My Own Advice

In my post on beginnings I suggested a few things. It’s a good idea to start in media res. Starting in the middle helps to introduce the world to your players and helps them to introduce their characters to the world, assuming you give them enough narrative freedom to do so. I suggested using flashbacks to fill in blanks as necessary. But I also suggested that, for a longer game, you might want to begin with some in-depth scenes of the PCs’ personal lives to give everyone a good idea of what drives them.

So, how does this hold up to the advice provided by John Harper in Blades in the Dark?

Starting the Game

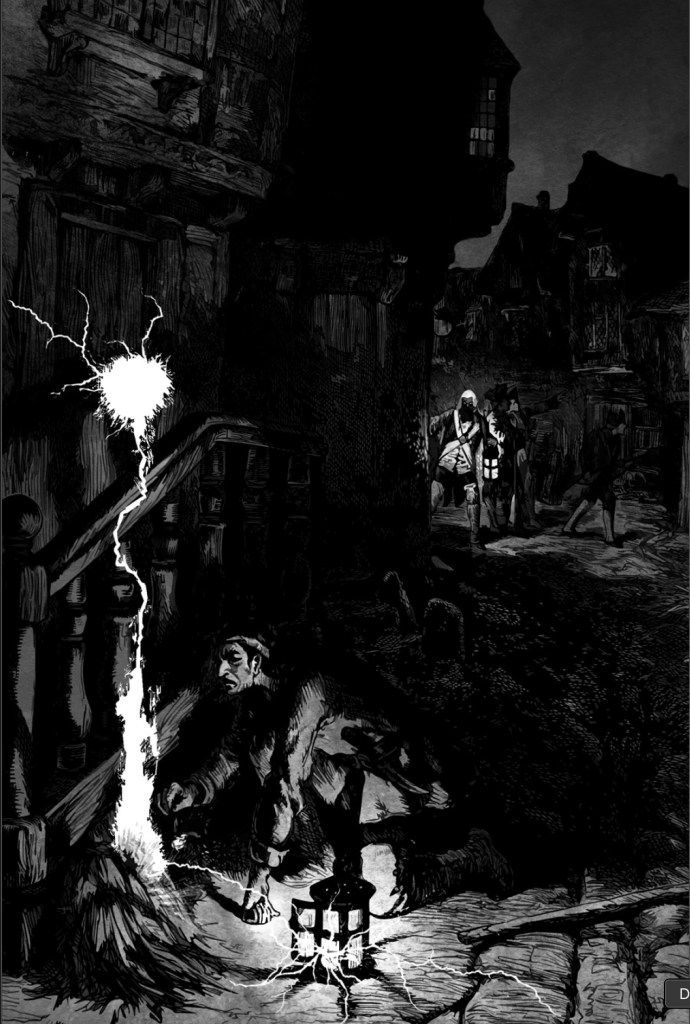

That’s the name of the section under the Running the Game chapter in the book. No confusion. I want to start by acknowledging that I think this entire section is fantastic. It’s full of gold. The advice presented here is the kind of thing I would love to see in every game. It was definitely the kind of thing I wanted from Spire before beginning it. I was so anxious about starting that game because I really was flying by the seat of my pants. Why? Well, because I had never played anything like it before. And in Blades in the Dark, Harper is perfectly aware that you’ve probably never played anything like this game before. So he takes your little hand and leads you gently into Duskwall, nodding reassuringly and telling you it’ll be alright.

Preparing for the First Session

Under the sub-heading, Preparing for the First Session, you get the advice to read through the character and crew creation sections again, assuming, I suppose, that you read them already. Here, it’s recognised that the GM is going to be the one leading on this and advising the players on how to create those scoundrels they’ve got in mind. Of course, this is good advice for any GM-led game but it’s good to have it in black and white here. Related to this is the fact that during these processes, the players are going to need answers about certain factions that will be relevant to their characters and the starting state of the city. So, you’re advised to pick a few factions you’re interested in or brush up on the ones mentioned in the starting situation, “War in Crow’s Foot.” To add to this, personally, I think you want to brush up on some of the factions, personalities and organisations that affect the entire city, like the Bluecoats, the Sparkwrights and the Spirit Wardens. You don’t need an exhaustive knowledge, but the basics will be helpful to allow you to answer some world-building questions, even if they’re not directly related to their characters or crew.

Harper states here that you should get through character and crew creation and, at least start the first score in your first session. This sets an expectation and, trusting that he has play-tested this a lot, its one that you have to assume is realistic. I also like the idea of taking these freshly minted scoundrels and throwing them straight into the action. I guess my in media res advice remains solid here.

There’s a short paragraph about what you can do to get yourself in the dark industrial fantasy mood of the game. Watch some Peaky Blinders, play some Dishonoured or read some Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser. I like this idea and it is something I do regularly to get me thinking the right way for an upcoming game with a very specific vibe.

Lastly, print out the character sheets and other reference sheets and get the gang together.

The First Session

The next section is entitled, “At the First Session: Setting Expectations.” This is always important. There are some formalised techniques to achieve this, of course. One of these is C.A.T.S. (Concept, Aim, Tone, Subject matter.) You can describe the type of game you’re going to play using CATS and, hopefully, that should help potential players to decide if they want to play it or not. Honestly, by the time you gather at the table, players should already be familiar with this stuff and know what to expect from your game. So this is not really what Harper is trying to achieve here. Instead, he’s trying to get you into, as he calls it, “let’s play mode.” He suggests a “punchy synopsis of the game” like this:

Okay, so you’re all daring scoundrels on the haunted streets of Duskwall, seeking your fortunes in the criminal underworld.

This is something I also love to do when starting a new game. I often take the blurb from the back of a book, or the summary from the first page and read it aloud, or paraphrase it to get the players in the right frame of mind so I would go further and remind them about what sort of dark, broken, victorian world this is, what the stakes are and the types of things they might be called upon to do.

Then continue:

Let’s make some characters and form a crew! Here are the playbooks. They’re the different types of scoundrels you can play. I’ll summarize them and then you can choose…

Harper goes on that the advise you to keep your explanations and rules-talk to a minimum at this stage. Introduce the players to concepts and answer questions but don’t get lost in the darkened alleys of Doskvol just yet. Instead, give a loose outline of the various playbooks and crew types, just enough to pique your players’ interests while they look through the options.

He then suggests saying something more like a sales-pitch at this point. The speech he includes in the book is real hearts-and-minds stuff,

This is a game, but it’s also something else—something really cool and unique. We’re gonna collaboratively create fiction together, by having a conversation about these characters and situations, without anyone having to plan it out or create a plot ahead of time. It’s like our very own TV series that we produce but we also get to watch it as a viewer and be surprised by what happens. You’ll say what your characters care about and what they do, and I’ll say how the world responds and just like that, a story will happen. It’s crazy. And fun.

I like this but I think I’d definitely come up with my own spiel. It’s just not me. I would definitely use this though:

play your character like you’re driving a stolen car.

Creating Characters and Crew

While the players work on their PCs, this section provides a set of questions to ask them. The text here does not suggest you ask all of the questions or that you ask everyone the same questions, or even that they should answer them out loud. Although I think I would try to get answers for at least a few of these to help me in making decisions as the game builds.

Here is a selection:

- Why did you become a scoundrel?

- The two of you have the same heritage. Do you want to be blood relatives? Do you know each other’s families?

- When was the last time you used your blade? Why?

- Who do you trust the most on the crew? Who do you trust the least? What’s that about? Or will we find out in play?

Harper points out here that we don’t need or really want to know everything about the characters before starting. A lot of the fun of playing a character is discovering them as you play, of course. The dynamic nature of Blades in the Dark and the degree of influence PCs can have over the world and, more importantly, the story, makes this particularly true of this game, from my experience.

You want the players to want to play their characters and to be excited about it. So Harper asks you to make sure, if anyone is not that enthused or is maybe frustrated by the process or any lack of detail that you spend a little time getting to the bottom of their dissatisfaction, providing more info if they need it, until they’re happy. You can also remind them that, if any of them find, after a few sessions that they wished they’d made a different choice here or there in character creation, then they can make the change, “no big deal.” An enlightened and realistic approach, I think, to what is, after all, just a game.

Once they reach the crew creation stage, they’ll have questions for you about the factions I mentioned earlier.

who gave them their hunting grounds, who helped with their upgrades, and who’s connected to their contact.

So, you’ll be happy at this point that you did that reading earlier. The advice here is, again, to use the factions in the starting situation to save yourself some work and associate the crew with the occurrences. This section ties things up by suggesting you skip crew creation for a one-shot, allowing the crew to develop organically during play instead.

Introduce Characters & Crew

Finally, it comes to the point the players will have been waiting for. They get to show off their cool new guys, their wee scoundrels! You get to use this to ask each player a few more questions to help clarify things or to get them thinking about how their PC might develop in play.

Some good advice here on how they should come up with their crew name. Even though they just put in a lot of work on crew type, upgrades, special abilities etc, the name can be elusive. So Harper suggests they leave that until after their first score at least. A suitable moniker is likely to come out of that.

The Starting Situation

I love this bit the most. You could potentially run Blades in the Dark games over and over again for years, one campaign after another, and use this same formula for your starting situation, and it would never get old:

- Set two factions directly at odds, with opposing goals. They’re already in conflict when the game begins. Both factions are eager to recruit help, and to hurt anyone who helps their foe.

- Set a third faction poised to profit from this conflict or to be ruined by its continuation. This faction is eager to recruit help.

And that’s it. It’s not overly convoluted. Three factions and their goals shouldn’t be too much to burden the players with and there should be plenty of potential in the situation. “Keep

it simple at first—things will snowball from here.”

The main thing is to give them something to do right off the bat, rather than asking “more creative work” of them. Once again, I love this. This is the sort of advice I wanted when I first ran Spire. Instead, I think I left my players floundering right at the beginning, without a clear idea of what they should pursue straight away. We ended up really enjoying that campaign but it always involved an awful lot of talking about what they were going to do next, planning that thing and then changing minds and starting over. And I think that’s because it never recovered from that first session, and its lack of direction.

The Opening Scene

Now you get into the nitty-gritty. This is practical advice that I really wanted. What should that first scene look like? What should you give the players here? What kind of thing is being asked of them? What if they don’t want the jobs that are being asked or demanded of them?

The most important lesson I am getting from this section is that the ball is in the PCs’ court. You need to give them a decision to make and they need to make it right now! Whatever happens, they are going into their very first score right away. No hanging about, no ifs, ands or buts. Love it.

Conclusion

The section ends with an example starting situation, “War in Crow’s Foot.” I’m not going to go into it because I might just use it. But I can tell you that its exactly what I’m looking for here. It’s a concrete example of the way the GM gets things started and how you can hand it over to the players. It’s got sample scores from different NPCs and advice on how to play those NPCs too.

Having read this whole section and followed some or all of its advice, you should be more than prepared for the crew’s first big score.

Discover more from The Dice Pool

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Beginnings in the Dark”