It Begins!

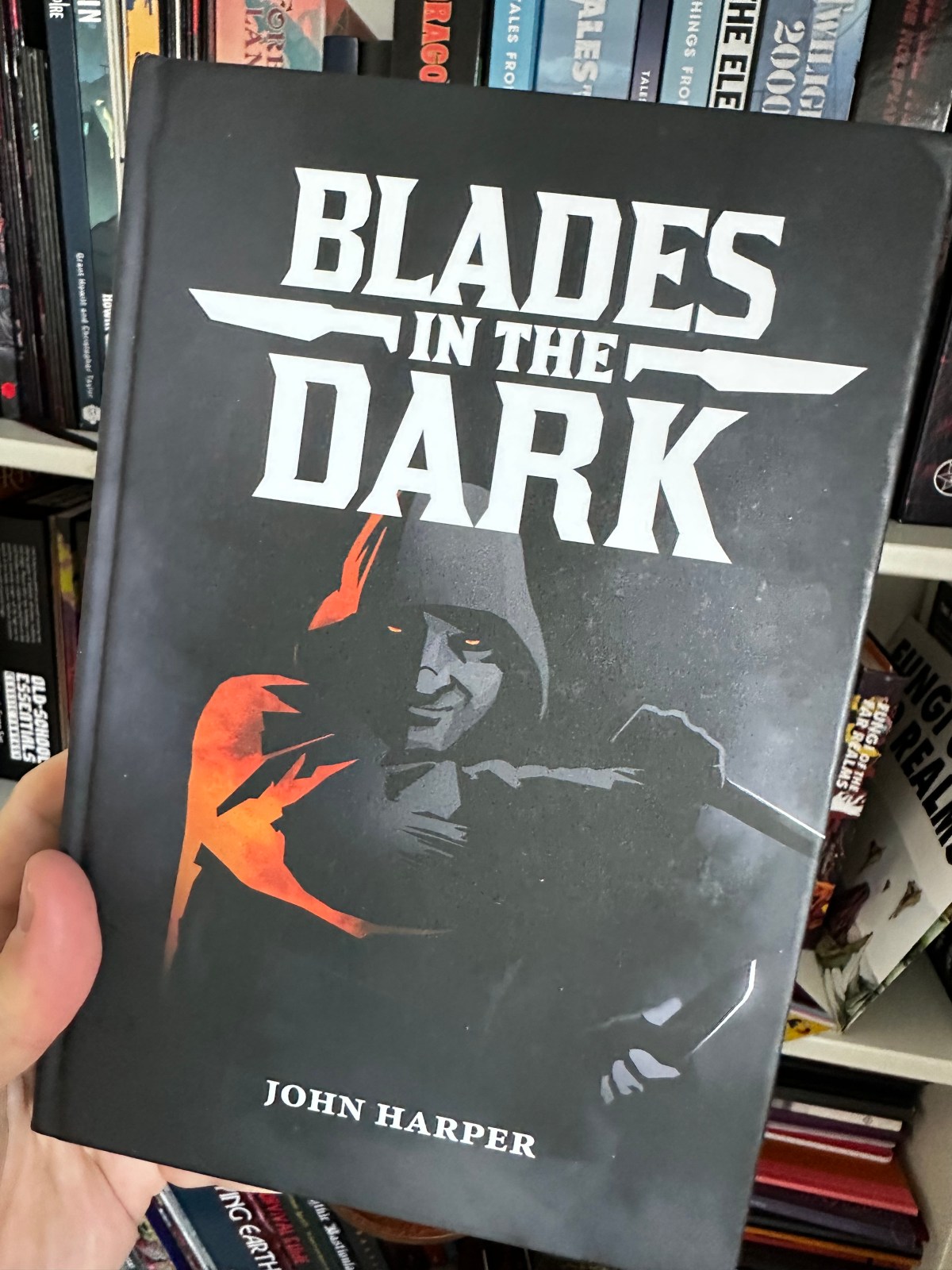

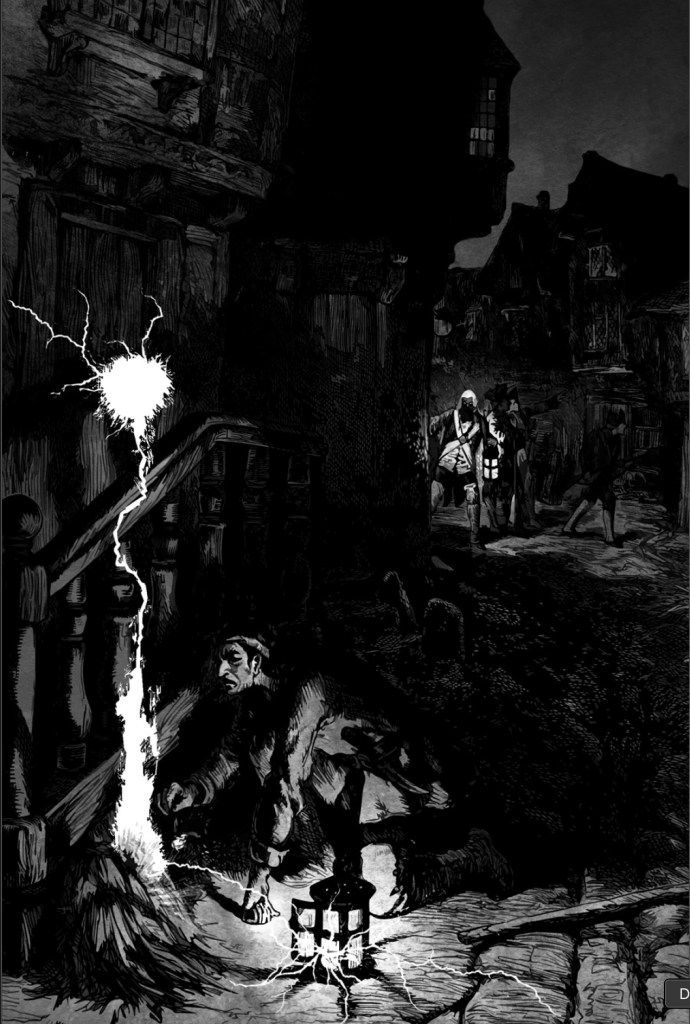

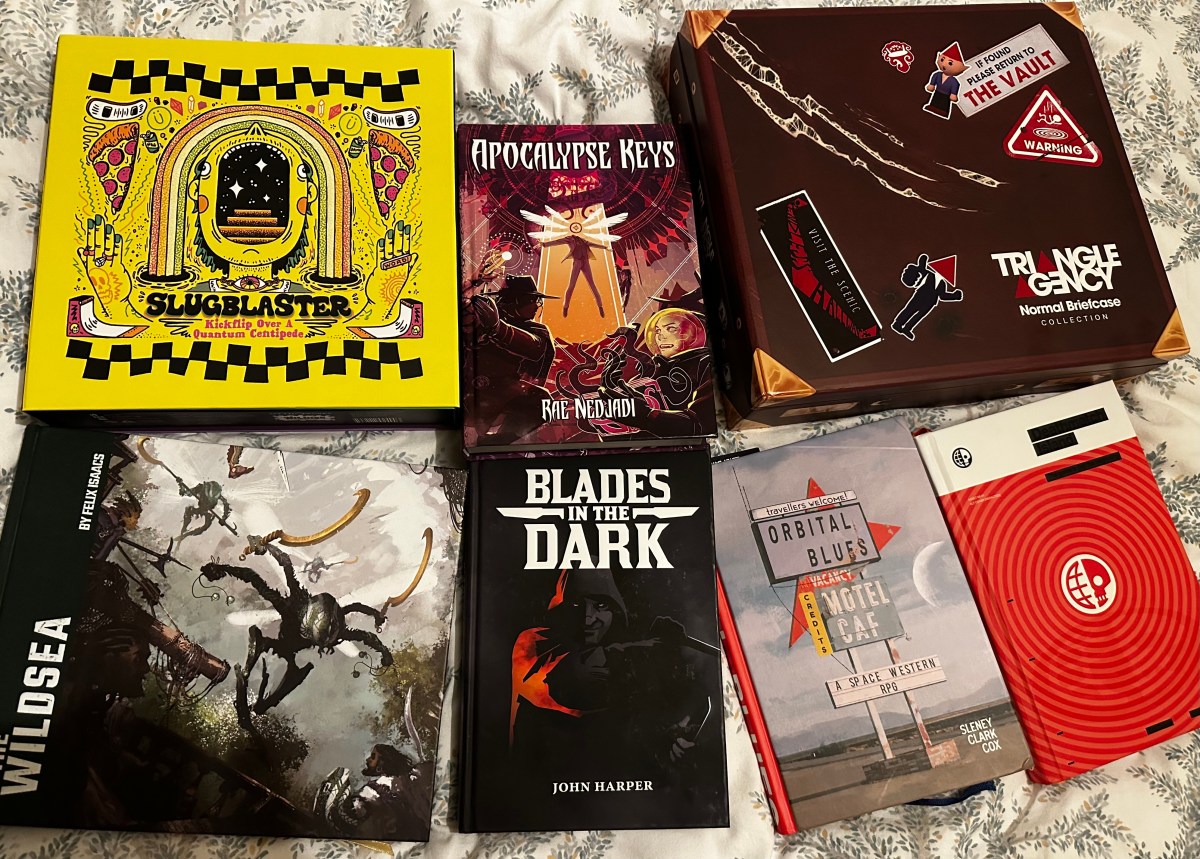

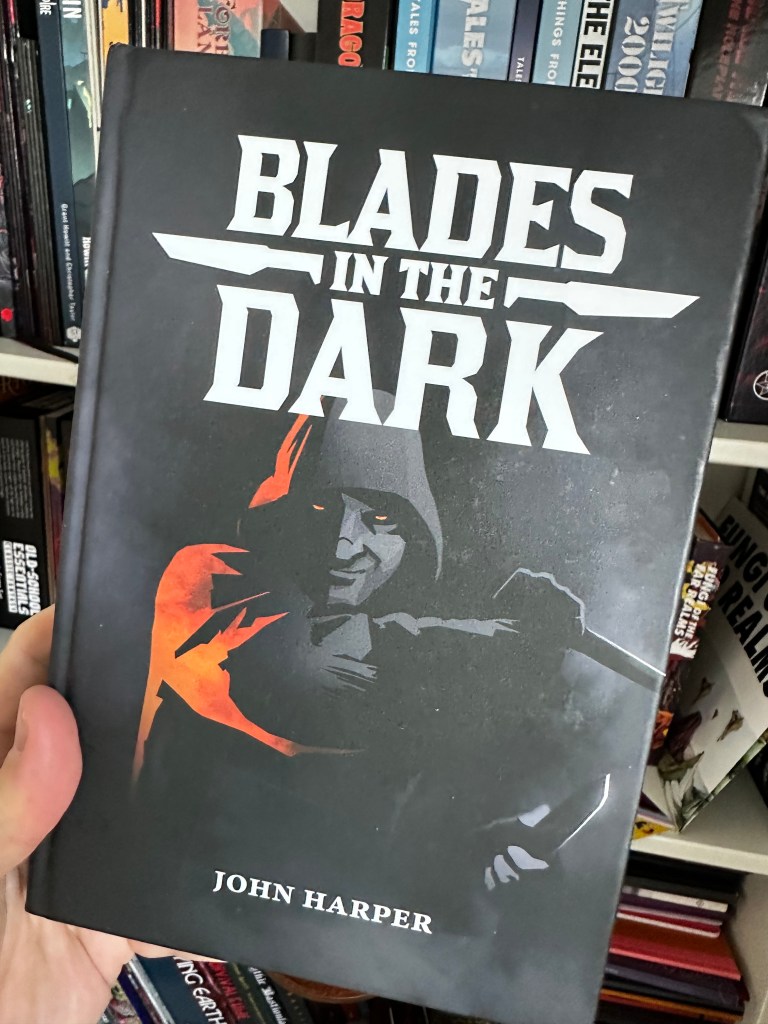

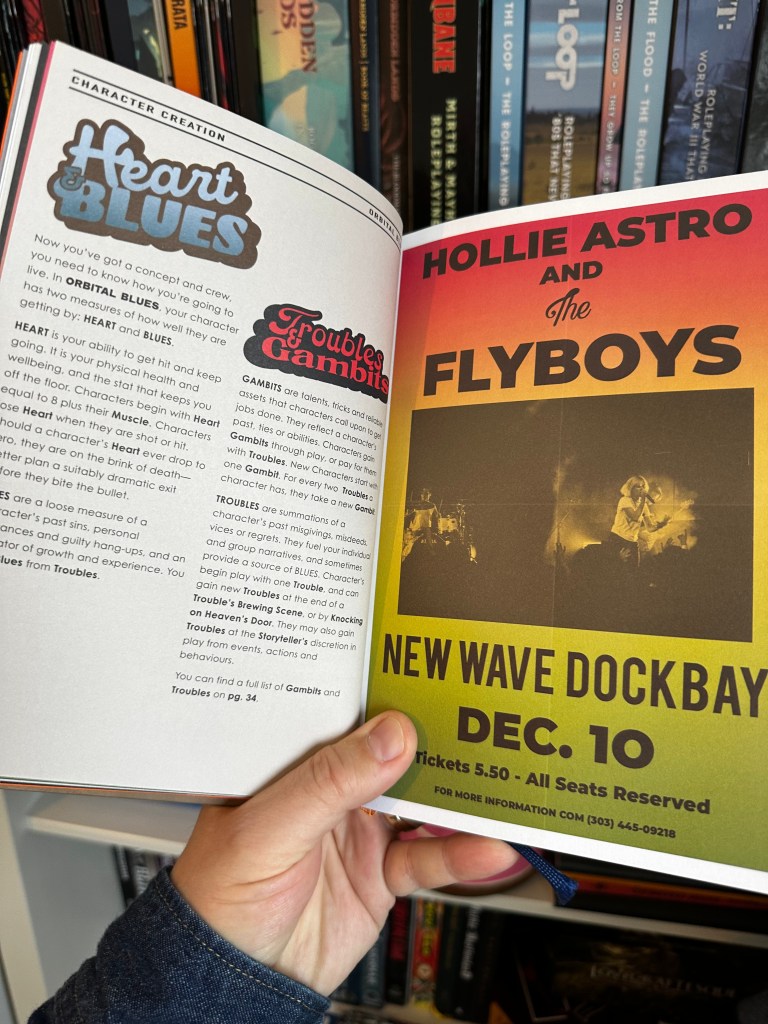

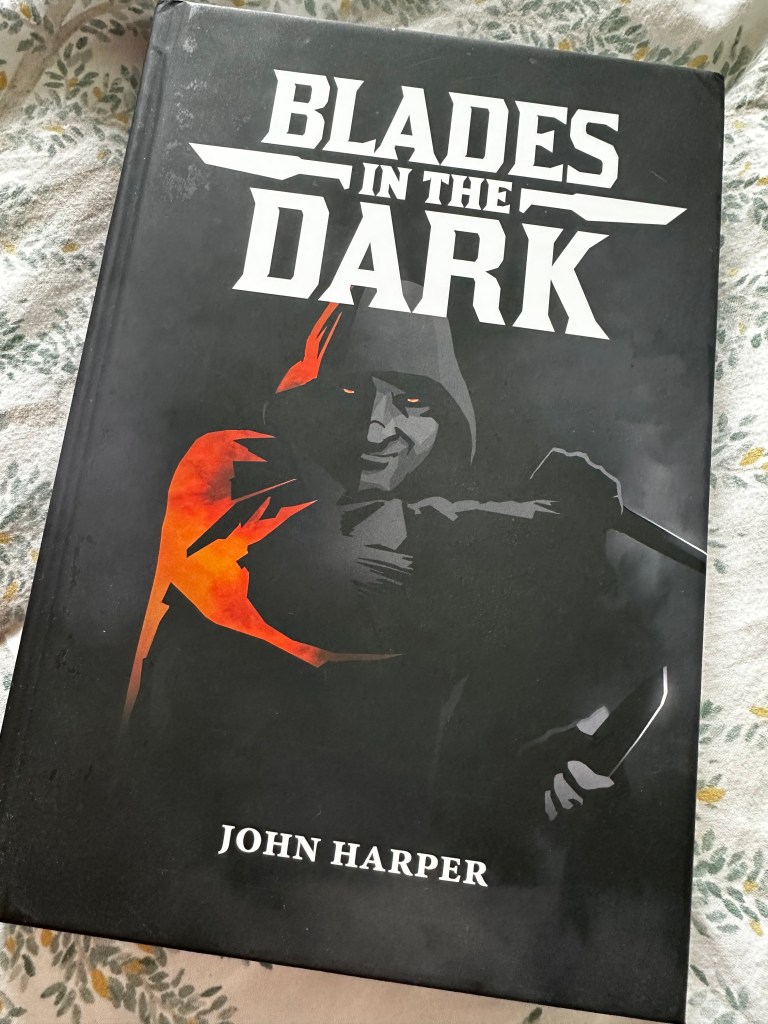

Our Blades in the Dark campaign starts tonight! I’m excited. I played in a campaign before but this will be my first time GMing one. I’ve been taking a look at the GM advice presented in the book over the last few weeks. This post examines the GM toolkit in the Running the Game chapter, and this one looks at John Harper’s advice for Starting the Game. Right before starting seems like a good time to internalise the Best Practices espoused by the same chapter of Blades in the Dark, and to beware of the Bad Habits!

Best Practices

We’ve got a list of fourteen best practices for GMs here. Although I’m sure these were written very much with Blades in mind, most of them feel like the kinds of things a GM is well advised to utilise while running a lot of different RPGs. Just take a look at the list:

- Earn the trust of the group

- Lead an interesting conversation

- Create an atmosphere of inquiry at the table

- Help the players use the game system

- Don’t block

- Keep the meta channel open

- Be a curious explorer of the game in play

- Advocate for the interests and capabilities of the NPCs

- Play Goal-Forward

- Cut to the Action

- Be aware of potential fiction vs. established fiction

- Zoom the action in and out

- Bring the elements of the game system to life on screen

- Put it on a card

As in the last Blades post, I’m not going to go into each and every point in detail. Some of them are self explanatory. Put it on a card, for instance means exactly what it sounds like: use index cards to record the important things that are invented at the table. Cut to the Action is doing double-duty as both a GM principle and a best practice. You’ll find it listed in the last Blades post too. Keep the meta-channel open means that you, of necessity, have to describe the subtext to the players sometimes, to represent their characters’ full range of senses and intuitions and the like. Help the players with the game system, equally, means it’s your job to interpret their words and plans into a form the mechanics can handle without forcing them to figure it out themselves.

Anyway, you get the idea. I want to take a few that interest me the most and discuss them.

Be a curious explorer of the game in play

Just take a moment to digest that sentence. “A curious explorer.” Isn’t that sumptuous? There aren’t a lot of RPG books out there creating phrases as attractive as that, and I would like us to all appreciate John Harper’s work on it. As pleasing as the phrase is, the sentiment is truly important. Look, you’re the GM; you’d better be paying attention to what the PCs are doing, to what the players are saying at the table, to the NPCs that are being dicked over, or seduced or fucking created during a session, or they’ll come back to bite you in the arse later. But that’s not what this practice means. It just wants you to maintain a degree of curiosity in the events of the game, not because they are important, but because they are fun and interesting. Look up from your notes and index cards every once in a while and breathe it in. Your players and you are building an incredible story together. This is what it’s all about. So, get interested. Ask questions, not because you want to know stuff to prepare for but just because you are curious. Maybe you’ll wonder aloud why a PC is doing something, maybe your curiosity is to do with their choice of decor for the lair, maybe its just because they gave that one NPC a stupid nickname and you don’t know why. Doesn’t matter, just stay interested.

Play Goal-Forward

This is the practical side of the question-coin. It’s nice to think this game is all about the players after the initial stages. The idea is to get them to form their own ambitions for characters and crew, come up with their own scores, fulfilling their own whims and get into and out of their own trouble. But, if my experience as a GM is anything to go by, this can take a little cajoling. So, this practice says, lead that conversation. Get them thinking about their goals, not just in the moment, on the score, during their downtime, whenever, but also, on a long-term, grand scale. Yes, you need to know what their goal is when things begin to turn to shit on a score, they’re up to their ears in ghosts, the Bluecoats want their blood or their lair was just blown up by the Lampblacks. But if you get the players to tell you what they really want to be when they grow up? That’s gold. And make sure you check in to find out if their ambitions have changed from becoming the greatest electroplasm smugglers Duskwall has ever seen to just base survival because every score they have attempted has gone south and enemies are at the gates.

The pursuit of opportunities and positions to enable certain approaches, the acquisition of information and resources, and the nested conflicts that result will drive the action of the game.

This is what you want to get to. If you understand the opportunities they want to pursue, the actions they might take to unlock them, then you can better facilitate them and the effects will help build the game.

Harper repeatedly refers to the game as a cool tv show that you’re invested in. You can be invested in what happens to the characters and the city from the viewpoint of the audience but you are also in the enviable position of being able to help shape the story as a showrunner.

Be aware of potential fiction vs. established fiction

You’re not taking the PCs on a tour of every room of your house. The PCs should be more like viewers watching an edited sequence of shots that carry them forward in the action of the game

We’re still talking about the game as a tv show then. Cool. I like it. It’s a little confusing, though, that this practice is about keeping details of the fiction nebulous until they need to be concrete. I suppose a good way to continue the analogy is to say that we begin a scene with a close-up on the darkly wrapped faces of our scoundrels, and, as the players ask questions or the GM makes decisions, the camera pulls away, revealing the canal-side they are standing on, then further out to show the line of moored canal boats. Then we follow the crew across the decks of the gathered boats as they rock and the occupants cry out. As they go, the players might ask if there is any rope on the decks to allow them to climb on to the bridge and you tell them there is. Meanwhile you fill in some more details, the twitching of curtains in the surrounding windows, the scuffling of feet from the nearby alleys and so on. Layers and layers of details. Harper calls this the potential fiction cloud. You pick them out as you build the scene and they gain concreteness, they become the established fiction. But you never need to establish absolutely everything. Instead, you yell “CUT,” and move on to the next scene, starting over again with a new potential fiction cloud.

GM Bad Habits

The bad habits that are listed here are fewer in number but oh so much greater in the size and capitalisation of their headings:

- DON’T CALL FOR A SPECIFIC ACTION ROLL

- DON’T MAKE THE PCS LOOK INCOMPETENT

- DON’T OVERCOMPLICATE THINGS

- DON’T LET PLANNING GET OUT OF HAND

- DON’T HOLD BACK ON WHAT THEY EARN

- DON’T SAY NO

- DON’T ROLL TWICE FOR THE SAME THING

- DON’T GET CAUGHT UP IN MINUTIA

It is hard to avoid the conclusion that it is more important to ensure you don’t develop these bad habits than it is that you adhere to the best practices above. Let’s look at a few that I think I might be most susceptible to and see if that’s true.

DON’T OVERCOMPLICATE THINGS

It’s a heist. Or maybe an assassination attempt. Possibly a smuggling operation. There should be complexities to it! There should be bribes and double-crosses and traps and security systems and hidden lookouts and maybe a jilted lover or two. Right? Not necessarily. Its fun to introduce new narrative complications and consequences on a 1-3 or a 4/5 roll, of course, but not at the expense of the session’s pacing, or the players’ patience. You can’t be expected to come up with that stuff all the time. There are mechanics in place to help you deal with them quickly and in keeping with the spirit of the game. So this section is telling you to use the tools you have been given. If you can’t think of a new complication, just hit them with harm or tick a clock forward or slap some more HEAT on them. Keep it simple, stupid!

DON’T HOLD BACK ON WHAT THEY EARN

I have the potential to be stingy. After all, there is a lot they can do with Coin in Blades in the Dark. You can use it improve Downtime Projects, to reduce HEAT, to advance Crew Tiers! I could be the kind of GM who wants to limit their progress, to slow the pace. But John Harper says give them the money. He wants us to remember that they should get what they earned. After all, they have it hard enough as it is. And besides, they’re likely to have to spend it before it even has a chance to enrich their pockets.

My main observation here is that, in all likelihood, the GM is the one setting the Coin value of any given score. The PCs, of course, are free to accept or reject opportunities depending on how lucrative they are, and they will have to take the heightened risk associated with bigger paydays, but still, its up to the GM, in many ways to establish how much a given sort of score is worth. If I wanted a low scoring campaign, I could start off with big scores netting no more than 4 Coins and most average ones paying only 1 or 2. Of course the opposite is true too. And I guess Mr Harper wants us to lean that way.

I appreciate more the admonition to treat secrets and information the same way. If the PCs have earned the info, don’t hold back. Only new opportunities and a deeper investment in the world on the part of the players can come from the sharing of secrets. Bring them in on it! They’ll love it.

DON’T GET CAUGHT UP IN MINUTIA

Let’s keep thinking about this in terms of a television show. Sure, there might be some shows where an eye for detail and a quick thumb hovering over the pause button is rewarded, but usually, you can rely on directors/editors to skip from one location and situation to another without the need to dwell on every twist and turn on the way. Get to the good stuff. Speed through the opening credits, jump to the negotiation or the shoot-out or the incursion into the ghost field.

Although it’s not mentioned here, I believe it’s also important to combine this warning with the lesson to be aware of potential vs. established fiction. You want to try and hit that sweet spot where you have given the players enough details of a location, person or scene to allow them to make decisions without getting bogged down in unnecessary levels of photo-realism. Allow the imaginations of the players to fill in the blanks instead.

Conclusion

Look, it’s pretty obvious that if you occasionally forget to be a curious explorer of the game or sometimes stray into the weeds in describing minutiae, you’re not going to break your campaign. But it sure is nice to have these guide-rails to help us make the best damn dark victorian horror heist game we can! Both lists are incredibly useful and I’m sure to be referring back to them every once in a while as the campaign gets under way.

Next time

In my next Blades post I’m going to do a sort of post-mortem of our very first session! Watch this space, dear reader.