Old school play, new school rules

I have a post in which I write a little about a couple of the podcasts that most inspire me to play and write about RPGs. One of them is Fear of a Black Dragon from the Gauntlet. In it, Tom and Jason review a different OSR module each episode (more-or-less.) What I discovered early on, while listening to it was that they often did not use OSR rulesets to play the modules. Instead, they usually used Dungeon World, World of Dungeons or Trophy Gold. These are much more modern RPGs and, I think, they tend to use Powered by the Apocalypse and Forged in the Dark style rules. I have only just picked up Trophy Gold in the Codex-Gold magazine published by the Gauntlet back in 2019. So, I thought I would have a go at creating a character in this much more rules-lite game (compared to OSE anyway. To see how character creation went in that, go take a look at yesterday’s post.)

About the game

Essentially, Trophy Gold is doing the same stuff as Old School Essentials or D&D for that matter. It allows you to play an adventurer or treasure seeker who is drawn to dangerous, forbidden or haunted locales. The locales will push back. Unlike its predecessors, Trophy and Trophy Dark, which were made to play one-shots and tended towards the horror genre, Gold is more geared towards campaign play. It just doesn’t worry so much about your encumbrance or confuse you with bonuses that are actually negatives. It uses elements of Forged in the Dark games in its ruleset. It is described thus in the opening paragraph:

“Trophy Gold is a collaborative storytelling game about a group of treasure-hunters on an expedition to a haunted environment that doesn’t want them there.”

Character creation

So your character is called a Treasure Hunter in this game. This is because treasure is the aim of it. Your character is there to emerge from the dungeon or forest or ruins with heaps of Gold. But is it worth it? Will they even survive it?

Step 1 – Choose your Name, Occupation and Background

So, in direct opposition to OSE, we are starting with our name. I like this since, we all get named long before we know anything about ourselves, don’t we? The rules include tables for names, occupations (what you do in the party) and backgrounds (what you did before your treasure hunting days) So I am going to use them.

- Name: Valen

- Occupation: Smuggler. Skilled in dexterity, spontaneity, stealth

- Background: Retired Soldier. Skilled in tactics.

The rules encourage you to think about your background profession, why you left it and why you can’t go back. As a retired soldier, I think Valen has tired of killing at the behest of others. He left to put his skills to work for his own enrichment instead. He could never go back to taking orders now that he has tasted independence.

Step 2 – Choose your Drive

This aspect has an element of Blades in the Dark peeking through. Each character will have their own motivation for treasure seeking and I am going to roll on a table for it. But first it explains that you can stash the gold you earn from it in your Hoard. Once you get to 100GP, you can retire your treasure hunter. Blades in the Dark has a similar conceit where you get to hide away your coin in a stash until you have enough to comfortably get out of the game for good.

So, here’s my roll:

- Drive: Free the serfs of Bandung Prefecture

So, I don’t know where Bandung Prefecture is but it has fired my imagination. Perhaps my ex-soldier, while on a recent excursion to Bandung, discovered a village where the people were down-trodden and despairing due to the conditions caused by their lord’s treatment of them. There Valen met a man, a former soldier, who reminded him of himself to such an extent that he felt as though saving him and bringing down the cruel and selfish lord was essential. He just needs some funds to raise a rebellion.

Step 3 – Backpack Equipment and, if desired, Combat Equipment

There is an interesting approach to equipment here. You have three different categories, Backpack, Combat and Found equipment. You can roll on a table to see what your backpack starts with or you can choose from the table if you want stuff that suits your character. Importantly, your backpack starts with three items and three free slots. If and when you need something in a given situation, you check the table of Additional Backpack Equipment presented in the rules, and, if what you need is there, simply say it is occupying one of these slots. Then you write it down and mark off another slot. This reminds me of the loadout rules in blades in the Dark. These state that, when you are going on a score, you decide if you take a light, medium or heavy loadout. This determines how many items you can carry and also how much you stand out. But, importantly, you don’t have to say exactly what your items are until you need them in the fiction.

Anyway, I’m going to roll on the table for my

- Backpack Equipment: Fishing net woven of silver (!), Bottles, lead (6), Magnet

When it comes to choosing Combat Equipment, there is another rule that comes into play. That is Burdens. You start the game with a Burdens score of 1. That’s the amount of Gold you need to keep yourself on a day-to-day basis in between incursions (that’s what Trophy calls adventures.) However, it increases for every piece of Combat Equipment you choose. It will go up further as you are playing too. What an interesting mechanic this is! Yes, your armour will hale to keep you alive on an incursion but you have to spend money to repair and maintain it. Can you afford that? I like it. But after yesterday’s debate, I am definitely getting Valen some nicer stuff.

- Combat Equipment:

- Armour – Breastplate, Helmet

- Weapons – Crossbow, Dagger

So, I guess that increases my Burdens score to 5.

Step 4 – Choose your Rituals, if any

You don’t have to be a wizard or anything to perform these, all treasure hunters can learn and use rituals, dangerous magic that can perform “miraculous feats.” Now, I can have as many as three Rituals to start, but, it says here that, for each one I know, I must increase my starting Ruin by 1. Let’s see what that means, exactly.

Cryptically, the rules describe Ruin as:

“…how much the world has dug its claws into you, including the physical and mental harm you’ve suffered.”

Similar to Burdens, it starts at 1 but, as stated above, it increases commensurate with the number of Rituals known.

I have no experience playing this game so I don’t know the true consequences of choosing to increase my Ruin like this, but for fun, I’m going to take three random Rituals:

- Beacon – nearby invisible beings or hidden objects shine with a fiery glow

- Enliven – give flesh and breath to a human effigy (!)

- Germinate – compel plants to furious growth

This, I suppose, increases my Ruin score to 4.

Finally, set your Ruin, Burdens and Hoard

Easy.

- Ruin: 4

- Burdens: 5

- Hoard: 0 (this number is always 0 at the start.)

Comparison

It’s possibly unfair to compare this experience with that of making the OSE character yesterday since they are based on two such mechanically different games. But that’s what I am going to do.

Over all, I found that the character I created in the Trophy Gold system was never going to be compared negatively, or indeed, positively, to other characters in the same system. And that is purely because it does not rely on numbers so much. You will have noticed that Valen does not have attribute scores or hit points, for instance. Despite this, the Trophy Gold character is just as unique as the OSE character. It’s just that the differences between my ex-soldier/smuggler are more descriptive than numerical.

You will also have noticed that the character creation process encouraged me to think about the character’s background while making my treasure hunter. I don’t remember this ever coming up in the OSE process.

I did a lot of rolling on tables for this process, which I didn’t foresee when I went into it. In fact, I ended up with altogether more on the character sheet than I expected from such a rules-lite system. But I enjoyed the process and found the details provided by the tables fun and interesting.

One aspect that I liked, though, was that I had to choose the Combat Equipment and Rituals. These directly affected my Burdens and Ruin scores. These are the scores that will have the most impact on the way you play the character. I read on a bit and discovered that, if Valen does not come back from his incursion with Gold equal in value to his Burdens score, he’s done… He is left in penury or sent to the workhouse. As good as dead. Not only that, but, if his Ruin ever reaches 6, he is lost to the darkness, transforming into a monstrosity himself, or he is simply dead. Makes my decision to take three Rituals look a bit foolhardy now, eh?

Conclusion

Anyway, as I said, it is not really fair to compare the two systems. One is deliberate in its devotion to the OSR and its historical roots. It made a character that probably won’t last too long but mainly due to luck. The other is more interested in the story the players tell and the narrative beats produced by the characters created. My treasure hunter also probably won’t last long, but this time it is due to my choices.

Dear reader, do you have any experience playing Trophy Gold? How did you like it?

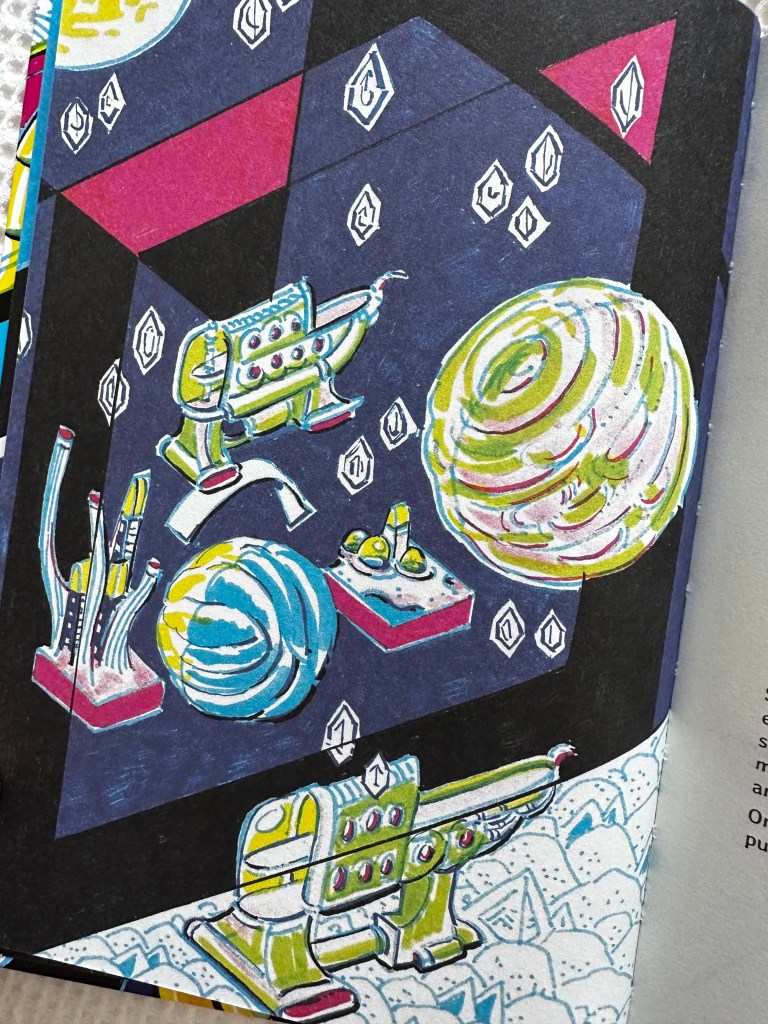

, do yourself a favour and go check them out. When I first encountered his work several years ago, it filed me with wonder. He created such a realistic depiction of a past that was largely recognisable to me from my own childhood, interspersed with or shockingly dominated by futuristic architectures and sci-fi wonders. His work excited my imagination like only RPGs had in the past. So when I discovered that Free League were producing a [Tales From the Loop game](https://freeleaguepublishing.com/games/tales-from-the-loop-rpg/), it didn’t take me long to pick it up. It took a little longer to get it to the table but when I did I discovered that the players loved it.

Tales from the Loop is a game about the 1980s that never was. It posits a world in which some astounding scientific breakthroughs occurred in the ‘50s and ‘60s so that, by the time in which the game is set, they are not considered so strange. You have your robots and your hovercraft and your infinitely renewable energy. But most of that stuff is considered mundane in Stålenhag’s world. Not only that, they exist alongside the ‘80s mainstay technologies like Walkmans, cassette tapes, VCRs and Soda Stream. In Stålenhag’s artwork this created some beautifully uncanny images. Most were set in the region of Sweden known as Mälaröarna, where the Loop project was based. This is where the world’s largest particle accelerator was built. Though it is not necessarily directly responsible for the many strange occurrences in the region, the people who populate such a scientifically rarified place usually are. Scientists and administrators and students flocked to the region and started families there. So many of Stålenhag’s paintings involved kids; a toe-headed child threatening an old Volkswagen van marked “Polis” with a giant robot under his control; a pair of woolly-hatted kids digging in the Swedish snow and gazing back at their homes, dwarfed by the cyclopean, other-worldly cooling towers used to release heat from the core of the Loop itself, the Gravitron; a little kid in cold weather coveralls leading his grandfather through the snow to a mysterious sphere, left abandoned in the countryside, its purpose and provenance forgotten. These were the inspirations for the RPG.

The game came out at the height of the popularity of Stranger Things, which helped it gain a lot of traction I think, and then it even had its own, unfortunately not so popular, spinoff [TV series](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tales_from_the_Loop), which I, at least, loved.

In the RPG you play kids between 10 and 15 years old. You get to choose a Type from such classics as the Computer Geek, the Hick and the Weirdo. You also have to choose some really fun things like your Iconic Item, your key relationships and your favourite 1980s song.

Once you have your Kid, you and your friends can go out and investigate weird shit on your bikes. Stuff like, where are all the birds gone? What are all the adults doing gathered around that weird machine in the field? What’s that dinosaur looking claw print in the snow? You know, normal kid shit.

## Roll mechanics

Tales from the Loop uses a version of the Year Zero engine, and, in fact, it was the first game I played using that system. It’s really straight-forward and intuitive, easy to learn and resolves situations quickly. “Situations” are generally and collectively referred to in the text as “Trouble” with a capital “T,” appropriately enough. For many, the Trouble you got into and out of when they were kids are some of the most enduring and treasured memories. In the game, you combine your ability dice and your skill dice into one dice pool and roll them all to try and get at least one 6. Since you only use d6s in this game, that’s the highest you can roll. The more 6s you roll the better, generally.

The only issue my players and I had with the rules is the Extended Trouble mechanic. The way this works is that, during the final showdown, encounter or whatever, every kid says what they are going to do and the GM tells them how many successes they will need to succeed fully. Then one player rolls all the dice in one enormous pool. Generally, if they don’t succeed fully but they still have a few successes, they might achieve what they were trying to but one or more kids will earn conditions or even become Broken. But, in play, we found this approach to be unsatisfying. Each player wanted their own cool moment to roll for and the all-or-nothing approach meant that they couldn’t attempt to take any rectifying actions if and when they saw things going wrong. Anyway, suffice it to say, we won’t be using the Extended Trouble rule next time.

## Mascots and Murder

Here are the very basics of the scenario I have planned:

Although the first Loop was in Sweden and much of the book is written as though it is the default setting, they do actually provide a second potential setting in it. That’s Boulder City, Nevada, the “Best city by a dam site,” which is a reference to its proximity to the Hoover Dam. There is another Loop in this region and all of the scenarios presented in the core book can be transposed very easily to the desert, believe it or not. This is where the kids in this scenario will be from. It is summer in Boulder City so it’s going to be so sizzling hot that you can fry an egg on the sidewalk. This will be a nice change as all the other Tales from the Loop games I have played were set in Sweden in autumn and winter.

Some teens have gone missing from Boulder City. Although their parents don’t seem too worried about it, our intrepid Kids are going to solve this mystery as they track down the source of the eerie, carnival-like music out in the Nevada desert and figure out what the connection is.

I have had fun writing this scenario, even though I have gone over it and over it to get it right. So, it’ll be ready to play in a few weeks.

The Tales from the Loop core book has some very useful advice for writing and structuring a scenario for it yourself. As long as you stick to that, you’re unlikely to go wrong. This is not actually the first one I have written myself, using these guidelines and, I can tell you, it works really well.

Have you played Tales from the Loop? What did you think of it? If you had to run a particular game for Indie Mascot Horror vibes, what would it be?](https://thedicepool.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/img_3376.jpeg?w=1024)

, do yourself a favour and go check them out. When I first encountered his work several years ago, it filed me with wonder. He created such a realistic depiction of a past that was largely recognisable to me from my own childhood, interspersed with or shockingly dominated by futuristic architectures and sci-fi wonders. His work excited my imagination like only RPGs had in the past. So when I discovered that Free League were producing a [Tales From the Loop game](https://freeleaguepublishing.com/games/tales-from-the-loop-rpg/), it didn’t take me long to pick it up. It took a little longer to get it to the table but when I did I discovered that the players loved it.

Tales from the Loop is a game about the 1980s that never was. It posits a world in which some astounding scientific breakthroughs occurred in the ‘50s and ‘60s so that, by the time in which the game is set, they are not considered so strange. You have your robots and your hovercraft and your infinitely renewable energy. But most of that stuff is considered mundane in Stålenhag’s world. Not only that, they exist alongside the ‘80s mainstay technologies like Walkmans, cassette tapes, VCRs and Soda Stream. In Stålenhag’s artwork this created some beautifully uncanny images. Most were set in the region of Sweden known as Mälaröarna, where the Loop project was based. This is where the world’s largest particle accelerator was built. Though it is not necessarily directly responsible for the many strange occurrences in the region, the people who populate such a scientifically rarified place usually are. Scientists and administrators and students flocked to the region and started families there. So many of Stålenhag’s paintings involved kids; a toe-headed child threatening an old Volkswagen van marked “Polis” with a giant robot under his control; a pair of woolly-hatted kids digging in the Swedish snow and gazing back at their homes, dwarfed by the cyclopean, other-worldly cooling towers used to release heat from the core of the Loop itself, the Gravitron; a little kid in cold weather coveralls leading his grandfather through the snow to a mysterious sphere, left abandoned in the countryside, its purpose and provenance forgotten. These were the inspirations for the RPG.

The game came out at the height of the popularity of Stranger Things, which helped it gain a lot of traction I think, and then it even had its own, unfortunately not so popular, spinoff [TV series](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tales_from_the_Loop), which I, at least, loved.

In the RPG you play kids between 10 and 15 years old. You get to choose a Type from such classics as the Computer Geek, the Hick and the Weirdo. You also have to choose some really fun things like your Iconic Item, your key relationships and your favourite 1980s song.

Once you have your Kid, you and your friends can go out and investigate weird shit on your bikes. Stuff like, where are all the birds gone? What are all the adults doing gathered around that weird machine in the field? What’s that dinosaur looking claw print in the snow? You know, normal kid shit.

## Roll mechanics

Tales from the Loop uses a version of the Year Zero engine, and, in fact, it was the first game I played using that system. It’s really straight-forward and intuitive, easy to learn and resolves situations quickly. “Situations” are generally and collectively referred to in the text as “Trouble” with a capital “T,” appropriately enough. For many, the Trouble you got into and out of when they were kids are some of the most enduring and treasured memories. In the game, you combine your ability dice and your skill dice into one dice pool and roll them all to try and get at least one 6. Since you only use d6s in this game, that’s the highest you can roll. The more 6s you roll the better, generally.

The only issue my players and I had with the rules is the Extended Trouble mechanic. The way this works is that, during the final showdown, encounter or whatever, every kid says what they are going to do and the GM tells them how many successes they will need to succeed fully. Then one player rolls all the dice in one enormous pool. Generally, if they don’t succeed fully but they still have a few successes, they might achieve what they were trying to but one or more kids will earn conditions or even become Broken. But, in play, we found this approach to be unsatisfying. Each player wanted their own cool moment to roll for and the all-or-nothing approach meant that they couldn’t attempt to take any rectifying actions if and when they saw things going wrong. Anyway, suffice it to say, we won’t be using the Extended Trouble rule next time.

## Mascots and Murder

Here are the very basics of the scenario I have planned:

Although the first Loop was in Sweden and much of the book is written as though it is the default setting, they do actually provide a second potential setting in it. That’s Boulder City, Nevada, the “Best city by a dam site,” which is a reference to its proximity to the Hoover Dam. There is another Loop in this region and all of the scenarios presented in the core book can be transposed very easily to the desert, believe it or not. This is where the kids in this scenario will be from. It is summer in Boulder City so it’s going to be so sizzling hot that you can fry an egg on the sidewalk. This will be a nice change as all the other Tales from the Loop games I have played were set in Sweden in autumn and winter.

Some teens have gone missing from Boulder City. Although their parents don’t seem too worried about it, our intrepid Kids are going to solve this mystery as they track down the source of the eerie, carnival-like music out in the Nevada desert and figure out what the connection is.

I have had fun writing this scenario, even though I have gone over it and over it to get it right. So, it’ll be ready to play in a few weeks.

The Tales from the Loop core book has some very useful advice for writing and structuring a scenario for it yourself. As long as you stick to that, you’re unlikely to go wrong. This is not actually the first one I have written myself, using these guidelines and, I can tell you, it works really well.

Have you played Tales from the Loop? What did you think of it? If you had to run a particular game for Indie Mascot Horror vibes, what would it be?](https://thedicepool.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/img_3375.jpeg?w=1024)