Formalising the informal

We introduce informal rules on the fly in our games all the time. You need to figure out if someone can find a newspaper stand around here somewhere? Sure: odds, you find one, evens, you’re out of luck. Oh, you rolled a nat 20 on your investigation check? Well, that means you also get advantage on your next Thieves’ Tools check. You know what I’m saying. It’s not unusual. So, is it unusual to formalise this informality? Maybe, I suppose. But that is exactly what Huffa has done in her new book, Between the Skies.

I heard about this game from the Yes Indie’d podcast from Thomas Manuel. On the episode I linked above, you can hear him interviewing the writer and creator of Between the Skies, Huffa. You can get most of the background of the game from the podcast, if you’re interested, but if you need a TLDR, it started off as a digital release and then a series of zines you could get on itch.io until Exalted Funeral got involved and made it into a book. You can still get those there in free PDF format, by the way.

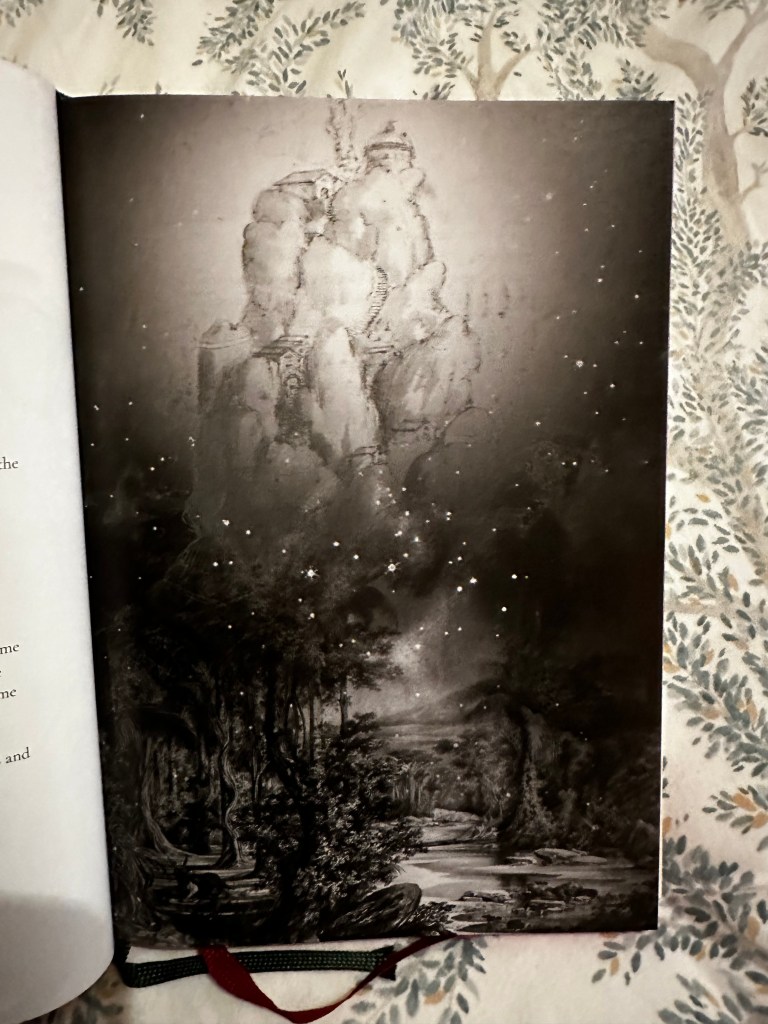

A couple of things struck me while listening to Huffa talk about her work. First was the subject matter of the game, which seemed rather Planescapey to me, the nineties one. Maybe cross that with some AD&D Spelljammer, a wee sprinkling of Troika! and just a little bit of Black Sword Hack. Strangeness in the spheres and across the planes of existence is the overall theme. It sounded both very old school and incredibly fresh at the same time. Where does the freshness come from, I hear you cry, dear reader! Well, that would be from the other thing that struck me about the interview; the ideas Huffa espouses when it comes to rules.

Why restrict yourself to one ruleset when there are so many out there to choose from?

So, like my very wordy sub-heading says, why go full Forged in the Dark all the time when certain situations might call for a Resistance System style roll with pre-established fallouts to hit them with? Why limit your game to using only Powered by the Apocalypse rules when you might also want to use adversity tokens sometimes? The point is, you should be able to play almost any game you want, using almost any rules that suit, not just the game but any given situation within a game. Is this dangerously anarchist? Maybe, but it also sounds like excellent fun. If you have been around here for a few months you’ll know that I like a good ludicrous mash-up. See my various attempts to introduce new and exciting elements to my D&D 5E game here and here. You might also remember me going on and on about how cool it was to use other games to establish the world and the city in a Blades in the Dark campaign I recently took part in.

If you’re interested in games and the rules of games and how they interact with the players, the setting, the events, this is an approach I think you might be able to appreciate.

Now, I will say that Huffa is not necessarily suggesting that you should abandon a single ruleset play style, but that you should open your mind to the idea of using the ruleset that most appeals to you when you pick up Between the Skies to play it.

Playtime is the name Huffa uses for the set of procedures presented in the book to allow for the style of play it espouses. It’s all about the “shared understanding of a fictional world.” And really, however you achieve that is the way to do it, with the understanding that this might look different for literally every table. Here are a couple of relevant quotes from the introduction:

“Judgement based on shared common sense is the fundamental ‘rule.’”

“All rules, methods and procedures can be used or ignored.”

This type of play is related to the FKR or Free Kriegspiel Revolution. This is a movement that rejects the cumbersome mechanics prevalent in so many games, particularly from the war-game or “Kriegspiel” side of the hobby. In FKR, the game is very much a conversation, where a player may suggest a way of overcoming an obstacle and the referee or someone in a similar role will make a judgement, based very much on the table’s shared understanding of the world they are creating together, as to whether or not it would work. Dice rolls may occur but they will be minimal.

And yet, Huffa has provided here, in the At Play Between the Skies chapter, a plethora of potential rules. Here’s a brief collection of some of the suggestions.

All time is tracked by Turns but the time scale of the Turn is dependent on the situation, longer for travel and exploration, shorter for investigation and shorter still for combat.

The Occurrences table on page 46 feels like the most basic denomination of the tables in this book. It is incredibly general but its presence and usage suggests at the way the whole game is to be played.

Use tokens to succeed at risky actions or extraordinary actions. Or! Choose a dice rolling mechanic from any of the bunch described in the book (coming from games like Blades in the Dark, Apocalypse World, Traveller, Electric Bastionland etc.) and see if you succeed, or if you succeed with consequences or if you just fail.

Or you can just play without dice!

Give your characters Conditions when they should get them. Let these conditions affect the riskiness of actions.

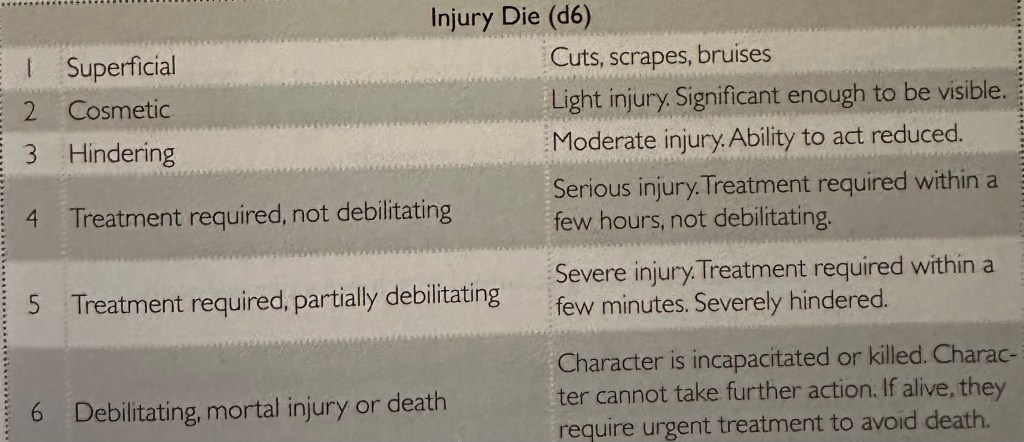

Injuries! Roll on the Injury table to really fuck them up. It’s a 1d6 table and the 6 is death or fatal wounds… So use this sparingly, I guess!

You can, as Huffa suggests, use all of these rules or none of them or you can add any other systems or subsystems you can think of where appropriate.

Approaches to Weirdness

In the Setting Up Your Worlds Chapter it is time to decide how strange you want this game to be.

“Between the Skies is filled with weirdness. Its tables, and its author, revel in the strange.”

Huffa provides some options here, broad categories of weirdness that will help to define exactly how weird things are likely to get. Of course, this might change during the course of play, depending on how you and your players get into it.

Go “All the Weird” for a setting and game where the characters are probably at home in a very strange and out-there place. The sky is not even the limit here.

With the “Venturing Out into the Weird” approach you play humans with a limited but very much real knowledge of other planes and spheres but who have never left their homes before. Everything will be new to them but high levels of weird are ok.

If you want to be the weird in everyone else’s world, take up the “Playing he Monsters” approach. Your characters will be the only magical, non-human, truly strange things in an otherwise normal world. You will probably be feared and hated.

In a “Through the Looking Glass” style game your characters will start the game having found themselves in a strange and magical new realm. But they themselves are relatively mundane and must figure things out as they go along.

The approach you decide on will also have an influence on the character creation method you use. So it is of primary importance to the type of game you are looking to play.

This section of the book asks a lot of questions about how the planes and space work in the universe of your game. There are familiar touchstones here with Planescape and Spelljammer being the obvious ones. But it tries to get you to really think about important things like how PCs might travel through this weird space, how gravity works and the real difference between worlds, space and the planes, if any.

Next time, I am going to get into the Between the Skies approach to character generation, which is exactly as lassaiz faire as you might have come to expect by now.

Discover more from The Dice Pool

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Between the Skies Part 1”