am going to guess and say it was sometime between 2020 and 2022.

These booklets truly are only wee. The longest of them is 21 pages of A5. But they pack a lot into each one.

Volume 1, Characters

This booklet, as is the case for each one, begins with the credits. N Masyk did the words and the layout, “Dead People” did the artwork and the Hexmap uses the Highland Paranormal Society Cartography Kit, by Nate Treme. Finally, consulting was done by James Mendez Hodes. I think you will notice a peculiarly Western bent to the people associated with this project, other than the Dead People who are all Japanese (by the looks of their artistic styles) but remain conspicuously unnamed.

It starts off with an intro section that explains briefly what the game is about and suggests the use of safety tools such as Lines and Veils and the X Card. The “What is this?” section tells us that this is a game set in the Tokugawa period of Japanese history. It informs us that this is the time after the Warring States Period when the country is united but many wandering Travelers are abroad, “seeking fame, fortune, justice, revenge, or simply the freedom to roam.” That’s the PCs! I like this as a time period and setting. The Tokugawa era was long, more than 250 years. It was a time when Japan was cut off from the rest of the world, guarded its coast jealously and avoided the great changes that engulfed the other regions during the same time. The role of the Samurai was slowly being eroded, nobles were forced to pilgrimage from their lands to the capital under their own expense to keep them in line, the Shogun ruled the land and Japanese culture deepened. But I also like that there is a paragraph here on historical accuracy. Masyk takes pains to explain that, despite the potential realities of the place and time, as players of a game, we must strive to be inclusive before being accurate. Japan of this time was a place of terrible inequality, Kanabo at the table does not have to be.

The introduction section is reprinted in Volume 2, Chroniclers and Volume 3, Adventure. I wonder, in a set of booklets of such limited page-count, if this was necessary. Perhaps it was felt that the Characters booklet, meant largely for the players, and the Chroniclers booklet, meant only for the Chronicler had to both have it to refer back to regularly, but I would question that, especially as the Adventure booklet is also meant for the Chronicler exclusively. Maybe its so the kid who finds one of these booklets all on its own, tucked into a box in the dark reaches of a secondhand bookshop thirty years from now, knows what it is they’ve found.

Stats

The Stats section actually introduces the entire character creation process. Stats themselves are only one part of that. You roll 2d10+20 for each stat, for a maximum of 40.

I was expecting this ruleset to be a D&D clone or maybe an Odd-like but I was surprised to discover this is a percentile system. When you want to do something you roll a d100 and hope for a result equal to or under the stat you are rolling on. You will notice that this makes it necessary to roll really rather low to succeed, but there are several ways to gain a +10 to your rolls, such as using the right piece of equipment, possessing just the right skill, spending a filled segment of your Fate Clock or, in battle, gaining Advantage. There are three specific ways to accumulate +10s in a battle. If you want to disengage from combat safely, you can expend all of them and do so.

The Stats themselves are incredibly and deliberately abstract:

- Fire: confrontation, aggression, force

- Water: tranquility, inquisitiveness, exploration

- Earth: stoicism, calculation, discipline

- Wind: intuition, reflection, grace

As such, there is a lot of potential leeway in the decision on which stat to roll in any given situation. I like this sort of thing. I imagine Blades in the Dark style negotiations occurring as to how they might work out in play. However, I struggle a little with the whimsicality of the naming convention. It has a sort of mah-jong flavour to it, I’ll admit, which is not, in itself a bad thing. But, if you were to choose particular Chinese characters from the available mah-jong tiles, there are others that really describe human traits that might work better. I am thinking of things like 力, chikara (strength,) 心, kokoro (heart) etc. The use of the four elements makes it feel a little more like Avatar than any of the sword-fighting movies that inspired this game. It is a stylistic choice, though, and I’m sure it would work just fine at the table.

There are other elements to character creation, of course. Some of them remind me, quite delightfully of making a DCC character. Others have an Into the Odd feeling which I enjoy.

You can roll for your Chinese Zodiac sign. Whatever sign you roll, you can take it and apply a +5 to a stat that you think it reflects positively on. It would have been fun to have to apply a -5 to a different stat in this step I think.

When you roll on the Birthplace table, you will get somewhere like “Fishing Village,” “Hill Fort,” or even “Haunted Ruin.” Depending on what you get here, you will start with a different piece of equipment, such as a “fishing rod,” “spear,” or “lucky charm.”

Next up you roll on the Career table, which will give you another piece of equipment. Soldiers start with a matchlock pistol but Farmers only get a straw hat!

Your birthplace and career also allow you to list two things you know about or are skilled in. These can give you +10 to rolls in certain situations.

By rolling on the Curio table you might find yourself starting with a lucky cricket, a mask or maybe some rice balls. Each curio comes with a question that might help to round out your character.

After this you have a bunch of tables that will help you describe your PC. You have Mannerisms, Clothes, Face, Names etc. There should be plenty here to give you a very clear picture of your Traveler.

How to Play

This section lays out the rules quite economically. I’ve given you the basics already and there isn’t too much more to them than that, which is great.

There is a PBTA element to the rolls. You only roll when there is some risk, of course, but if you succeed, you do so without consequence. If you fail, you can still succeed, but with consequences. In combat, this means that you trade harm.

You get a Fate Clock on your character sheet. It has eight segments, which you will be filling and erasing as you gain and spend them. You gain a segment whenever you roll doubles on a d100 roll. I choose to interpret this as 11, 22, 33 etc. You can choose to erase a segment to give yourself +10 to a roll, prevent 1 Harm, recover 1d10 wounds or survive past your 5th wound. It’s a bit like stress in Blades in the Dark, a superpower that these Travelers have that allows them to contend against terrible odds and powerful forces.

Some few paragraphs are devoted to the idea of Travel. Kanabo assumes you will be hex-crawling and lays out the rules for that in relation to time, encounters, foraging, rest & healing etc. This is presented in a way that is player friendly and does not blind anyone with science. I appreciate it.

Character Advancement gets one very short section. Characters can choose one of two options at the end of each session, “increase a stat by 1” or “write down a new skill or piece of knowledge.” It’s neat and lacks frills. No room for confusion at all.

The booklet is rounded off with sections on hiring help, common equipment and refreshments. They are presented in several short and entirely non-exhaustive lists that are merely starting points for the interested player to do some research on what stuff might have been available in Tokugawa-era Japan.

The best part of the whole How to Play section is the list of Best Practices. Many of these will be familiar to the those of you who have been reading my series on Blades in the Dark recently. We have gems like, “Ask questions. Take Notes. Draw diagrams. Write in pen” and “Fight unfairly. Lay ambushes. Hit below the belt. Run away.” And familiar old favourites like “Play to find out what happens, and how it happens” and “Strive for victory, but revel in your defeats.”

Volume 2, Chroniclers

After the repeated intro section we get straight into a section on how to run the game. Let me reproduce here the entirety of that section:

You control the world around the Travelers and the people within in, and the places they have built for themselves. Fill that world with adventure, danger and magic.

There are no further words by witch I might describe or prepare you for the journey ahead.

The contents of this tome, much like the contents of the Universe, are mostly lies.

I think this is probably one of the most uniquely unhelpful such sections I have ever read. I understand that the author is trying for poetry instead of boring old instruction, but it reads as though they want you to think there is no advice that might help a prospective Chronicler. There is something to be said for the idea that a GM/referee/judge/whatever should trust their instincts, but it is certainly not always true. Also, there is an enormous wealth of real advice out there, both in printed books and for free on the internet. I understand the author had limited room here, so, perhaps they could have directed the newbie GM to the blogosphere, or a particular publication that they thought aligned with their own design ethos.

Anyway, as soon as they have described everything in the “tome” as lies, they go on to provide guidance on how to run the game… and it’s useful! It’s practical and answers the sorts of questions that would definitely come up at the table when playing Kanabo! Things like discussing the possible consequences of rolls before making them, determining the effectiveness of successes etc. So, my main takeaway from all this is don’t believe the bit that tells you its lying to you…

There are a couple of pages here devoted to describing very Japanese-themed encounters, we have Kappa, Oni, Kitsune etc, without ever using those words. I like the pared down descriptions and the minimal stats presented, and I can see the idea of removing the Japanese names so as to allow a Chronicler to set their game of Kanabo in a non-Japanese context. Or maybe it’s done to for localisation purposes. I don’t know really, but, personally, I would prefer to use the Japanese names. It feels wrong to me to do otherwise.

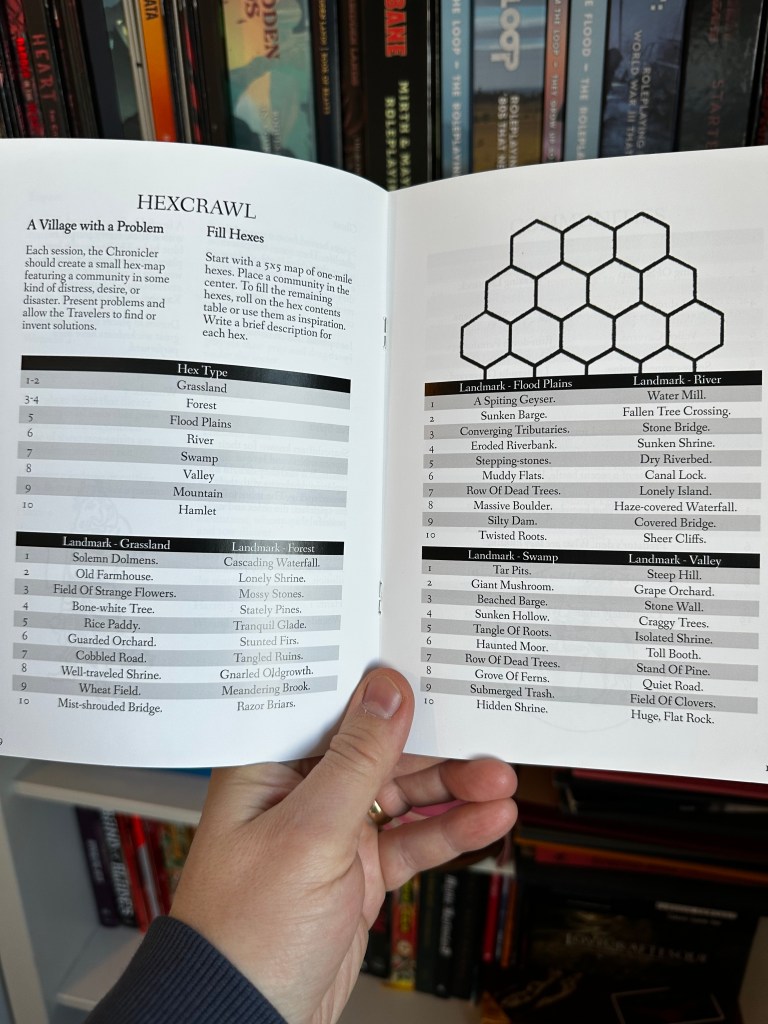

I think another very interesting element to this game is that, despite its semi-PBTA roots, you are expected to run it Old School. We have Weather tables, advice on rolling for encounters, an encounter reaction table and a whole bunch of tables to help you build your once-a-session hex map. These are, honestly, great. They are extremely practical and useful with lots of tables of landmarks for a variety of terrain types from Grassland to Hamlet. There are more tables for Factions, Communities, and Adventure Sites that would allow a Chronicler to build an engaging monster-of-the-week-style adventure with little to no prep required.

But, the advice for doing all this is limited within the booklet itself. The third of the the three booklets, however, serves to illustrate how it should work!

Volume 3, Adventure

This one if incredibly short, only eight pages, two of which have the intro again. After that, we get a bunch of ten point lists, which come together to create Peach Trees Village. The list of Locals describes each one in a single line, provides a piece of their dialogue and outlines an adventure hook. Here’s the first one:

Asuka. A farmer. So forgetful; “did my apprentice bring the cattle in?” Needs someone to go check. Something’s been at the cattle.

I love this way of presenting information. It’s incredibly efficient and is just enough to spark the imagination. You get something similar from the Shops and the Rumours lists.

Next, we have The Surrounding Wilderness section. This kicks off with a hex rose, already filled in to give the Chronicler an idea of how it’s done. Each of the 19 hexes is described in a similar way to the Locals above. Here’s no. 10:

Frozen wood. Snow-blanketed trees. A dead mile where nothing grows. Strange lights at night. What is causing the lights?

Once again, it’s just enough to spark the imaginations of both Chronicler and Travelers to perhaps pursue the mystery of the lights in the woods, without bogging you down with established fiction.

A “Searching, you find…” D100 table rounds this adventure booklet out.

Conclusion

All in all, I think this little RPG punches above its weight. I question some of the choices made regarding naming conventions, use of space and GM advice but otherwise, I am quietly impressed. I would like to try running it, but it will have to wait till after my own adventure in Japan!