Talk Like a Pirate Delay

I was really excited about this year’s Second Annual Tables and Tales Talk Like a Pirate Day Pirate Borg One Shot on September 19th but I was, unfortunately, overcome by some malady that day. We postponed it only to have a massive storm roll in off the Atlantic, forcing us to delay the departure of this vessel yet again. Finally, last Sunday the players’ pirates were ready to board the Repentant come hell or high water…

OK, I say they boarded it but it would be more correct to say they were taken aboard. I started them off in the expanded brig, area 1 on the map of the ship. They awoke, captured, stinking and hurting and minus all their stuff. Nevertheless, with a few improvised weapons they found lying around the cabin and the assistance of a skeleton thrall raised by the skeletal sorcerer, they managed to overpower their demon guard. This was the first of many obstacles to their defeat of the Ashen Priest commanding the ship and taking the Repentant for themselves.

The Scenario

The Repentant is an 11 page one-shot scenario for Pirate Borg by Zac Goins. It is published in the forthcoming sourcebook for that game, Cabin Fever, via KNOWN CONSPIRATORS, Limithron’s subtable for third-party creators. Cabin Fever is a treasure chest of extras for Pirate Borg including new PC classes, GM tools, a Bestiary, no fewer than six adventures as well as solo rules. I am one of the backers of the Kickstarter project so I got access to the PDF through that. I’m hoping to receive the physical rewards for that soon.

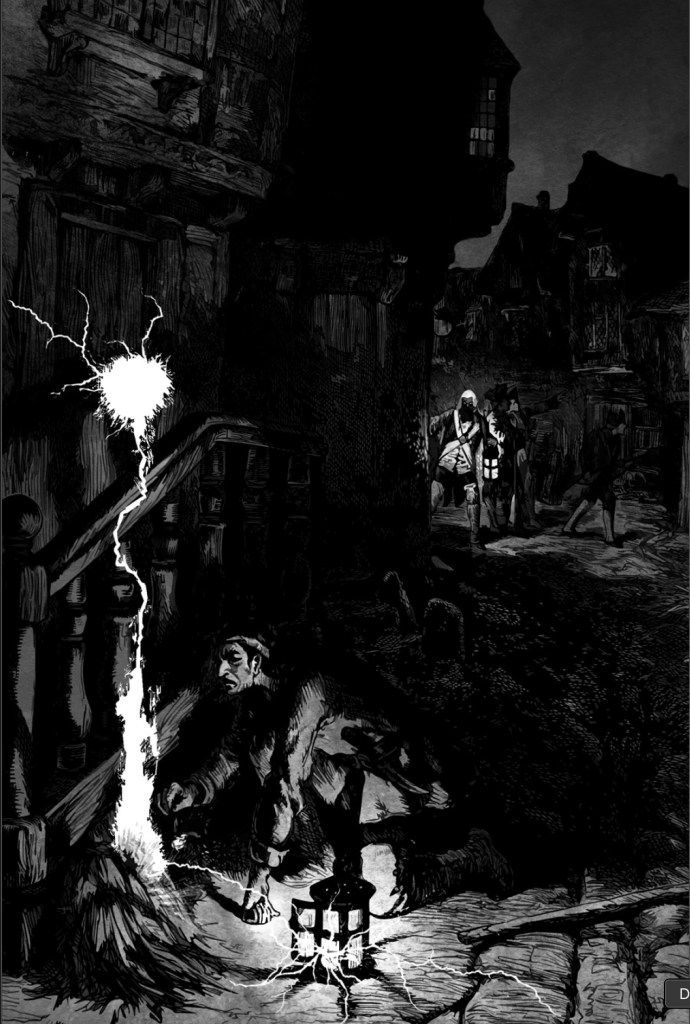

This scenario is presented in a typical Borg-ish style, with maps, and illustrations taking the lead in establishing the atmosphere. It’s almost all in grey and black, emphasising the theme of ASH. The layout is also typical with lots of tables, stat-blocks, keyed area descriptions etc being worked into the spaces between and around the artwork. I occasionally had to take a few extra seconds to find what I was looking for due to this but it was never a major disruption. In general it looks great and ewers relatively easy to use.

The Premise

The Repentant is a charnel ship, an unkempt brigantine with tattered sails and a crew of demons and cultists, commanded by a cadre of Ashen Clergy. Their goal is spelled out clearly in the three step plan on the second page. In summary, the plan is to summon demons, form an unholy pact with the Dark One, raid some settlements to take captives, kill ‘em, raise them as undead and then grind them up to make Brimstone ASH. This is a type of cursed and arcane narcotic on which the crew plan to make lots and lots of pieces of eight.

To be clear, the ship is the whole adventure. You could easily work it into an ongoing campaign, I think. It could be a random encounter or the goal of a mission. But, for me, it worked perfectly as a one-shot. It gives you everything you need in those eleven pages.

The Reality

There is a fun variety of enemies for such a short scenario. You have seven different types of possible demon (one for each deadly sin, with commensurate sinful powers,) the emaciated crew, the Ashen Vicars and the Ashen Priest who has a variety of fun powers. And if you deal with all those, there is a hold full of Brimstone Zombies, who have the power to promise your soul to the Dark One with a bite.

Although not every encounter ended in combat, almost all did. It felt inevitable in general. I started the players off where I did, in the brig because of the restrictions of a one-shot session. I wanted them in the thick of it from the start and escape gave them a powerful motivation to attack the terrifying demon, even without real weapons. Also, I figured the brig is area 1 on the map for a reason. The scenario does not explicitly indicate where or how you should start it as a one-shot, but if you take the hint, here, you’re probably not going to go wrong. It definitely got them into the action immediately. Without the timely and repeated use of Devil’s Luck and mystical powers in the first two encounters, at least one of the party would have gone down. The only thing is that it led to two mostly combat encounters in quick succession. Starting with them boarding over the rails or some other way might have engendered a totally different kind of adventure.

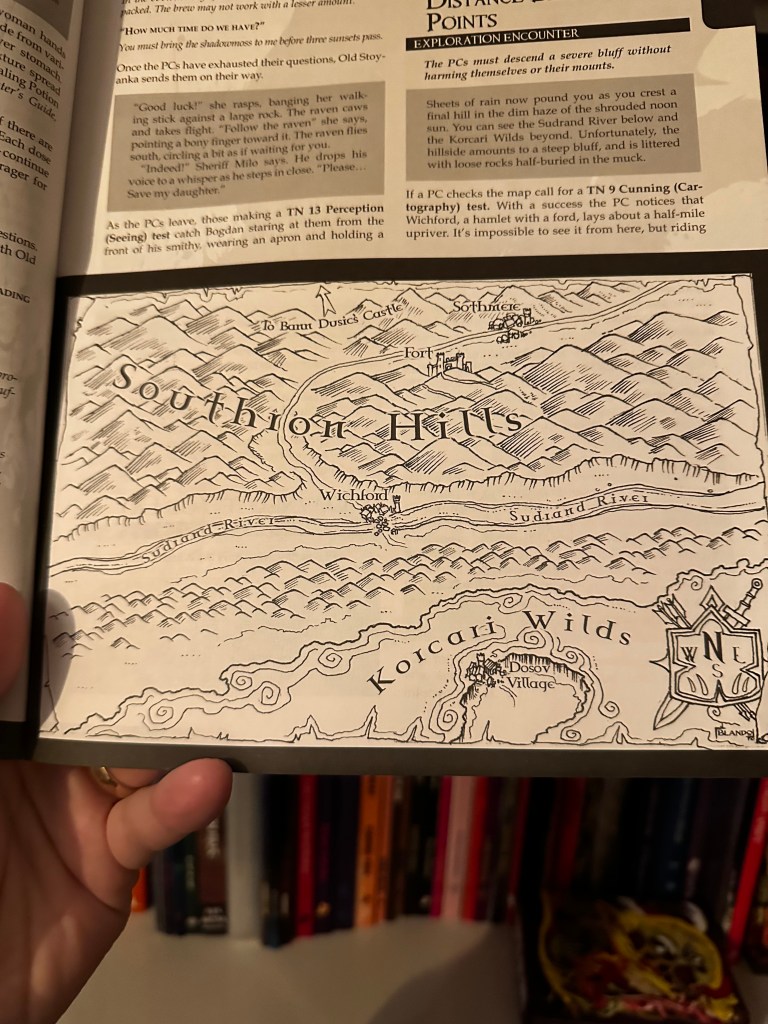

The map was fine. I was a little put off that three of the four decks had one side of the map cut off but it was of no practical disadvantage in play.

Tables, tables, tables. The tables are great, from the effects of the Brimstone ASH (different to the regular ASH introduced in Pirate Borg) to the “What did I just step in?” Table which I underused criminally.

My players only used the Brimstone ASH on their enemies, which was a shame. I think it’s because when they rolled on the table for those uses, they got 1s and 2s, which are very very bad. After I told them what else was on the table, they regretted not trying it!

6 The Devil’s inside ye. Immune to fire. All weapons’ dice size increases.

The Finale

I saved the Ashen Priest, the scenario’s main villain, for the end. He might have been found in either the captain’s quarters or the hold, according to the keyed locations, but, honestly, you could locate him anywhere to suit your own game. The PCs had done away with almost everyone else aboard when they descended into the cargo hold found him there, feeding zombies into the ASH Grinder. There were a lot of undead down there with him but the PCs made such short work of him that it hardly mattered. Then they got to take the ship as plunder, not to mention the undead and the grinder so they could enact the plan themselves!

Conclusion

This was one of the most well-crafted one-shot scenarios I’ve run. We played it in about three and a half hours, though, if things had gone badly, it might have been over after less than an hour! I did give them a couple of NPCs for back-up and in case anyone lost their first PC (there were two deaths.) This might have given them a slight advantage, if I’m honest, but everyone had a good time. Looking forward to trying out some more scenarios from Cabin Fever and the rest of the slew of new books from Limithron!