Japanese Series

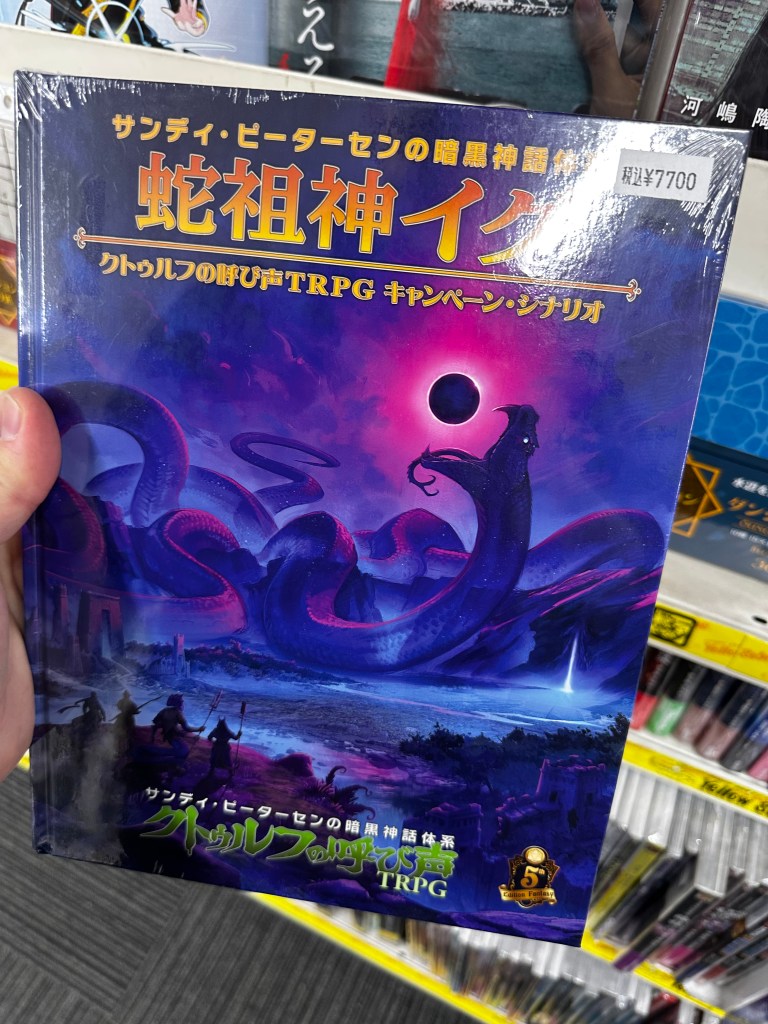

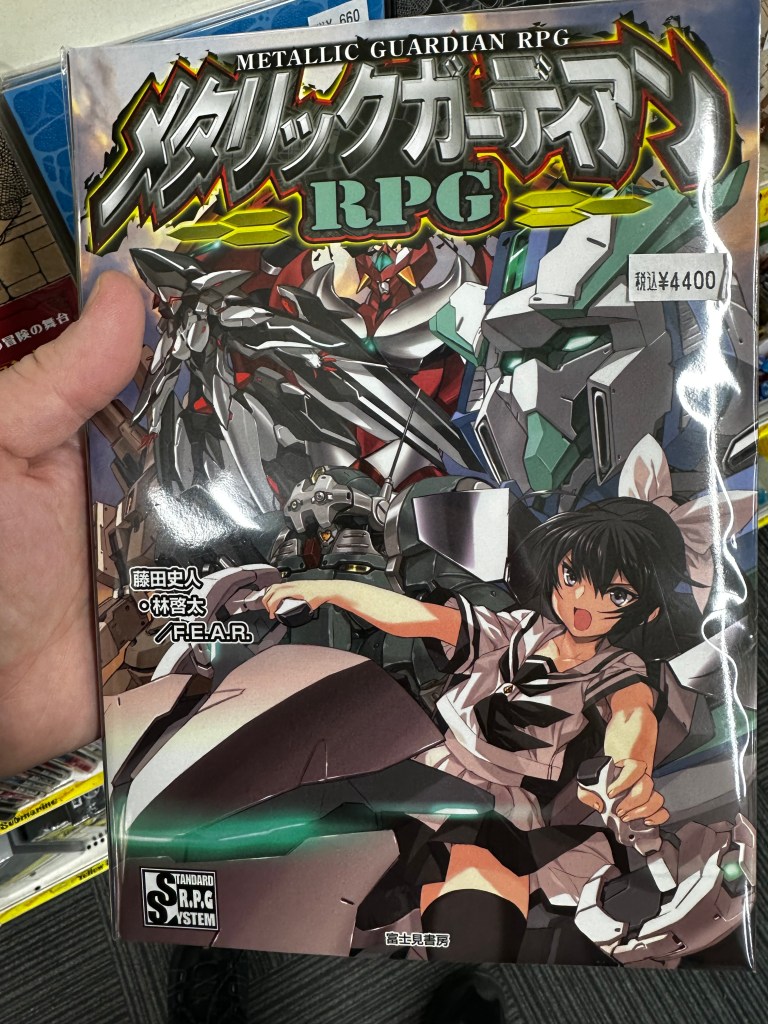

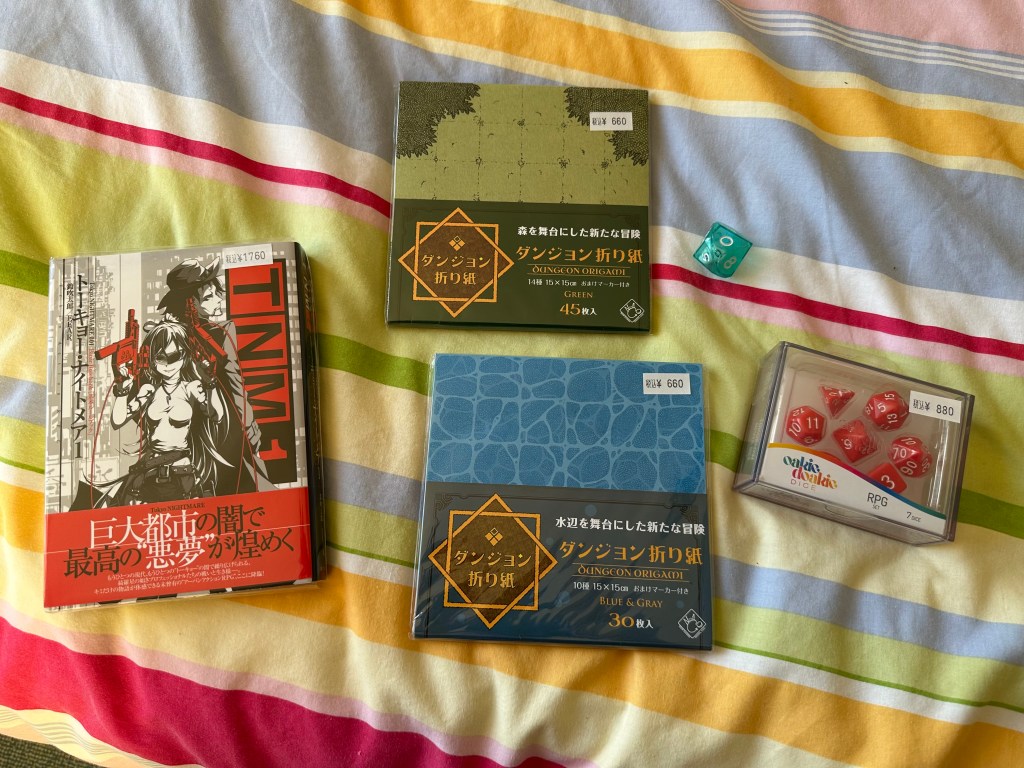

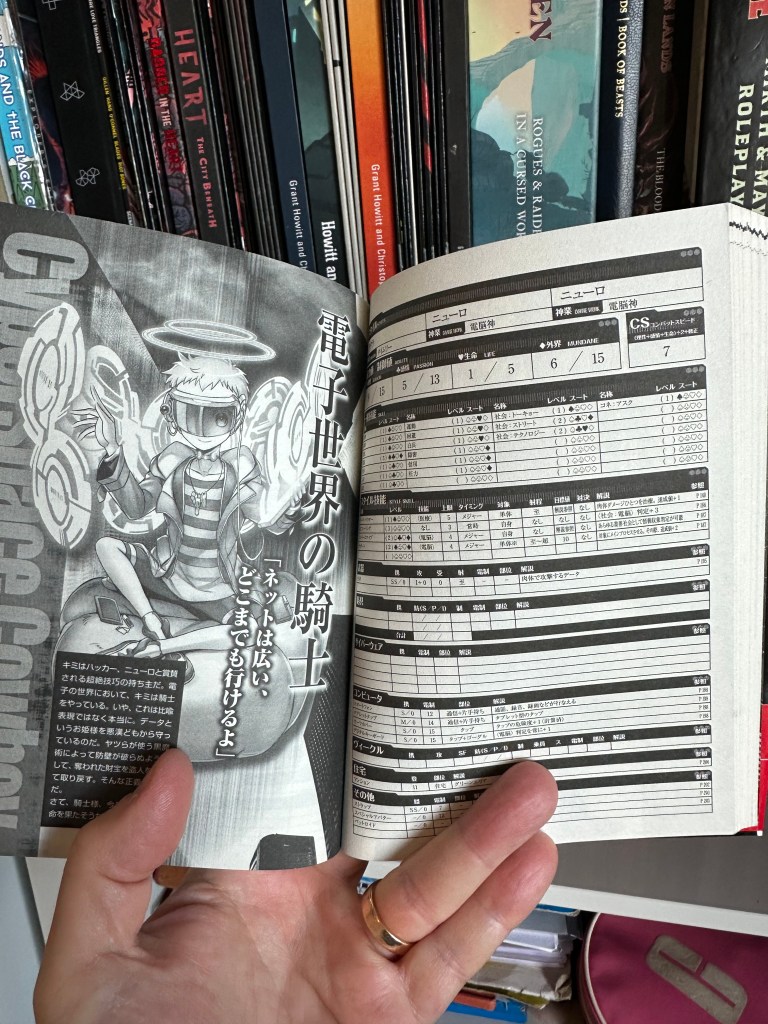

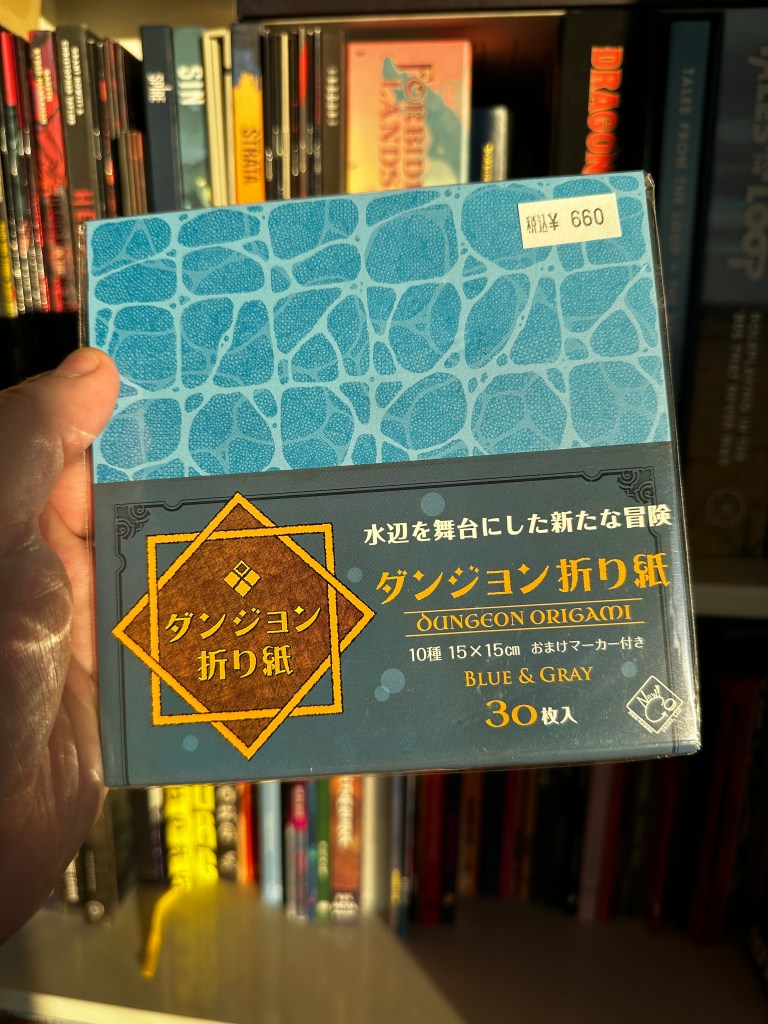

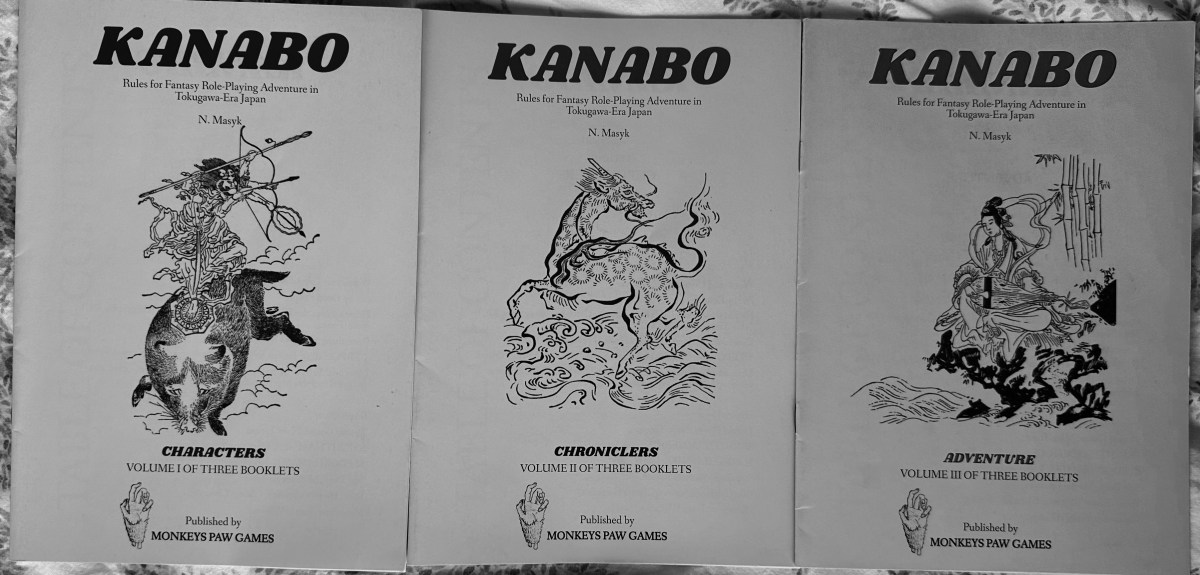

It looks like I have stumbled into a Japan-related games series, what with my recent posts about Kanabo and my visit to a Japanese Friendly Local Game Store in Fukuoka during my recent holiday. Combine it with a couple of posts on Call of Cthulhu in the last couple of months and this one fits right in.

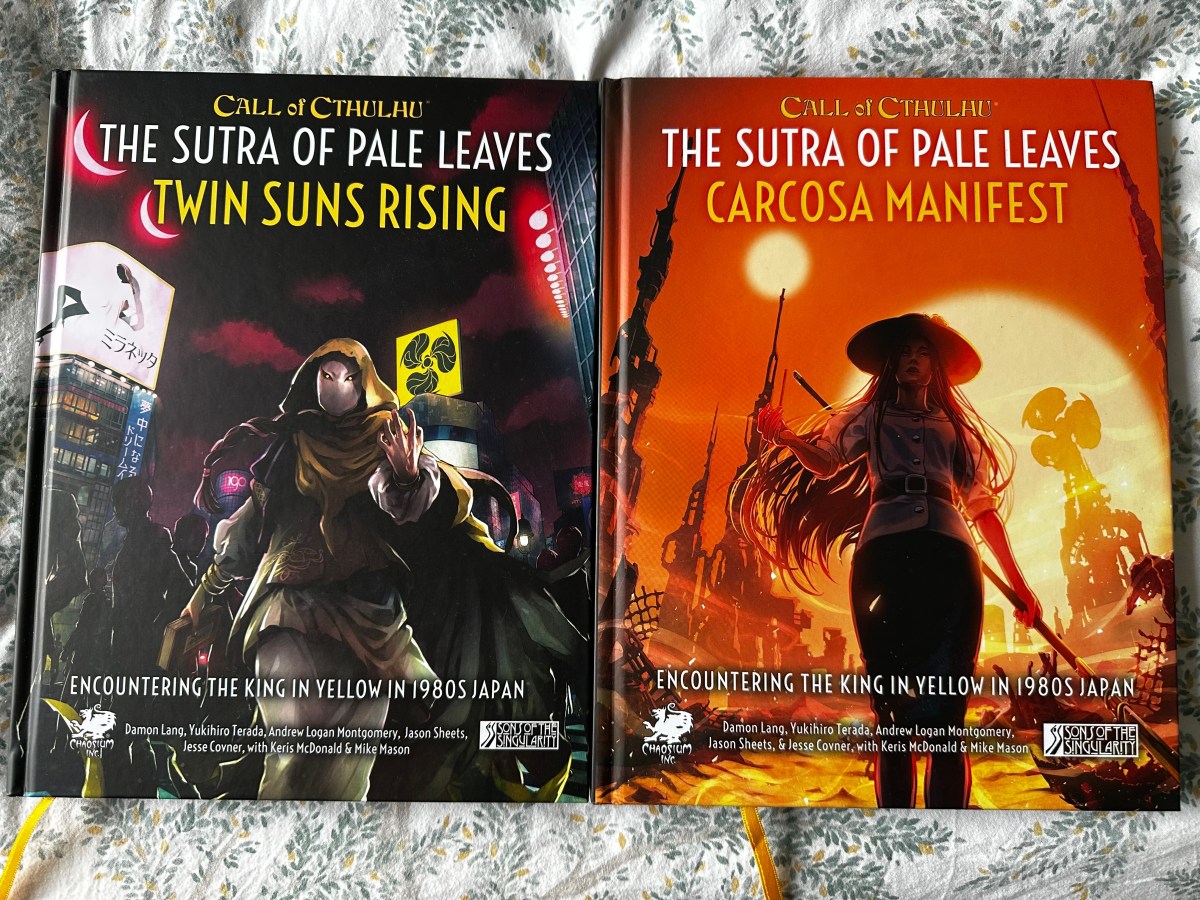

The Sutra of Pale Leaves

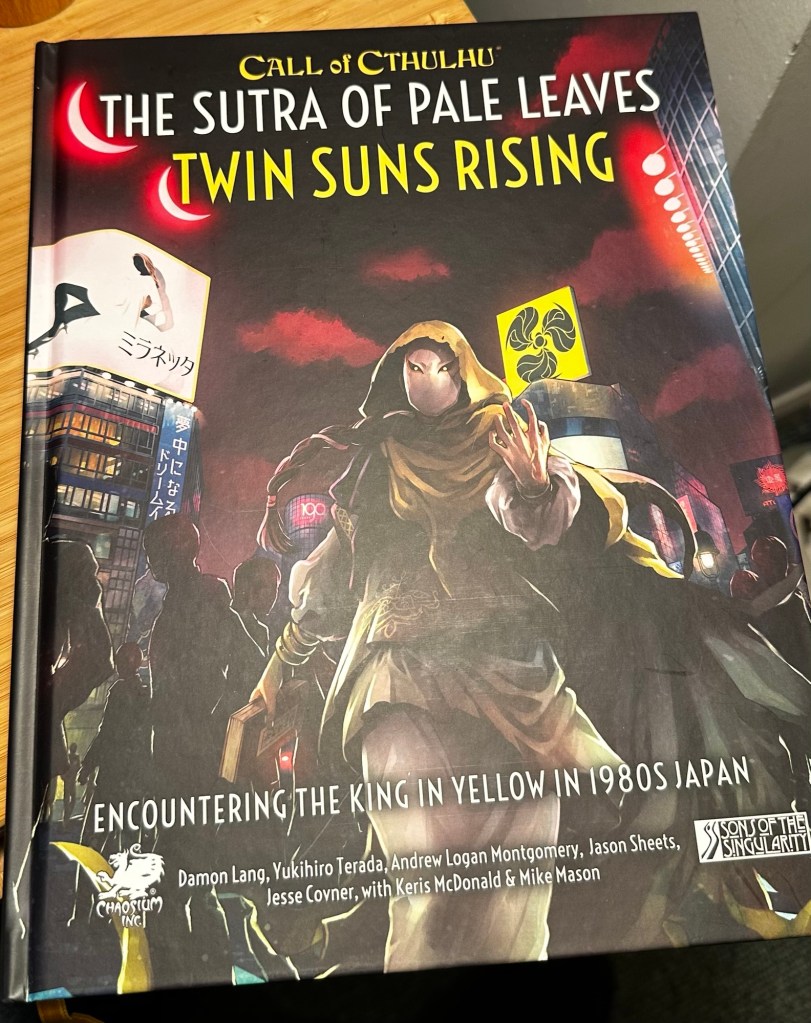

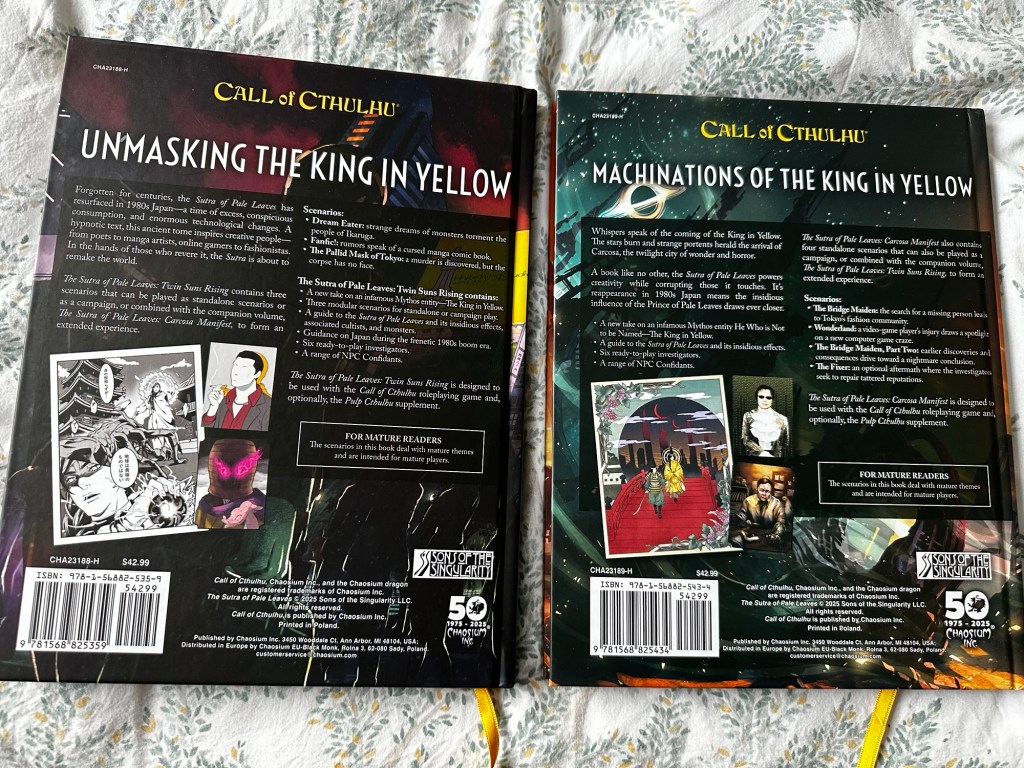

The Sutra of Pale Leaves is a 1980s campaign for Call of Cthulhu set in Japan, which is presented in the two books, Twin Suns Rising and Carcosa Manifest. Both were published by Chaosium in 2025. They have a number of main authors, Damon Lang, Yukihiro Terada, Andrew Logan Montgomery, Jason Sheets, and Jesse Covner for Sons of the Singularity LLC. Its good to see at least one Japanese name in there. The fact is, although there is just the one Japanese person credited in the main credits, there are other Japanese contributors in many other aspects of the production of this campaign, from artists to cultural consultants. A particualarly stand-out section of the credits is in the playtesters, where most of them are Japanese. I don’t think this project could even have the potential to reach any level of authenticity in the setting without all of that input from native Japanese.

What I’d like to do with this, and coming posts is take a look at the two books and see what they offer in terms of a campaign, how it might scratch an itch to play in a Japanese setting and how it might be used at the table. Needless to say, I have not run this or any part of it yet, though I fully intend to, once I find a bit of time. Still, I will be delving occasionally into SPOILER territory so, if you want to be a player in the Sutra of Pale Leaves, maybe give the next couple of posts a miss.

The Premise

The investigators are residents of Japan in the economic bubble-period of the 1980s. They are not necessarily Japanese, but, at least, have a passable fluency in the language. Through the events of the scenarios in the two books, they will uncover the some truths about, and perhaps even work to counter the goals of the Prince of Pale Leaves. Who, you ask, dear reader, is the Prince of Pale Leaves? Well, perhaps you know him by his more Western appellation, the King in Yellow? The Prince is the re-imagining of the being known as Hastur in Robert W Chambers’ King in Yellow stories, in a Japanese context. Although I have long been aware of those stories, I have only become more familiar with them through the work of Harlan Guthrie on the Malevolent podcast. If you’re unfamiliar, you could do worse than checking that out. It is a pretty different take on the King in Yellow, itself, but it’s a really entertaining one. If you fancy, you can get the book for free from Project Gutenberg, here. Otherwise, here’s a link to the Wikipedia entry. Essentially, the title refers to a play, which links the first four stories in the collection. The reading and performance of this play leads to it spreading like some sort of memetic virus. In the campaign, the eponymous Sutra of Pale Leaves plays the same role as that play.

There are a couple of interesting points made in the introduction section of the books.

First, they describe it as a modular campaign, meaning you can run each of the scenarios as presented, chronologically from July 1986 to November 1990 across both books. Or, you can run them in any order. There is not even a need to run all of them if you don’t want to and it is not a requirement to retain the same investigators through the scenarios, if you don’t want. Not having read all the scenarios yet, I can’t really say how will this would work, or how it would work at all. That’ll be one of the things I assess as I go through them.

Second, the nature of the Prince of Pale Leaves as an “ever-evolving antagonist” that exists outside reality as we know it gives him “the ability to metagame.“ What does this mean? Well, within the fiction, it means that he can take part in and observe the events of infinite branching timelines and use this ability to respond to events with preternatural knowledge, as though he knows what’s about to happen. In game terms, it means that if you replay the Sutra of Pale Leaves with the same players, or maybe just some of the same players, you can play him as if he knows what happened in the last playthrough… Which is wild. For the Keeper to use this ability might seem incredibly unfair to the players, who might accuse them of cheating. In that instance, the Keeper is encouraged to “show them this page of the book, and then laugh maniacally (!)” I love this but, as someone who has a chronic problem of trying to fit in too many new games into his schedule, the idea of replaying one feels almost ridiculous. So, I can’t imagine taking advantage of this particular little trick.

Japan

Both books begin with a bit of an intro to the place and time. Japan in the 1980s was a very special place. The country was rich and society was transformed by the money flowing into and around its cities and towns. It was the culmination of the post-war rebuilding of a country that had been utterly decimated. The Campaign Background chapter goes into just enough detail on everything from pagers and phones to organised crime. It gives you a glimpse into the everyday life of working people and students, enumerates some of the most popular pop culture of the period and even gives a short introduction to the pronunciation of Japanese words. Interestingly, it goes to some lengths to explain how this is a non-violent society where guns are nigh-on impossible to get your hands on, swords and other such weapons are just as prohibited and ninjas are just not a thing. This all serves to reinforce the idea that PCs are, perhaps, better off pursuing solutions that don’t involve direct conflict throughout.

The Sutra and the Prince

Since ancient times, there has been a cultural belief in Japan called kotodama (言霊, literally the “spirit of words”), a belief that mystical power dwells in words and names, and expressing them can influence the environment, body, mind, and soul.

And that’s the essence of the Sutra of Pale Leaves. The Campaign Background chapter continues with a description of what, exactly, it is, though. It also tells us how it works and the effects it has on people. Suffice it to say here that it is a text that has been around for centuries in many forms and which has travelled from beginnings in ancient India, only to be largely purged in Japan in the 12th century before re-emerging during the events of this campaign. It has the ability to quite literally imprint the personality of the Prince of Pale Leaves onto those who read it. In a mechanical sense, this is achieved through the accumulation of EP, Exposure Points. The Keeper is encouraged to keep the exact nature of EP from the players, perhaps referring to them as “Ethereal Power” or “Energy Points” instead. The default situation, however, has the Keeper tracking the EP for each investigator themselves, at least until it becomes obvious what effects they are having.

Of course, the more your Investigator reads, the more EP they gain and the more EP they gain, the more influence the Prince has over them. They might be subject, at the lowest levels of exposure, to convincing hallucinations brought on by their nascent Pale Personality. At the very highest level, 100, they are fully consumed by the Prince. “Game. Over.”

This is an extra, and fairly central mechanic to this campaign that seems like it could really add a lot in play. As one highly exposed character begins to betray signs of full domination by their hitch-hiker personality, others with less exposure, who are just beginning to see and hear things that aren’t there, might begin to fear for their own selves. There’s potential drama alright.

This section takes some time to usefully describe how each of the effects might manifest in characters and how these should be role-played (essentially meaning how should the Prince be role-played.) It also explains that there are some benefits to the exposed PC, such as “unexplained luck” and a “sanity safeguard.” With any luck, when the Keeper starts handing out freebies like these to exposed investigators, it should put the players on their guard, perhaps even making them paranoid about the motive behind such unexpected generosity.

The Prince of Pale Leaves himself gets a long section all to himself, as is appropriate given his central role in the campaign.

The Prince manifests as a viral artificial intelligence implanted in the minds of humans by full exposure to the effects of the Sutra of Pale Leaves. After exposure to the majority of the Sutra of Pale Leaves or its various adaptations, a portion of the victim’s brain is forcibly partitioned and systematically reprogrammed. From three individual hosts a network is born, and each one acts as a node for the singular mind that is the Prince.

Throughout this chapter the Sutra is referred to in terms of a computer programme or virus, the results of which are the over-writing of human minds with the software that is the Prince. I can see how this is a useful analogy but it seems like an odd one for this time. In a campaign set in the modern day, such comparisons might make more sense, but in terms of the 1980s, there was little or no general knowledge among the public of computer viruses or even networks. Still, it works to impart the concepts of both Sutra and Prince to a modern reader, and I suppose that is what’s most important.

The Cult and the Confidants

There is a very useful section on Roleplaying as the Prince, which gives some great tips on how to present him to various types of characters. He will deal with religious people by appealing to their faith while using reason and logic to appeal to skeptics, for instance. He is described as a “complex antagonist” and that certainly seems to be the case. Roleplaying NPCs like this is always a real challenge for GMs, since the Prince is a cosmic being with vast knowledge across multiple realities and timelines, but I, to put it bluntly, am just a pleb. So, any and all assistance is gratefully accepted.

In this section, we also have his powers, abilities and weaknesses enumerated. Finally, there is “the unspeakable truth” behind this being, where he “is,” what his physical existence looks like and what might be the answer to how he became this way. Importantly, it is revealed here that “patient zero” is sealed along with the rest of the population beneath Lake Hali in Carcosa, a world separate from our own, but one which is surprisingly close…

The rest of the Campaign Background chapter is used to introduce us to the obligatory cult, the Association of Pale Leaves and the most influential NPCs of the campaign. The Association is presented quite comprehensively with sections relating to their goals and doctrine, structure, and inner circle. There is also a very handy Cult Worksheet on one page for the times when you need a quick reference.

As for other NPCs, several are described under the section, Confidants: Plot Hook Facilitators. These NPCs, such as Mizutani Shogo, an intelligence agent, and Murakami Tsubasa, the abbot of the Kuroishi-ji temple, can be used to link one scenario to the next, to provide information to investigators to help them connect the dots and to assist them in regaining sanity between scenarios. The description of each gives you a few lines on the flavour of campaign they might add to, the sorts of connections they might have with investigators, where you might encounter them and the best scenarios they might act as confidants for.

Conclusion

It feels too soon for a conclusion, to be honest. I expect there to be at least two more posts about these campaign books. In the next post, I’ll be looking at the three scenarios in Twin Suns Rising. I’m really looking forward to sinking my teeth into them. Metaphorically, of course.