Link

I realise I should have been sharing a link to all the previous chapters of the Apprentice at the start of each new one. So, I will start doing that today, Here it is:

The Apprentice Chapters

I won’t go on in the introduction this time as it is a long instalment. Let’s get into it:

Chapter 5: Mistress Aggie

Even before we left my world behind at the farm I knew I wanted to know things. At first, almost anything would do: wildlife lore; plant lore; astronomy; languages; money; weather; medicine; gambling; food and cooking; anything, as I said.

My father taught me what he could but his lack of education was an obvious stumbling block. He taught himself to read and write, though his handwriting was abominable and barely legible and he had no feel for spelling. Still, what he knew in this regard, he helped me to learn. I had surpassed his reading and writing abilities by the time I was seven years old although there was precious little to practice on. Most of the time, when I wanted to write something I would choose a dried up patch of mud out in the farmyard and make my marks with a sharpened stick or the end of a farming implement of some kind. The next rain would wash it away but the mere act of writing would always help me to illustrate a problem for myself and to solve it or simply to memorise a thing. As I scraped a verse or a formula or a passage of prose into the ground, it was scraped also into my memory forever. The memorisation of more private things would take me up to the mud in the western field where I would use my stick or pitchfork to scribble. Once I had written my private meanderings or recorded my feelings in the glutinous mess of earth and water and sheep-shit I would just walk through it in my bare feet and erase it for good now that it was etched on my mind.

Eventually, father noticed my dirt scribbles and perhaps thought that that was no proper use for a farmyard. As a result he fashioned me a chalkboard by fixing some old pieces of rubbish wood to the edges of a roof slate. To write on it, I was told, I would have to venture down to the quarry on the eastern edge of the farm and wrest some chalk from it. I dutifully did as I was bid and brought back from the quarry a basket full of crumbling chalk blocks. It had been lying around on the floor of the old quarry and was yellow and brown in patches and had scraggles of dirt and grass attached to it in many places. It was the best present my father had ever given me, even though he had made me fetch half of it myself and the chalk broke so quickly and produced a choking cloud of dust once dried and used. I went to the quarry after that to scavenge hunks of chalk whenever I needed them, which was often. I could finally jot and scribble and work at my leisure in and out of the house. My sister made fun of my writing and complained of the chalk-dust constantly but it made no difference to me, I already knew she hated me at that point and I realised she was but jealous of my intelligence and knowledge.

I had learned a lot and memorised a lot in this way, I had even taught myself many of the natural laws that I would later read of in old tomes and new treatises, though, perhaps, I did not have quite the vocabulary necessary to record them as the sages did. I made up for that later in life. I wrote volumes later in my life on all subjects from the most efficacious practices in agriculture to the most terrible spells of the occult. Had I led a different sort of life I would have been a famous sage, advisor to kings or provost of a university perhaps. My fame was not to be derived in such mean and mundane pursuits though…I am getting too far ahead of myself now. I must rein in my errant thoughts and focus on the tale and task at hand.

There was, of course, a whole world outside my world of which I knew absolutely nothing. While back on the farm I could progress no further. I had not books nor teachers nor knowledgeable company of any kind. I often wondered if the most well educated being in my life other than myself was the owl, which I often heard hoo-hooing outside my window at night as it hunted around the barn and the great oak which gnarled its way around the east and north sides of our farmhouse. I discovered this was not the case when one night I saw the owl caught in a net after it was fooled by a fake mouse on the ground in the Markinson’s yard. I remember weeping that the evil and thick-headed young Markinson boys should trap and keep the owl as a pet. Soon, I realised that if the bird was stupid enough to be snared by a Markinson then it deserved to be caged.

Not long after this incident we were forced to move from the farm, Greysteel was made bird-feed, father left and Primula and I were lumped on old Mrs Blanintzi. All of these things seemed terrible to me but soon I determined that it was not such a heinous fate after all. For I was in a town. I had not dreamt that there could be advantages to this. I had never considered that wise people made their homes in towns because there were other, not so wise people in towns who always seemed to need advice or mechanisms or tinctures or money or even, in the most extreme circumstances, magic. Real magic was not what most of these idiots wanted but the kind that fooled them into believing in wishes and good fairies and healing touches and love. I could see that most of the folks who claimed to be purveyors of such powerful magicks were nothing more than charlatans. Still, I admired them for the way they took advantage of those who were easily parted from their silver crowns. I had little interest in learning their ways, though. There were two people only in the town from whom I desired knowledge but they had no notion of imparting their hard-won secrets to the likes of me, I am sure, even had they known I existed.

Old Aggie, as you will, no doubt, recall was called Old Aggie even on the fateful day of my birth, now almost nine years previous. She was, as you might also recall, a “mad, old biddy,” as my sister so eloquently put it. But I had seen things that you would not believe, feats performed by Old Aggie that would have been described as unnatural and blasphemous by the stupid and pious of the town.

Once, I crept out my bedroom window at extreme personal risk. My room was on the second floor and its window accessed the ground only by a poorly maintained and rusting drainpipe. I did this foolish thing and survived it in order to go and spy on the “Wise-woman” (this was the euphemism applied to Aggie in her presence. Everyone obviously just called her “The Witch” when she wasn’t within earshot.) This was more difficult an adventure than I had anticipated. Old Aggie resided in a dilapidated pig-shit and wattle hovel on the edge of town and the edge of a tanner’s pit. The stench was close to unbearable, I remember. I came close to fainting away on two occasions as I attempted to hold my breath (I find this quite amusing now considering the olfactory calumnies I would be subjected to in my later life.) Her windows were tiny portholes placed high on the wall even though the place was, of necessity, a one floor affair. I was short. Even for a boy of almost nine, I was considered improperly short (is there no end to the ignominies of my existence?) so I was forced to find something to stand upon to see through her window into the torch lit space beyond. It was pitch dark outside the house so I felt about me and connected with something more or less solid that seemed about the right height for me to stand upon. It felt, I recall, as though it were perhaps a lichen-covered wooden frame of some kind. It was solid but slippery to the touch. I dragged it just below the window and climbed atop it to spy on the Witch.

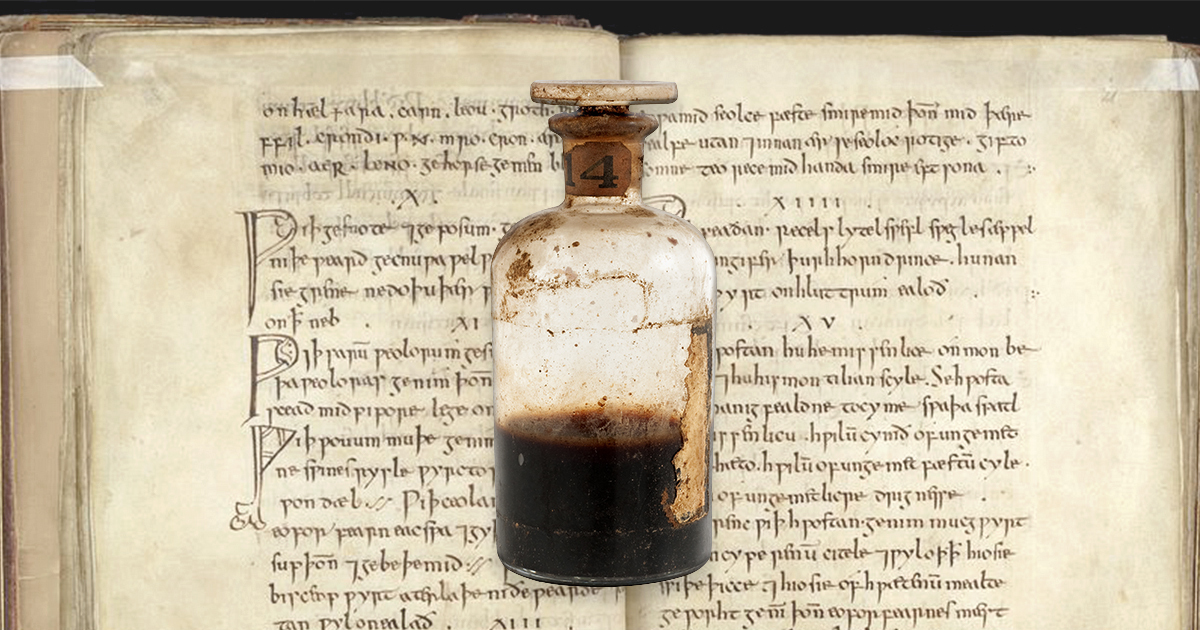

A museum of the grotesque I always felt was a good title for Old Aggie’s house. Every inch of spare floor and wall was occupied by a basket, jar, phial, bottle, amphora, tank, sack or pouch of something. I would never discover what most of them contained but I could see clearly enough what the glass vessels had in them. There were homunculi; deformed, two-headed, horned, broken creatures (of course, now, I know that they were the formaldehyde pickled aborted foetuses from ashamed or deceased mothers. At the time, though, they seemed to me to be goblin children or perhaps deformed fairies. The uses she found for them would one day repel me and force me to abandon her as a mistress.) One contained black liquid with a hint of crimson when the torchlight played on it. I assumed this to be blood, though, it’s provenance, I could not have guessed at. Another trapped a clear liquid which I immediately took to be the tears of my father (in this assumption I was correct. How she had managed to prevent them from evaporating, I am not certain. It is a magic I was never made privy to or else the magical properties of the fresh tears of a widowed father preserved them. It is not important now, anyway.) There was dung, fangberries, elephant’s tail seaweed, a quart of an unidentified white fluid, live wasps, a grass-snake, fermented beans, half a brain (possibly human,) no fewer than twelve pairs of disembodied testicles and a number of other internal organs which, at the time, I possessed not the education to allow me to identify. Some of the more opaque containers moved of their own accord and one of them was animated all about its rim with the popping bubbles of some black liquid I took to be tar but might just as well have been demon’s blood. The smoke-blackened ceiling with its chimney-hole in the centre was festooned all about with skins of mammal and reptile, ruined nets, sticks of varying length and girth, giant black and grey feathers, bloodied rags and seemingly ancient cobwebs.

Old Aggie herself must have taken her rest on furs and blankets on the minuscule patch of clear floor space in the centre of the one-roomed hut.

Right now, however, she was not sleeping. Her eyes were shut in a dreamy, heavy-lidded, trance-like way and she swayed side to side, forwards and backwards to no particular rhythm but as if she were standing, chest deep, in the water of a gently lapping lake. Even her filth-matted hair seemed to drift weightlessly in the stinking air of her home. As odd as these facts may seem they were not what instantly caught my attention in this scene: she was bare from pate to sole. The sight, I will not deny it, came close to making me retch, what with the sensory hurricane to which I was already being subjected. I controlled myself, however, and my rebellious digestive system, so as to avoid the attention of my erstwhile subject. Although she was unclothed, she was covered by something: something which resembled a mixture of horse-shit and blue paint. My nose was so assaulted by the tanner’s pit that it was of no use in identifying the concoction she was wearing. Aggie was moaning, a low monotonous tone. She did this without moving her lips in the slightest. In the benighted back of the hut a bird squawked, the noise of it becoming louder and, to my ears, more insistent as the moaning continued.

As I watched I could see something happening to the air above the great clay jar over which Old Aggie stood; it became illuminated, gently at first but brighter and brighter as, gradually, the witch’s moaning rose in pitch and speed and volume. The bird’s squawking was now quite fevered and desperate too. And then it was finished. Aggie fell silent, the unidentified bird ceased carking, and the illumination from the jar’s mouth disappeared. Then, I watched in astonishment as the jar rocked a little, scraping its bottom on the dirty clay floor, before it expectorated from its belly a monkey. A monkey emerged from the jar. An orange furred, pug-nosed, eighteen inch tall monkey was now sitting on the edge of the clay jar which had just given birth to it. It looked up, adoringly, at the gnarled and naked witch. She simply said, “You’re here to help me, Monkey, eh? You’ll help Old Aggie with whatever she needs, won’t you?” The monkey did not reply (I had fully expected it to also have been blessed with the power of speech given, normally, only to us lucky humans. I could not have been any more surprised than I already was.) but he did wave his hands and waggle his fingers at the old woman. “No, I don’t think so. I go naming you and before you know it, you’ll have gone and freed yourself and made all sorts of trouble for me, no doubt. I know all your little tricks, and don’t you forget it.” Mercifully, Aggie dressed as she spoke, throwing an old robe over the blue shit on her skin. “Now, fetch me my slippers, they’re over yonder there, under the box with the thing in it.” The newly conjured monkey scampered off to the far corner of the hut and I heard a rattle and squawk from the bird but could see nothing. I tried peering around the window frame but still could make nothing out. “No, no, not that thing the other th-” Then, I crashed with a crack and a slip through my impromptu step and found myself, very quickly, in a fleshy, stinking, rotting nightmare. When I opened my eyes after the fall, I found myself, like a common lung or heart, trapped in a cow’s ribcage and, of course, I screamed. I remember that scream as having been shrill and piercing, like that of a small girl. Aggie came hobbling out, Monkey in tow. “What are you up to there, hiding in that there cow’s chest? What?” So, that’s how I met the first of my teachers.

Aggie, as a teacher, left one wanting. Her ways were her ways and she was desperately set in them. She would always do a full circle of her house before she ever entered it, even in the most inclement of weather. She always woke before dawn and prepared herself a single fried egg and ate it on a piece of dry, white toast. As far as I could tell she never then ate another thing until well after the sun had gone down. She was incredibly messy but always knew where she had put everything and she flat out refused to learn to read and write. She actually said to me once when I offered to show her how to write, “Why are you trying to steal my spirit? Your spirit leaks out of your writing hand and into the those damned squiggles you draw.”

For the first couple of years my illicit visits to the Wise Woman’s home led to me being just as much the helper monkey as the helper monkey was. It was, “Maryk, fetch me water from the well, I need it to make some grub soup (which was exactly what it sounded like,) “Maryk, I need a sparrow’s egg. Didn’t I see some nesting in the eaves of your house?” (I broke my arm that time,) “Maryk, I spotted a pair of pig’s trotters in the tanner’s pit. I need them. Fetch them out of there, will you? Good lad.” (I puked all the way down the side of the pit and all the way back up it again.) I had my own chores to do in my own house. Why would I want to go to her house to do more? I said as much to her one day so she told me to leave. I was back the next morning with my sleeves rolled up and she took me back. “Why?” you ask. Well, even, you see, if I only saw the witch perform a minor cantrip or she taught me one of the basic building blocks of the natural magic that she practised or told me of one of the world’s magical beasts, it was worth every hour of chores. I was learning magic. I was able to perform a couple of insignificant but impressive tricks. I was becoming a magician.

As I mentioned, these visits were unsanctioned. Mrs Blanintzi saw me conversing with Aggie on our square one evening before dark. Later, she said to me at the dinner table, “You know, don’t you, what that Aggie is? You know what she is and you know what she does, eh? I heard that she once destroyed the mayor’s dog and that she used a spell to make young Lena Hedtzi run off on her husband. She is evil, boy and is not fit company for a lad from a respectable family.” It was the first I had heard that we were known as a respectable family but it was not the first time I had heard of these accusations thrown at the feet of my magic mistress. Aggie had explained both of these incidents to me. First, the mayor destroyed his own dog one night when he had drunk so much wine that he fell unconscious in the middle of a dance step, fell and flattened poor Lucky (a misnomer if ever I heard one.) Second, Lena had been beaten so badly and so often by her abusive and ignorant spouse that she had been left with no choice but to take her baby daughter and move somewhere far away. Aggie had had nothing to do with either incident but the majority of human failings are more palatable for folks when they can attribute them to witches. “Its an important public service that we provide!” Aggie used to often say (I later discovered that she was not totally blameless, though.)

So, I was left with no choice but to sneak off to see her whenever I was able. This was difficult because our governess had her eye planted firmly on me at almost all times. I had to escape very often from the town’s school. I hated the school, I had few friends there and the teachers were generally more ignorant than the students. Fortunately the teacher for my class was Mr Schpugelmann, a moustachioed foreigner with a gambling addiction so pronounced that it generally led to him missing more days of school than I did.

I picked it up quickly, magic. Old Aggie said so. She said that I picked it up much quicker than she had and she had been even younger than me when she started to learn at the foot of her mother. Aggie’s mother was still remembered in the Pitch Springs area for having poisoned the water on the Raventzi Farm, stopped the heart in the chest of the high priest in the temple and murdered a whole classroom of children in a terrible explosion. Aggie had loved her mother dearly and still spoke about her whenever I would listen. Sometimes I even enjoyed her stories. Mostly, when I went to the hut, I was impatient to learn something new and never really listened to the rambling of the mad old biddy until I heard the sound of precious knowledge rasping through her puckered and hairy lips.

She might not have agreed with writing but at least she didn’t try to prevent me from doing it. I filled volumes as I followed her every movement, wrote down everything and sometimes made crude diagrams or drawings. We started with potions. At first, all I was permitted to do was fetch ingredients and occasionally stir the cauldron. Soon, however, I started to anticipate my mistress’ needs, bringing the reagents she required before she had asked for them, preparing them to the correct proportions and even suggesting subtle alterations in order to achieve a stronger or lengthier effect. Before long, she had left the preparation of potions, lotions, ointments and unguents, entirely in my hands, leaving her, she said, to worry about the more important work of curses, summonings and healings.

I was proud of the swiftness of my progress under Old Aggie’s unorthodox tutelage. I had mastered the creation of more than a dozen different potions in less time than it took my sister to master the art of eating with her mouth closed. But at the same time, I was unhappy that she seemed content to let me stagnate like a batch of unwanted hair-growth ointment slowly developing a crust in her cauldron.

“Show me how you summoned Monkey,” I demanded one day. “Not today, Maryk, not today. I am drained and you still have a quart of that eyesight potion to whip up. Perhaps if you come tomorrow, eh?” But tomorrow came and she was still too tired and besides she would always find another task to occupy me. I was still young by now, ten years old, but I was beginning to be able to sense things, perhaps in a similar way to father’s “feelings.” I was getting the feeling that Old Aggie feared me. She knew that, if she allowed it, she would quickly be surpassed by me and she was desperately afraid of that. If I wanted to learn any more from Aggie, I would have to do it by stealth.

So, stealing a few reagents from her macabre larder I decided to use Old Aggie’s knowledge against her. I had set up a tiny kitchen for the creation of my own potions in the attic space of our house on Saint Frackas Square. I knew that my sister would have no interest in invading this space and that Mrs Blanintzi was too frail to consider climbing the short but ill constructed ladder which connected it to the first floor. So, sneaking up to my cramped laboratory one autumn night long after everyone else was sound asleep, I brewed up a potion of invisibility. This was one of the recipes which I had learned from Aggie but which I had perfected through the accurate measurement of the ingredients and the obtaining of higher quality reagents than Aggie had ever used (I had estimated that Aggie was actually quite wealthy due to obsessive thriftiness and a general fear among the citizens of Pitch Springs that cheating a witch could have dire consequences.) Due to my improvements its effects lasted twice as long as Aggie’s recipe so I knew I would have at least thirty minutes, possibly up to forty, of total invisibility. It bothered me that there was such a margin for error and it gave me one of those feelings of my father’s when I thought about it.

I knew that this night she was planning on performing a summoning, much like last time when she she made a Monkey come out of her jar. She had asked me to prepare a few items she would need for the spell and to clear a space on the floor for her. Normally, she would not have allowed my presence at such a casting but on that night, she was not going to have the option to exclude me. Having brewed up my potion I tipped it into a little vial which I stored safely away in my satchel, wrapped in a rag. Then I wrapped myself up warm and set off to the edge of town and the Witch’s house. I arrived and waited outside until I heard the squawking of her bird. This usually meant she was beginning a spell. That’s when I necked the potion. I felt it tingle from my scalp to my big toes. It was as though I had grown a halo of super-fine hairs which extended out straight from my body in all directions, hiding me. It seemed also to heighten my senses of touch and vision. Once I was sure I was completely invisible I crept slowly, sure-footed, beneath the curtain which acted as Aggie’s front door, careful not to disturb it at all and then hunkered down in the corner by the doorway, holding my breath and watching the shit-daubed witch go about her witching business. I was not prepared for what I was about to be witness too.

Aggie stood there in the same blue excrement, over her large cauldron. I listened to her begin her low moan, slowly adding all the reagents I had set out earlier to the mixture. The fire was roaring below and every addition was met with a hiss. I made a mental note of the order in which she added all the items and then she picked up an item which I had not prepared for her earlier. It was one of the jar-bound homunculi, the tiniest of them which had a horn growing from its misshapen head and a tail as long as my little finger. She removed this thing from its confinement and held it two-handed above the cauldron. She ceased her moaning and spoke,

“On the body of this baby,

unborn and unloved,

I curse Jana’s child-bearing,

in the name of her husband,

and in your name Great Lord Shuggotz.”

and then dropped the body into the cauldron, the last ingredient. There was a plop and a hiss and gurgle and then a burst of sickeningly black and oily smoke from an enormous bubble which burst at the top of the mixture. the smoke dispersed about the hut and languidly circled until it escaped through the chimney hole.

I was shocked and disgusted. I was appalled that the woman with whom I had been spending so much time, the woman who was a teacher to me and who had encouraged me at the start, was a murderer, an assassin. I knew the couple she mentioned in her spell. Jana was heavily pregnant and infectiously happy with it but her husband was a layabout and a ne’erdowell. He would not want another mouth to feed. I had underestimated the depth of the man’s depravity, it seems. I wondered what he must have paid or promised Aggie for this service. It didn’t matter, I realised. I couldn’t kneel there on the hut’s dirt floor and allow this to continue any further. I had to act before Aggie finished her ritual and the curse was complete. I crept, still invisible, but more conscious than ever of the tracks I would be leaving on the dusty floor. I stayed low and moved directly towards the cauldron. Praying to Saint Volga, patron saint of alchemists that my potion would last long enough for me to perform my sabotage and escape, I took the rag I had wrapped my vial in and tied my right hand in it. Then I pushed on the underside of the cauldron. The rag was thin and did not cover my hand completely, I scalded myself quite badly and lost my fingerprints on that hand but it was as nothing compared to the injuries I inflicted on my mistress. The contents of the cauldron poured over the floor and Old Aggie’s feet, she screamed in agony as the boiling liquid blistered her skin and worse, I suspect. But soon, the pain of her cooked feet would become lost in the searing agony as her hut burned down around her. It might be truer to say it exploded around her. I watched as a few drops of the, as it turns out, highly flammable liquid splattered into the fire. It suddenly grew to twice its previous size and began to spread through the witch’s dangerously overfilled home, blowing up jars of volatile substances as it did so. I ran, and just as I did, my potion wore off. “Maryk! You killed me! I curse you! I curse you! I curse you!” cried Old Aggie as I slid under the burning curtain and ran home, never looking back.

So, there you have it, accursed twice by the age of ten. Not to mention the fact that I had murdered yet again. Greysteel did not count as murder perhaps, except to my father. Still, I imagined I had done a good thing by disrupting the witch’s spell. Perhaps one day, Jana’s child would do some great good in the world and my actions would be vindicated. Such were the arguments corkscrewing my mind in the nighttime for months afterwards. I have never slept soundly since that night, though the thoughts which occupied my consciousness naturally changed, their effects did not. These days I don’t sleep at all, not really.